In the early morning of June 18, 2023, we woke up to find that the Monarch Queen had nearly completed its journey of 188 kilometers upriver from Budapest to Bratislava, the capital of the relatively new country of Slovakia. I took my camera onto the top deck to photograph our progress through the outskirts of the city as the ship made its way to the dock.

To get to Bratislava from Budapest, the Monarch Queen had to sail north to the great bend in the Danube near V

But as we entered the city limits, the river narrowed down and the banks closed in on us, bringing the urban architecture into clear view and giving me some good opportunities for telescopic shots with my 70-200mm zoom lens. I was able to photograph some of the attractions that we would see closer-up later in the day on our walking tour.

Bratislava sprawls on both sides of the Danube, with a number of beautiful bridges spanning the river to connect the two sides of the city. The Monarch Queen passed under several of them on the way to the dock: the Lužný, the Prístavný, the Apollo, the Starý and the Nový. Having gone below for breakfast, I missed the first three, but I did capture the last two, which are arguably the most interesting. The Starý Most, or Old Bridge, is not really old, having been completed in 2015, but it replaced a much older one which had been destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries. Traffic on it is restricted to pedestrians, cyclists and streetcars. Most striking is the Nový Most (New Bridge), which is not actually new, having been built in 1972. It was called “new” because it was only the second bridge built in Bratislava after the Old Bridge. But the official name is the Most SNP – for Slovenského národného povstania, which translates as “Slovak National Uprising.” It is an asymmetrical cable-stayed bridge, meaning that the span is suspended from cables attached to parallel towers at one end. It reminded me of the Alamillo Bridge in Seville, which we had seen in 2017, although the Alamillo only has one pylon instead of two. The Nový Most was somewhat controversial when it was built because a quarter of Bratislava’s Old Town, including most of the Jewish quarter, had to be demolished to make room for the roadway leading to it. The Nový Most carries motor traffic on its upper level and pedestrian and bicycle traffic on the lower level. At the top of the bridge’s dual pylon is a structure shaped like a flying saucer, which houses both an observation deck and a restaurant, called the UFO restaurant. It is highly rated for its cuisine as well as the panoramic view, but time did not allow us a chance to sample either.

The Monarch Queen docked right next to the Nový Most, on its north side. As it tied up I continued to shoot the sights of the city, mostly the north bank, where the old part of Bratislava is located. The newer segment of Bratislava, known as Petr

Shortly after docking, we began our walking tour of old Bratislava, starting with Rybn

This is a good place to mention a few things about the history of Bratislava. It has had a number of different names during its long history. During the Middle Ages it was in the Kingdom of Hungary, and the Hungarians called it Poszony. But the Germans, who constituted the largest part of the city’s population during much of that time, called it Pressburg, and that was its official name during the period of Austrian domination, from the 16th century onward. Following the defeat of Austria-Hungary in World War I, the city was taken away from the Kingdom of Hungary and given to the new state of Czechoslovakia, and that was when the name was finally changed to Bratislava.

Following the Munich Agreement of 1938, Germany marched into Czechoslovakia and dismembered it, occupying the Czech lands as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The Slovaks split off to form the Nazi puppet state of Slovakia, with Bratislava as its capital. After World War II, Czechoslovakia was re-established, but it broke up again in 1993 after the collapse of the Communist regime, with Bratislava again becoming the capital of Slovakia.

Prior to World War II Bratislava had a sizeable Jewish population of around 15,000, which of course was decimated during the war. Later, in the 1960s, much of the old Jewish quarter was demolished as well, including two of the three synagogues, one of which was a Neolog Moorish-style synagogue similar to the Great Synagogue in Budapest. Now about all that remains of it is a pile of rubble next to the Holocaust Memorial on the north part of Rybn

Just north of Rybn

From Rybn

Turning left at Vent

We were heading toward Michael’s Gate, Michalská brána in Slovakian; originally built around 1300, it is the sole surviving city gate from the medieval period. Actually it is not the original gate, because that was torn down in the 16th century and later rebuilt as a Baroque structure in 1758. But it is rather impressive. It is located at the end of Michalská Street, which is a continuation of Vent

At the corner of Vent

Looking down Prepoštká Street, which runs east and west, from the corner of Vent

From Michael’s Gate we went a short distance to Franciscan Square, so named because of its historic association with the Franciscan mendicant order of the Catholic Church. It is the location of the Church of the Annunciation, Kostol Zvestovania Pána, the oldest surviving religious building in Bratislava, consecrated in 1297, as well as two chapels and a Franciscan monastery. Across the street are a couple of art galleries, one of which occupies the Mirbach Palace, a splendid 18th-century Baroque/Rococo structure built by a Bratislava brewer and bequeathed to the city by its final private owner, Dr. Emil Mirbach.

Down the street from the Church of the Annunciation is the Church of the Holy Savior, better known as the Jesuit Church. This was originally built as a Protestant church in 1636-38. The date of construction is noteworthy in itself, since the Thirty Years’ War was in progress and the Habsburg monarchy was doing its best to erase Protestantism in all its dominions. Although the regime did not prohibit the construction of the church, it did decree that it could not resemblance to a Catholic church in any way, meaning no spire, presbytery or even an entrance on the main street. By 1672 the Habsburgs had succeeded in evicting the Protestants from the church and handing it over to the Jesuits, who have held onto it ever since.

Franciscan Square abuts the main square of Bratislava, which coincidentally is called Hlavn

The oldest part of the Old City Hall is the Tower, built around 1370. The Tower was part of a house built by the mayor, whose name was Jacob; hence it is known as the Jacob house. Next to it is the Pawer House, built in the 15th century. (The dates are a bit uncertain because the information available is somewhat vague and confusing.) Then comes the Unger townhouse, a former burgher’s house which now houses the city archive. Finally there is the Apponyi Palace, built in 1762 by Count György Apponyi and acquired by the city in 1867.

The Old Town Hall has a courtyard, into which our guide led us through a portal next to the Tower. The courtyard, as far as I can tell, was formed by joining three wings of the Pawer House to the Jacob house, which extends back from the Tower. But the Old Town Hall has been subject to so many repairs, reconstructions and modifications over the centuries that the courtyard does not present anything like its original appearance. There was a Renaissance reconstruction in 1599, a Baroque restyling in the 18th century, and a Neo-Renaissance/Neo-Gothic wing added in 1912. I found the courtyard quite attractive and pleasant. In one corner there is a bust of Franz Fl

Passing through another portal in the back of the courtyard, we found ourselves in Primate Square, the site of the Primate’s Palace. This is a neoclassical palace built from 1778 to 1781 for the Archbishop of Bratislava. Its famous Hall of Mirrors has been the scene of a number of historic events over its two and one-half centuries of existence; perhaps the most consequential was the signing of the Treaty of Pressburg on December 26, 1805. In early December Napoleon had inflicted a catastrophic defeat on a combined Austrian and Russian army at Austerlitz, perhaps the greatest victory of his career. The Austrian emperor, Franz II, was forced to sign a harsh peace with France, and the following year he abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor (though he compensated himself by assuming the title of Emperor of Austria as Franz I). His abdication put an end to the Holy Roman Empire, which had been around in one form or another for more than 800 years.

Returning to Main Square, we noticed on its west side, opposite the Old Town Hall, a trio of attractive structures. The rightmost one, the Palugya Palace, was built by a local wine merchant and reconstructed around 1880 in the French Baroque style. To its left is a seductive building in the Art Nouveau Secession-style which turned out to be the Palace of the Hungarian Discounting and Exchange Bank. (Art Nouveau Secession was a Viennese branch of Art Nouveau that flourished during the years 1892 to 1906; it was characterized by an organic style, typically with floral designs, in contrast to the more geometric expressions of regular art nouveau.) I wasn’t able to find out much about either of these two buildings, and nothing at all about the third (leftmost in the picture), which in my snapshots was partly obscured by the buildings on the south side of the square, where the embassies of Greece and Japan are housed.

In the middle of the square is a grand fountain, known as Maximilian’s Fountain or the Roland Fountain. It was erected by Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Hungary, in 1572, to provide a public water supply. The fountain is topped by a statue of a knight in full armor, which is said to to represent Maximilian as the hero Roland, who was a legendary defender of Bratislava.

On the north side of Main Square is the former Viceroy’s Palace, now a Slovak government office building. Next to it is the Kutschersfeld Palace, a rococo structure dating from 1762 which now houses the French Embassy. Out in front of the French Embassy is a plain wooden park bench, and behind the bench is a statue of a French soldier bent over with his elbows resting on the back of the bench, looking as if he were disposed to conduct conversations with people sitting on the bench. A local Bratislava legend has it that when Napoleon and his army came to Bratislava in December 1805, with 9,000 infantry soldiers and 300 horsemen marching through the streets, one of his soldiers fell in love with a local girl. The soldier, whose name was Hubert, decided to stay in Bratislava and began making sparkling wine which he named after himself. However, I like to think that the figure represented by the statue is not just a soldier but Napoleon himself. I photographed him in conversation with a couple from the Gate1 tour group, making extravagant claims about his victories and sorry excuses for his defeats.

At this point I need to mention that Bratislava is a city of statues, many of them quite whimsical. They are mostly of recent origin and are the result of an effort by the municipal government to create interesting landmarks that would soften the city’s supposedly stark and austere appearance as it emerged from a half-century of war and Communism. Although I didn’t find Bratislava austere, I did feel that the statues add a lot of charm to the place. We were to encounter more of them during our excursion.

Another local legend, told to me by our tour guide, was that the expression “Blue Danube” has nothing to do with the color of its water. She claimed that in one battle between the Austrians and the French fought near Pressburg, so many French soldiers were killed that they could not be buried, but had to be thrown into the river. Since they all wore blue uniforms, they colored the water blue, and that’s why it is known as the Blue Danube.

Leaving Main Square at its southwest corner, we encountered another statue, that of Schöner Náci. He was a local character of humble origin, born Ignác Lamár, the son of a shoemaker, and during his lifetime (1897-1967) took it upon himself to roam the streets of Bratislava, dressed in a top hat and coat tails, on a mission of greeting people and spreading joy. (One wonders how he escaped the attention of the Communist authorities, who were generally dedicated to doing the opposite.) He is now long gone, but his memory is revered in Bratislava.

Proceeding south along Ryb

From

The Slovak National Theater was built as the City Theater in the 1880s to hold 1,000 spectators. In front of it is the Ganymede Fountain, depicting the youth who was kidnapped by Zeus and flown by an eagle to Mount Olympus to become the cupbearer of the gods (and Zeus’ lover).

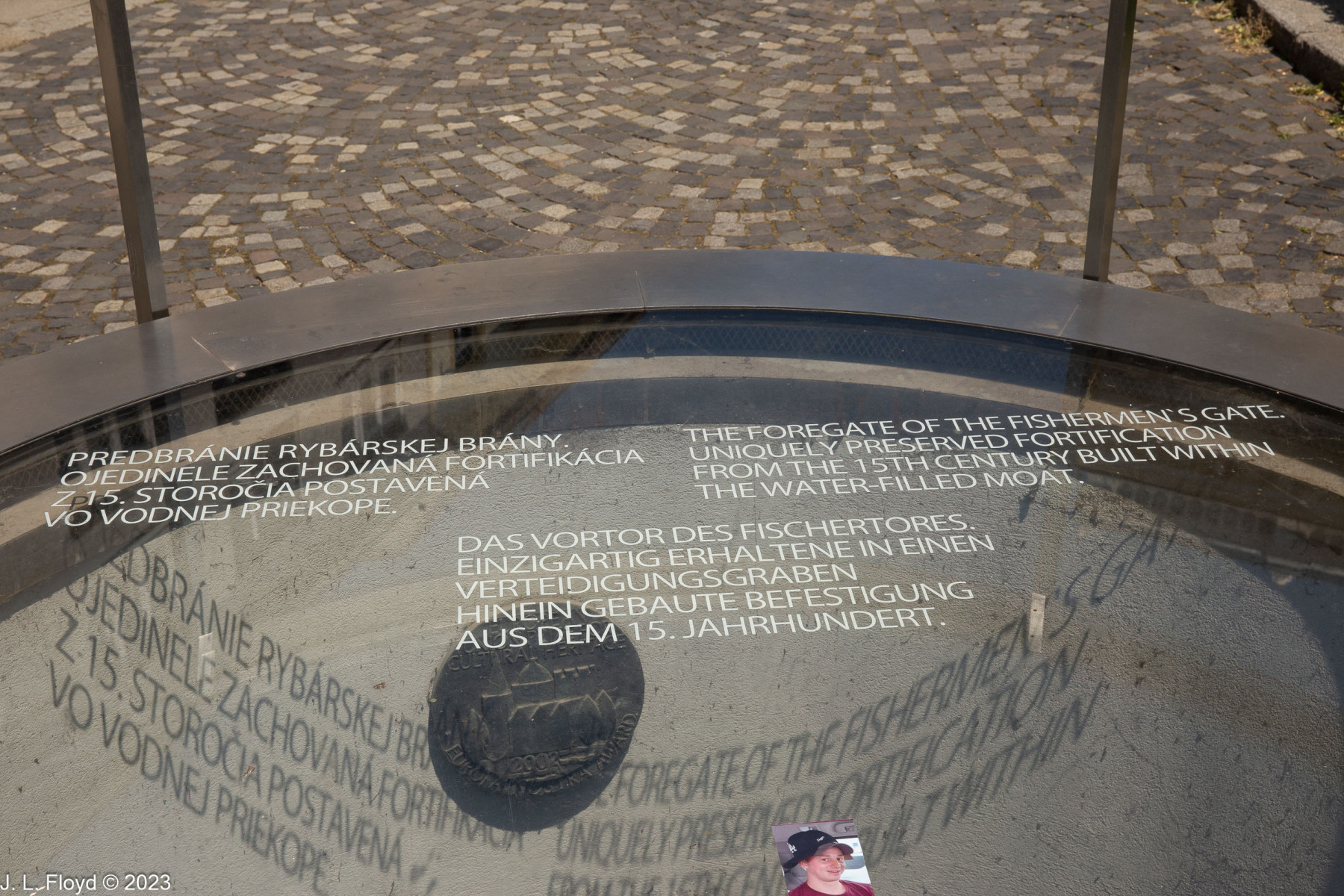

Also in front of the Theater there is a shaft, protected by a plexiglass dome, leading to an archaeological site unearthed during pavement repair at the end of the 20th century. This is the remains of the actual Rybárska brána gate, after which the street is named. Like the Michalská brána, the Rybárska was part of the city fortifications; it was the closest gate to the Danube, and the one through which fishermen brought their catch into the city, and ryba means “fish” in Slovakian (as in most Slavic languages, including Russian), hence Fishermen’s Gate. But during the Turkish wars, when the Ottoman Empire besieged Bratislava/Poszony, the gate was partially sealed up and access was reduced to a narrow passageway. It was restored in the 18th century, but in 1776 Empress Maria Theresa ordered it demolished again to make way for urban expansion.

The broad expanse where the Theater is located is called Hviezdoslav Square (Hviezdoslavovo námestie), named after the Slovak poet Pavel Országh Hviezdoslav (1849 – 1921). It is actually more of a promenade than a square, since it extends from the Slovak National Theater all the way down to Rybn

That evening, on the boat, our tour director Krysztina regaled us with tales of life in Eastern Europe under Communism. She was born in 1976, so she had experienced it first-hand. Since I myself had lived in the Soviet Union before she was born, in 1972-73, nothing she said surprised me: the continual shortages, the restrictions on personal freedom, the generally drab and dismal atmosphere – all of that was familiar. She noted that in the 1970s Hungary underwent some liberalization, known as “goulash Communism,” and life got better – the Hungarians started getting bananas from Cuba. East Germans started coming to Hungary on vacation because life there was better than in the GDR. Hungarians themselves were allowed to travel abroad every three years but were only allowed to take 50 euros with them, which rather limited their tour options. The educational system was very restricted; only a few people were allowed to learn languages other than Russian. Krysztina herself started learning German at age 8 (that would have been 1984). (English was her second language, and she speaks it idiomatically, with only a slight accent.) She also mentioned that after the collapse of Communism, although life in general improved, it was the former Communists who prospered most; many older people, especially those of proletarian background, did not have the education or the connections to compete successfully. Of course the same was true in Russia.

The same night the Monarch Queen sailed for Vienna, which is a scant 80 km (50 miles) by car, probably less by boat, from Bratislava. I had not yet been to Vienna, and I awaited the arrival with much anticipation.