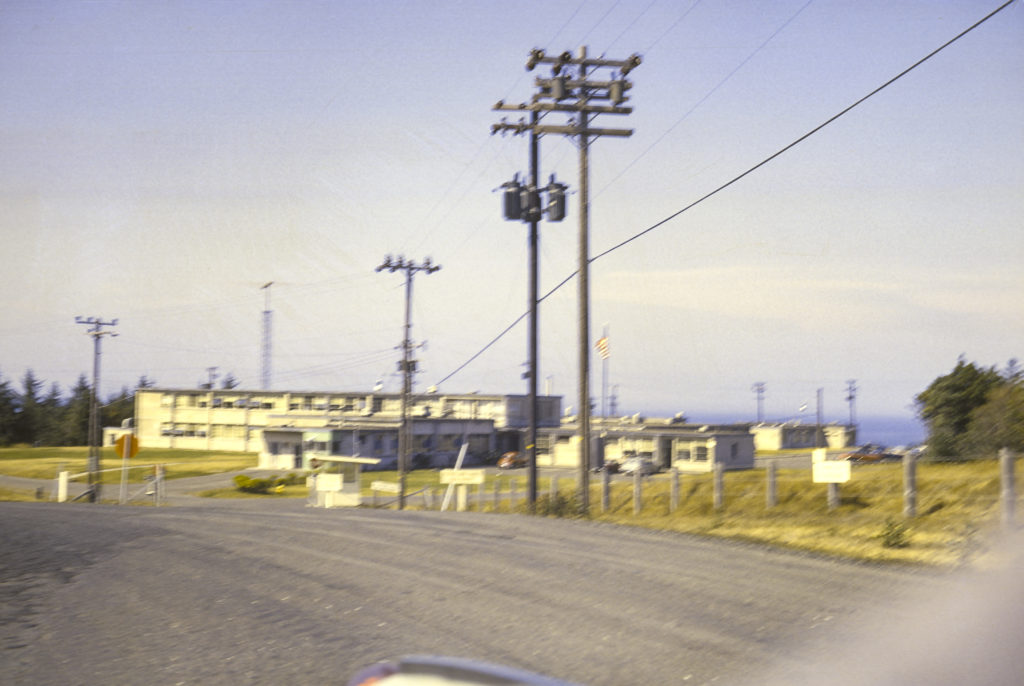

My first duty assignment in the Navy (other than training) was to the U. S. Naval Facility Centerville Beach, near Ferndale, California. The Naval Facility (NAVFAC) was part of the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), which consisted of a series of small stations located up and down the east and west coasts of the United States, as well as certain strategically located islands in the Caribbean and elsewhere, including Adak in the Aleutians and Iceland in the Atlantic. The mission of SOSUS was to detect and locate Soviet submarines. More on that later.

Ferndale is a town in Humboldt County about 20 miles south of Eureka, situated near the mouth of the Eel River, about five miles from the shore of the Pacific Ocean. The population is around 1370 and hasn’t changed much since I was there in the ’60s. Another nearby town, much larger than Ferndale and about five miles from it, is Fortuna, situated along Highway 101. I arrived at NAVFAC Centerville Beach in early April, 1965, a few months after the Eel River flooded the area and cut Ferndale and the Naval Facility off from the outside world for a period of several weeks. By the time I arrived, the flood waters had receded, but the residue of the disaster was all too visible – washed-out roads and bridges, bare flood-swept desolation, debris all around. The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Commander Richard Dickson, was a kindly fellow, a nice guy who was on his way out of the Navy and did, indeed, retire a few months after my arrival. His Executive Officer, Lieutenant Skip Sedlak, wasn’t such a nice guy. He was an ex-submariner, which was fine; the trouble was that he was also a boorish, ignorant imbecile. He was single because his former wife couldn’t stand him, which was understandable, since nobody else could either; and he was a fanatical 300% American who saw a Commie under every bunk. He was also a bit of a sadist, but I’ll get to that later. My transportation at the time was a 1965 Triumph Spitfire, a two-seater sports car, which I had bought upon graduation from Naval OCS. Additionally, when I first reported for duty at the Facility and was making the XO’s acquaintance, I happened to mention that I had ridden a motorcycle before I was in the Navy. Skip’s comment on that was “Oh, the CO won’t like that. He hates sports cars and motorcycles.” Skip enforced the CO’s prejudices with gusto, and generally enjoyed making life miserable for as many people as possible.

For his part, besides disliking sports cars and motorcycles, the CO had other quirks. A couple of months before my arrival, when the floodwaters had cut off the Facility from the outside world and no supplies were getting in, the mission of the Facility was threatened, and the Navy doesn’t like excuses such as “well, we couldn’t perform our mission because we ran out of supplies and none of our equipment would work.” The CO got so frustrated at the obstacles that he kicked in a metal cabinet in front of the men, which is not considered “coolness under fire” in the Navy. His most notorious idiosyncrasy, though, was his prudishness. Although he had an extremely attractive Japanese wife, he had an odd attitude toward sexual issues. Many enlisted men in the Navy liked to keep pinups from Playboy in their lockers. LCDR Dickson prohibited these, and when he conducted inspections of the barracks, he would check the men’s lockers for pictures of naked or scantily clad women, and remove any he found. I was also told by people who had served with him previously, of whom there were several on the base, that when serving on shipboard as the Executive Officer of a destroyer, whenever he found a Playboy or other such publication on the ship, he would tear it up and throw it over the side. A couple of months after I arrived at NAVFAC Centerville Beach, he ordered all copies of Time Magazine removed from the base because the cover of one issue displayed a picture of a woman in a bikini. But I kept a low profile and managed to avoid running afoul of his prejudices.

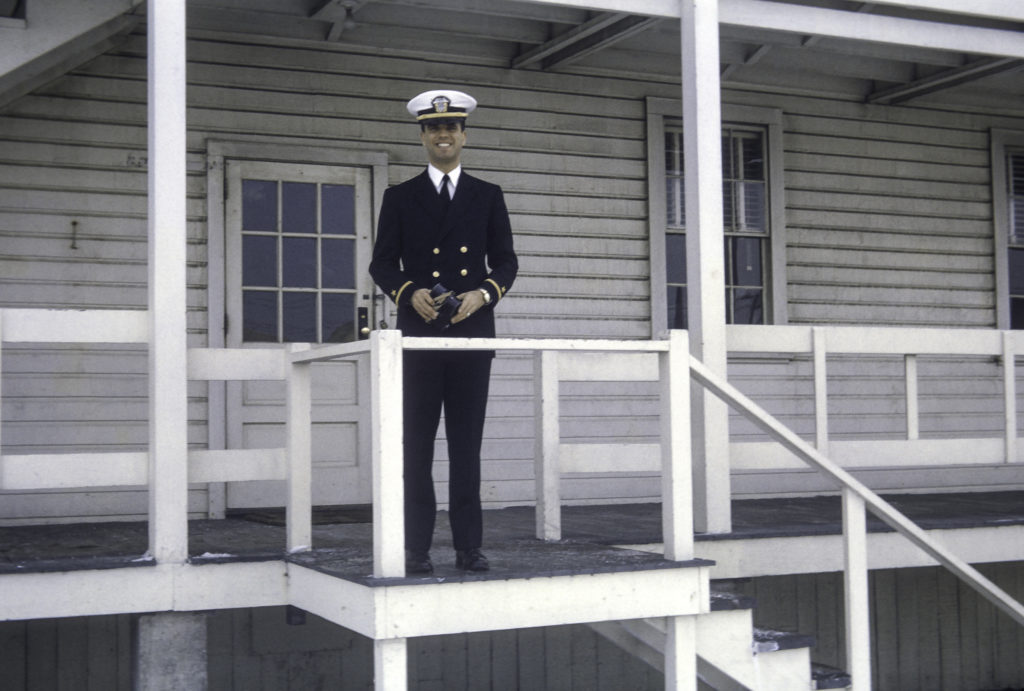

At NAVFAC Centerville Beach, as a single officer, I lived in the Bachelor Officer’s Quarters (BOQ). At the outset there were two other officers living there – Skip Sedlak, the XO, and Lee Elliott, the base Maintenance Officer, like me a new arrival. I had been at Sonar School in Key West with Lee, who was from Los Alamitos, California, right next to my home town of Long Beach. We got along well with one another, but Lee did not get along well with Skip Sedlak. The BOQ had one serious shortcoming which made life there (even disregarding Sedlak’s presence) quite unpleasant. The plumbing and heating system was badly designed, and the piping was put together such that the steam from the heating system created a water hammer effect which resonated throughout the BOQ at night, making sleep impossible. You could stop it temporarily by opening a valve to drain water from the piping, but it would soon start up again. Skip Sedlak ordered Lee as Base Maintenance Officer to fix the plumbing and eliminate the water hammer. This, it turned out, would have required a redesign of the plumbing and heating system, for which there was no budget, and was far beyond the capabilities of the base maintenance shop in any case. This meant nothing to Skip, who didn’t understand plumbing despite his years in the submarine service. When Lee failed to fulfill the order, Skip restricted him to the base indefinitely. This could have proved quite unpleasant for Lee, but fortunately for him it didn’t last long. After a few weeks Skip retired from the Navy, and as he drove out the gate on his way to civilian life, Lee was following right behind him in his Corvair with a big grin on his face.

Sedlak was also responsible, according to a story I heard from some people on the base, for a deterioration in relations with the local community. Prior to his arrival, I was told, the officers on the base had enjoyed frequent invitations to attend the functions of the Ingomar Club, the premier social club of Humboldt County, which was headquartered in the famous Carson mansion in Eureka. But after Sedlak had come around a few times, his boorish and crass behavior alienated the members of the club, and the invitations stopped, leading to a lamentable decline in the quality of life for the officers at Centerville Beach. I don’t know whether this story is true, but it’s at least believable, and it does illustrate what kind of a reputation Skip Sedlak “enjoyed” on the base.

I barely managed to avoid incurring Sedlak’s active enmity myself. Once in the BOQ he spotted a robin on the grass outside. He told me to watch the robin while he went to get his .22 rifle so he could shoot it. I saw no reason why he should want to shoot a robin, so while he was off fetching his .22 I ran outside and scared it away.

I have already mentioned that I drove a Triumph Spitfire; Lee Elliott had a Chevrolet Corvair (see picture above). One time I raced Lee from Ferndale to the base, a distance of about five miles. He beat me. He was probably a better driver, but his Corvair was pretty impressive for a car which was supposed to be “Unsafe at Any Speed.” I always thought that Ralph Nader, whose book by that name was generally thought to have led to the demise of the Corvair, was full of crap. Why didn’t he rag on the VW Beetle, which was surely less safe than the Corvair? I knew several people who rolled VWs in tight curves, but I never knew anyone who rolled a Corvair. I figure Nader’s major accomplishment in life was to discourage all technical innovation in Detroit, with the possible exception of his run for president in 2000, which had the result of drawing enough votes away from Al Gore to get George W. Bush elected.

Anyway, Lee didn’t remain long in the BOQ because a place in Navy housing in Ferndale soon opened up, and he was able to move his family up from Los Alamitos. His place in the BOQ was taken by a new arrival, John Powers. John was an austere, prudish fundamentalist Christian, not the kind of person I, an agnostic bon vivant, was likely to become best pals with. While I was there, his major pastime was taking flying lessons, which was admirable, but I’m somewhat acrophobic and wasn’t interested in becoming a flier. Strangely enough, while stationed at Centerville Beach, I did make a stab at flying, but it was not voluntary on my part. The XO (Skip Sedlak’s successor) was a naval aviator who had served as navigator on a P-3 Orion antisubmarine aircraft. Even while on shore duty naval aviators had to put in their quota of flight time to continue receiving their flight pay. The XO did that by driving down to Moffett Field in the San Francisco Bay area, boarding a P-3, and doing a ridealong, sleeping in a bunk in the back of the aircraft while it performed its mission checking ships off the coast. He took me along on one of these trips. The pilot and plane commander, LCDR Coor, invited me into the cockpit while we were flying at cruising altitude over the ocean. It was a fine day and the view was great. The co-pilot left his seat for a while to take a break. LCDR Coor invited me to sit in the co-pilot’s seat, which I did. Then he told me to take control of the aircraft so he could take a break. I protested that I had never flown an airplane and wasn’t qualified to do do. He retorted that it wasn’t an obstacle – flying a plane was natural, “just like feeling a woman’s leg.” I retorted that I hadn’t had much experience at that either, but he was insistent, so I grabbed the control stick. Immediately the plane went into a nose dive. I pulled up on the stick. The P-3 took off into the stratosphere. When I finally got it leveled off, the pilot told me to bring the plane around to a course of 180 degrees. I pushed the control stick to the right. The plane came around to 180 degrees – then 190, 200, 210, 225, etc. I pulled the stick the other way. The plane came back to 210, 200, 190, 180, then 170, 160, 150, 130, 90 and so on. By this time I was beginning to panic and wondering if the plane carried parachutes and rafts. In the meantime, my XO back in his bunk was getting annoyed at the constant gyrations the plane was performing, which kept him awake. Finally, operational considerations intervened and LCDR Coor took back control of the plane so he could zoom down and take a close look at a suspicious merchant ship. Thus ended my first and only flying lesson.

At NAVFAC Centerville Beach, the single enlisted men, of course, lived in the enlisted men’s barracks, pictured above. The married men, officers and enlisted alike, lived in naval housing in Ferndale. The enlisted men at NAVFAC Centerville Beach were (unlike the officers) a varied and colorful lot. A few months before my arrival, one of them who was on sentry duty had spotted one of his mates, a fellow named Ballard, and pulled out his .45 ACP and shouted jokingly, “Ballard, I’m gonna shoot you!” and he did. He thought the pistol was unloaded, and it wasn’t. Fortunately he didn’t kill Ballard, but that was the end of his sojourn at NAVFAC Centerville Beach.

Another incident, in which I was involved, featured a sly and unscrupulous radioman from Spokane named Galle. The enlisted men were paid in cash, and one payday a man in my division (Oceanographic Research) came to me with a complaint that he had gone to receive his pay and found that it had already been disbursed. It turned out that someone had collected his pay for him because he was on watch at the time and could not fetch it himself; but the someone who collected it hadn’t turned it over to him. That someone, it soon became apparent, was Galle, who eventually confessed to the theft. I never could figure out why Galle, who seemed to be a pretty smart cookie, thought he could get away with such a transparent trick. He was subsequently brought to Captain’s Mast, a kind of naval judicial proceeding where the judge and jury consists of the Commanding Officer, and given a relatively minor punishment.

The NAVFAC’s military mission, which officially was “Oceanographic Research,” was performed in a windowless structure called the T Building. T stood for Terminal. That was because it was where the cable – actually two cables – from two hydrophone arrays out at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean – terminated. The cables transmitted sounds picked up by the hydrophones, and converted to electronic signals, to an array of equipment in the T Building which further processed the signals, converting them into 150-volt electric current which was used to draw lines on sheets of paper called lofargrams. The lines on the lofargrams varied in intensity according to the strength of the signal at any given frequency. Ships emitted sounds at particular frequencies according to type; a ship’s specific sonic emission pattern was called its “acoustic signature.” Merchant ships had their own set of distinctive signatures, military vessels operating on the surface had their own types of signatures, and submarines had still different acoustic signatures depending on their origin, mode of operation, type of propulsion, etc. Diesel subs and nuclear subs had very different types of signatures. Soviet subs were noisy; ours were quieter. I don’t remember that we ever picked up a Soviet sub when I was at Centerville Beach, though there were numerous false alarms. Anyway, life in the T Building was incredibly boring, especially for watch officers. Officers had to stand 8-hour (12 hours on weekends) watches around the clock, and almost nothing ever happened. It was a serious struggle to avoid falling asleep. The enlisted men who stood watch had to watch the lofargrams and write up everything they saw on forms designed for the purpose, and that kept them awake, more or less. The forms were then passed to radiomen in an adjoining room, who typed the numbers on the forms on teletypes, which then sent the data via encrypted landlines to the headquarters of the Oceanographic System Pacific on Treasure Island in San Francisco. Typing kept the radiomen awake. There was little to keep the officers awake. They were supposed to review the forms, but this was more honored in the breach than the observance, except when an unusual signature was detected. You could walk around and inspect the lofargrams, or pester the crew, or walk the T Building looking for enemy agents, but these activities were not enough to fill the vast stretches of dead time; and I couldn’t keep from dozing off now and then, especially during the midwatches (graveyard shift to civilians). On one occasion, a lieutenant named Ed Murphy came in to relieve me early in the morning and found me nodding off in the watch officer’s chair. He called me on the carpet (figuratively speaking, since there were no carpets in the T Building), noting that traditionally, military personnel who fell asleep on watch in time of war were shot. Of course he was right, but I resented it anyway, partly because Ed had himself objected to having to stand watches on a regular basis because of his elevated rank. He was a full Lieutenant, whereas all the other watch officers were Ensigns or Lieutenants Junior Grade (LTJG in naval parlance). Lieutenants were normally assigned to NAVFACs like Centerville Beach only as Executive Officers or Operations Officers. Ed was indeed an exceptional case. He came from Arcata, I think, which was a bit north of Eureka, in the metropolitan area of mostly rural (and remote) Humboldt County. His family owned a store there. His father had died suddenly of a heart attack and, in order to keep the store afloat, his mother needed help, so the Navy assigned Ed to the nearest naval facility, which happened to be Centerville Beach, on humanitarian duty. But Arcata was miles away from NAVFAC Centerville Beach, about an hour’s drive on lousy roads, and it was hard on Ed to help run the store and perform his military duties at the Facility, especially standing watches. He protested, to little or no avail except to arouse the hostility of the other officers, who would have to stand extra watches if he didn’t serve his time (we were already short-handed because the Vietnam War was drawing off people who would otherwise have been assigned to NAVFACs). So when he read me the riot act, I responded by telling him what all the other officers on the base thought of him. To his credit, he defused the situation with a conciliatory remark and let the matter drop. I was transferred to San Nicolas Island not long after, and Ed continued to serve at Centerville Beach a little while longer. I don’t know whether he managed to stabilize the situation with the family store, but eventually his humanitarian duty ended and he was given a “real” assignment: He became the executive officer on the USS Pueblo. On January 23, 1968, just as I was about to leave active duty in the Navy, the North Koreans captured the Pueblo and took the crew hostage, imprisoning and torturing them for a year until they were finally released.

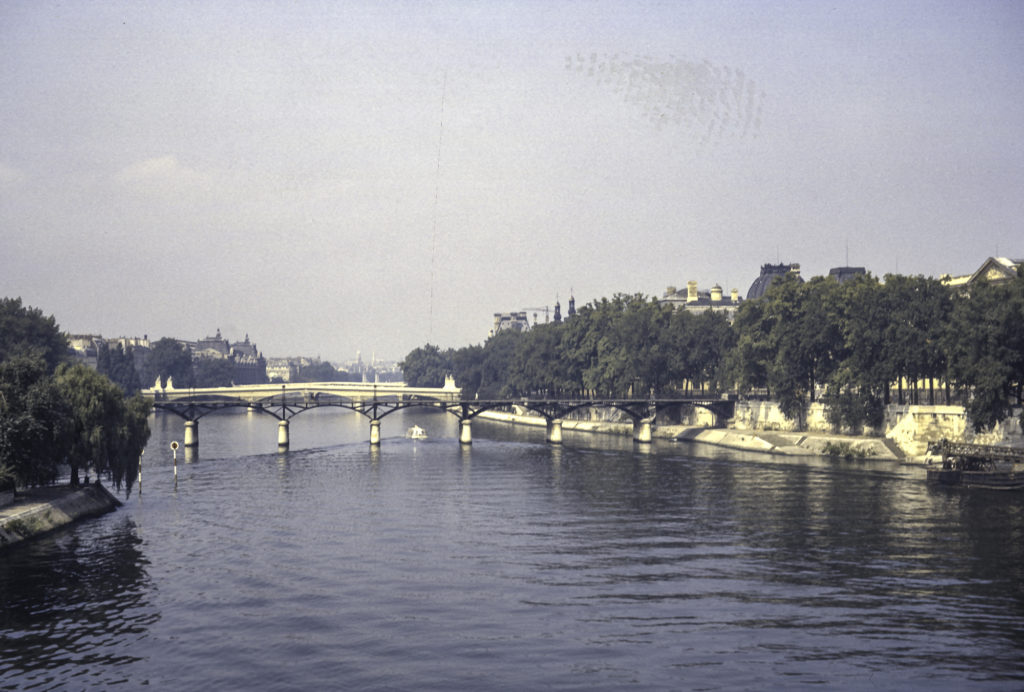

After I had been at Centerville Beach for a few months, the CO and XO retired and a new regime took over. The new CO, Lieutenant-Commander Jack Vosseller, was the son of a vice-admiral and was determined to live up to the family name. Up to then most COs of SOSUS stations had been older men who were on their way out of the Navy and had been given the command position as their last stop before retirement. Vosseller’s appointment was supposed to be a signal of change – the SOSUS stations had acquired a higher profile as their ability to detect Soviet subs improved, and with this enhanced capability supposedly went a heightened emphasis on assigning up-and-coming people to the top NAVFAC jobs. However, I’m not sure whether this was for real or for show. LCDR Vosseller had started out as a naval aviator like his father the admiral, but had crashed too many airplanes, so then he tried the submarine service; but there he got into an altercation with his qualifying examiner, flunking his operational qualification and leaving him with the less prestigious surface navy as his only remaining option. Undiscouraged by these setbacks, he set out to make a name for himself by turning NAVFAC Centerville Beach from a spartan backwater outpost into a veritable paradise on earth. But he labored under several disadvantages. First, too many resources, material and human, were being siphoned off to the war in Vietnam. There were severe budgetary limitations and a shortage of qualified personnel, especially in the ratings associated with construction and facility maintenance. LCDR Vosseller wasn’t interested in any of these “excuses.” He was always going to Lee Elliott (the Base Maintenance Officer) with grandiose plans for construction of new amenities, such as a social club, bowling alley, etc. Lee would tell him that there was no money in the budget and nobody with the expertise to do the work required. The second obstacle was that nobody wanted to do any of the work involved or even reap the benefits of the work once it was completed. The single men (including me) mostly hated the place and wanted only to get out of there. The married men were more positive about their situation, but they mostly wanted to stay at home with their families and work as little as possible. Nevertheless, and amazingly enough, the CO did realize his plans for a club and a bowling alley, if not much else (he never did anything about the BOQ water hammer issue, for example). The club was named the Sea Shanty. I attended on opening night, to which a number of the townspeople were invited. I remember that some of them kind of looked down their noses at the Navy people. A couple of nubile young women were wandering through the crowd, and I heard one of them say loudly, “Doesn’t anyone here speak French?” I did, not too badly at that time, but I didn’t like her snotty demeanor so I didn’t say anything.

The CO started a bowling league, and tried to get me to join, but I brushed him off. I wasn’t interested in doing any recreation on-base; every chance I got I took off for Oregon or San Francisco. In retrospect, I hated the base and the area so much that I couldn’t give Vosseller an even break. Humboldt County is beautiful, and there is lots to do there if you’re an outdoor type, but at that time I wasn’t into any of it. Lee Elliott, more mature and resourceful (he was older and had come up through the ranks), was able to get involved with the locals in doing things like hunting and fishing. Years later, I would have jumped at the chance to go hunting and fishing, but at that time my priorities lay elsewhere. Women, for example. There weren’t many ways to meet women in the area. The most likely method would have been to go to church. I’m not a churchgoer. And Skip Sedlak’s alienation of the locals closed off some of the other possible avenues. But basically the problem was that I wasn’t interested in getting involved with the locals, who seemed to me a somewhat dull and uninteresting lot.

My highest priority at the time was the operational mission of the base, which did hold my interest. But that didn’t turn out well either. I started off on the wrong foot with the enlisted men, who found me an arrogant know-it-all and stuck-up popinjay. They soon put me in my place. One day while I was standing watch one of the men passed me what purported to be an SOS from a local lightship. A lightship was a ship that served the function of a lighthouse, to warn other ships away from potential hazards on the coast. The lightship was supposedly communicating through the hydrophone array to announce that it was in distress and needed help. I had the feeling that something was fishy, but played along with it and wound up swallowing the bait whole. After a few exchanges back and forth, with the messages from the “lightship” growing increasingly agitated, and me growing increasingly puzzled about how to respond, my relief showed up and explained to me that the whole business was a hoax, a practical joke played on me by the enlisted men to demonstrate that I was just a neophyte and not a very smart one at that. I took the hit with good grace and from then on got along much better with the men.

In fact, maybe I was too much on their side. When the new CO and XO took over, they were accompanied also by a new Operations Officer, whose name was Jess Kelly. The Operations Officer was my immediate boss. I got along well enough with his predecessor, Larry Brown, who called Ensigns (which I was) “insects.” Larry had his shortcomings – like anyone else – but he was a paragon compared with Jess Kelly, who, though he was an aviator, and so in theory was supposed to have something resembling a brain, was a few cards short of a full deck. He seemed to know or care little about the operational side of SOSUS; his major focus was on cleanliness. His favorite activity was to point to something and say, in a Texas drawl, “Iyuts feyeelthee.” Not that he was wrong; the place could use some sprucing up. The trouble was that the enlisted men had long since grown accustomed to a regime that didn’t place top priority on spit-and-polish; they saw shore duty as a time to enjoy life and do as little work as possible, and they had been getting away with it for a long time. They figured that any extra time spent in making improvements to the physical appearance of the T-Building should be compensated by less time spent in off-watch training and analysis of lofargrams, and they had ways of enforcing their preferences. I didn’t disagree with Kelly about cleaning up the place and making improvements, but when it came at the expense of operational performance, I was at loggerheads with him.

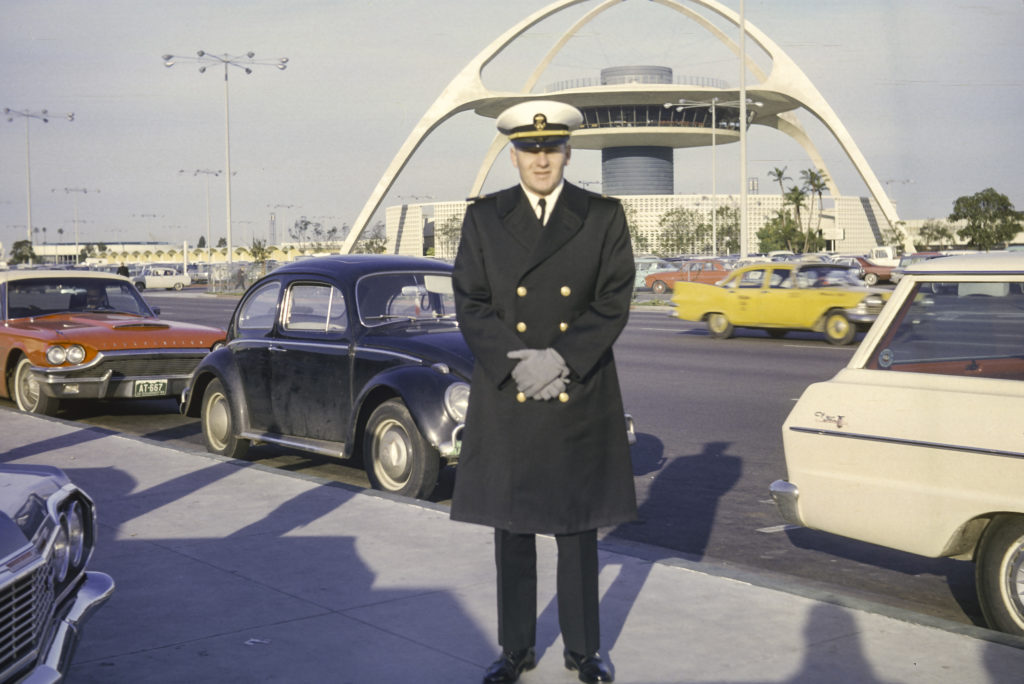

In the end I made myself so obnoxious to the CO, XO and Ops Officer that Vosseller got the Navy to transfer out after I had spent only ten months at Centerville Beach. At least I’m pretty sure that’s what happened. I had put in for sea duty almost as soon as I had arrived there, before the change of command, but had been turned down; the Navy’s response was that it had spent a lot of money training me for duty in the SOSUS system, and it needed to recover its investment. If I wanted sea duty, I had to wait until my three-year mandatory stretch of active service was up, then apply for an extension with sea duty specified. I normally would have spent two years at Centerville Beach, so I’m pretty sure that LCDR Vosseller, with the connections that a scion of a vice-admiral’s family would have possessed, told someone in BuPers (the Navy Bureau of Personnel) that he needed to get rid of a thorn in his side, and would they please find somewhere else where they could stick me without violating any rules. The Bureau obliged by transferring me to NAVFAC San Nicolas Island, which, being on an island 60 miles off the coast of Southern California, qualified as sea duty, but also was part of the SOSUS system. Jack Vosseller may have thought he was having me punished for being an enfant terrible (which I certainly was) but he actually did me a tremendous favor, because being transferred to San Nic was the best thing that happened to me in the Navy. I should have thanked him profusely, but at the time my feelings about Centerville Beach were so negative that it never occurred to me to do so.

NAVFAC Centerville Beach had been commissioned in 1958. I was stationed there from April 1965 to February 1966, a period of ten months. Some time after I was transferred to NAVFAC San Nicolas Island, a tremendous underwater earthquake destroyed one of the Centerville Beach hydrophone arrays, severely impairing its detection capabilities. I think that the defunct array was eventually replaced, but I don’t know when. The North Coast of California, like all the rest of the state, only more so, is subject to severe earthquakes, and NAVFAC Centerville Beach underwent three of them in 1992. This may have provided the motivation to move the Facility’s operations to Naval Ocean Processing Facility (NOPF) Whidbey Island, which did not exist when I was in the service. From what I’ve been able to gather, the transfer was accomplished by “re-termination” of the detection apparatus to the NOPF, and that this entailed replacement of the underwater cables by some other means of transmission, but I have no information about the exact medium involved. In any case, NAVFAC Centerville Beach was decommissioned in 1993 and the site became a ghost town.

There is a detailed article about the SOSUS System on Wikipedia, for those who are interested.