Our four-day sojourn in Paris was intended, I think, as a time to unwind and relax after an intense, sometimes stressful, two weeks in the USSR and a grilling on our experiences there by the emigre scholars of the Institute for the Study of the USSR in Munich after our return. It didn’t entirely turn out that way.

It’s well known that August is not the best time of the year to go to France. Most French people insist on taking vacation the entire month, or as much of it as they can, and those who can’t, e.g. because they have to stick around to cater to tourists foolish enough to venture to France in August, are generally not in a jovial mood, and even less inclined than usual to be nice to stupid Americans who can’t speak or understand French perfectly – people like me.

That said, I still had a good time in Paris and, although I found the Parisians sometimes curt and impatient, I encountered no outright rudeness or hostility. What I did encounter was more bizarre and unexpected, and I’ll be relating that shortly.

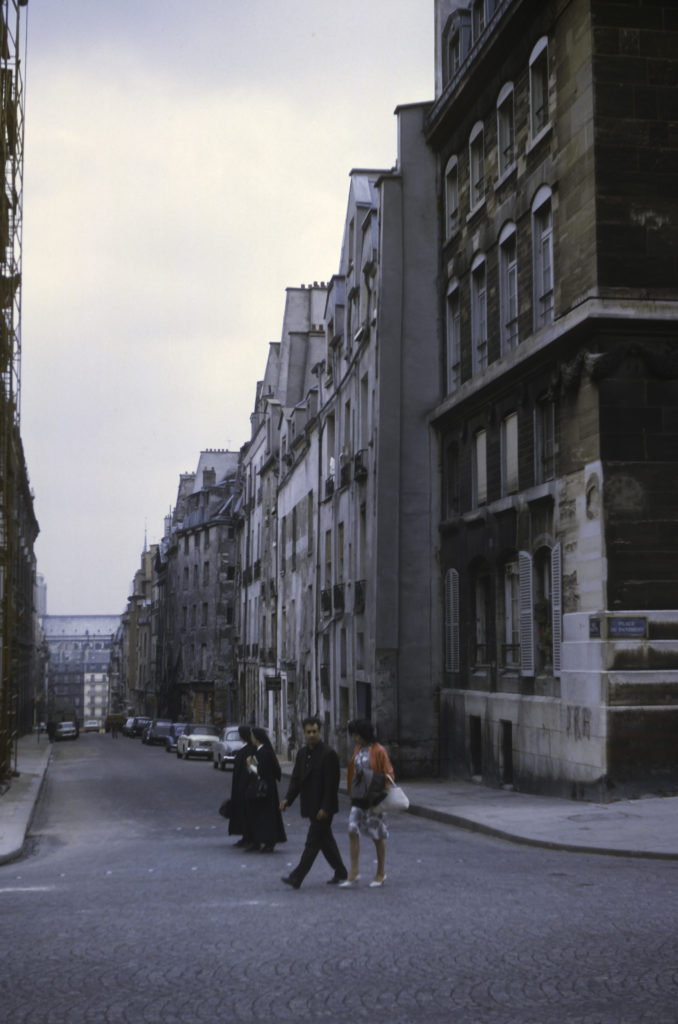

I didn’t try to take in all the major tourist sights while I was in Paris. Instead I spent much of the time wandering around the streets, either alone or in company with my fellow-students from the Munich Institute and the USSR trip.

One place where I did encounter a bit of outright rudeness was not in Paris itself, but in the Air France Boeing 707 on the way there from New York – that was before Munich and the USSR trip. At one point I asked for a glass of champagne, and received a curt “Non” in response (and I was not under-age; I was 23 at the time). I think the stewardess was just too busy at the time. Far more unpleasant was the person in the seat behind me, an American woman, who became enraged when I reclined my seat slightly, and started pounding on the back of it with her fist. I retaliated by reclining my seat all the way back, upon which she shouted “ARE YOU CRAZY?” I replied “Yes, and crazy enough to do you serious harm if you continue in this vein,” or words to that effect. Actually, I didn’t really say that, because before I could, the flight attendants stepped in and calmed her down, explaining that everyone had the right to lean their seat back. And this was in the days when seats in jet airliners weren’t quite the cattle-feed-lot cages that they are now, and you had a lot more space to move around.

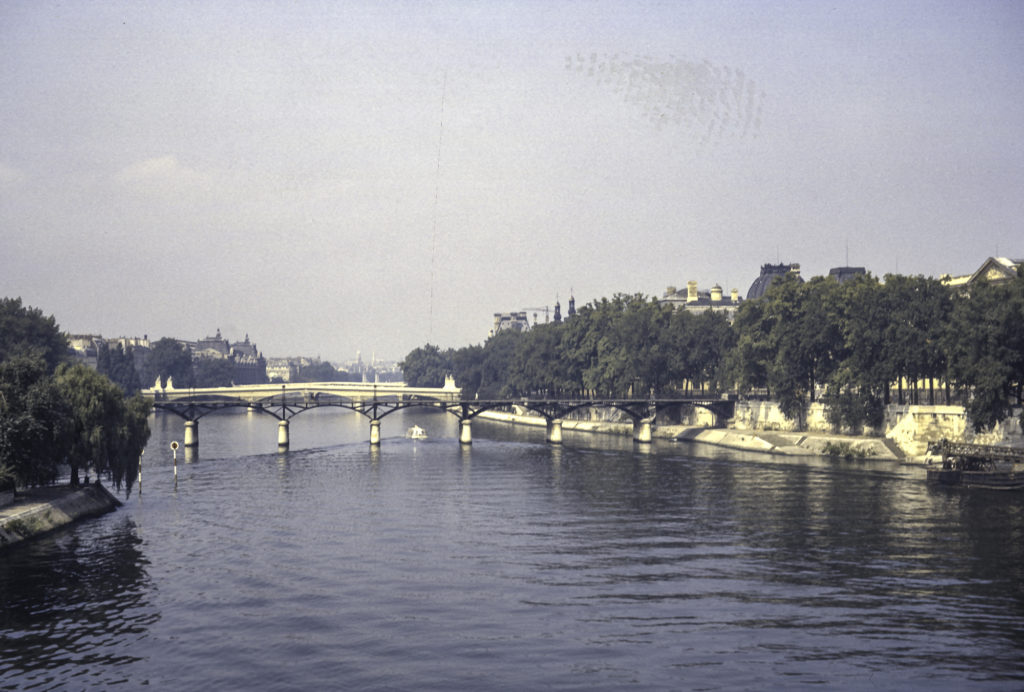

I found Paris itself delightful, enjoyed strolling along the Seine and seeing the parks, monuments and fountains. One fountain that caught my fancy was the Font Saint-Michel, dating from 1860, depicting the Archangel St. Michel and the four cardinal virtues. On either side there is a dragon which spews water into the fountain.

So I didn’t visit the Louvre or ascend the Eiffel Tower on this visit (in fact I still haven’t done either). But on the second day I did take the train out to Versailles, along with Diane, one of the girls from the USSR trip. All of my remaining Paris photos – at least those which have survived – are from Versailles.

Diane and I sat opposite one another on the train, in window seats. I was reading a copy of the English-language Paris edition of the New York Herald-Tribune. This was 1964, and there was a front-page article about race riots in Patterson, New Jersey. A young couple came and sat down in the seats next to us and started talking volubly in French. The woman sat next to me, the man next to Diane. Diane, who had complained a lot about the conditions on the trip in the USSR, said to me, “These French stink almost as bad as the Russians do.” She hadn’t noticed that the girl also had a copy of the Herald-Tribune and said at one point, regarding the article about race riots, “Je pense que c’est une étude bourgeoise.” A few minutes later she turned to me and said, “I’m from Patterson, New Jersey.” It took me a minute to realize that she was speaking English and when I didn’t say anything immediately, she repeated, “I’m from Patterson, New Jersey.”

The girl’s name, as it turned out, was Sharon Gordon. She was indeed an American and I presume that her claim to be from Patterson, New Jersey, was genuine, though it could have been just a conversational ploy to get my attention. What definitely was phony was that she claimed to be working for the “Socialist” Party in Paris. As we got to know each other, during the course of a long day in Versailles, it became increasingly clear that she had more than socialist leanings – she was seriously pro-Soviet. Moreover, her boyfriend, as I took him to be, was also not French: he was Soviet, his name was Andrei, and he claimed to be from Moldavia, the son of a captain in the Soviet Navy.

Diane, who had been put off by the couple from the start, was increasingly less interested in keeping company with them as the day wore on; also it was a warm day, she became overheated and tired, and before long she made her excuses and headed back to Paris. I continued to wander around Versailles with Sharon and Andrei, and got to know them a little better, especially Andrei.

Andrei – I don’t remember his last name, or even whether he ever told us what it was – turned out not to be Sharon’s boyfriend, at least not on a permanent basis – it was clear that they had been sleeping together, but apparently only on a casual basis. In fact he claimed to have another American girlfriend, whom he wanted to marry. He said that he would like to get together with me again while I was in Paris, and before we parted we made arrangements to meet the following day.

Meanwhile I continued my explorations of Versailles. After touring the main palace, I strolled through the gardens roundabout. These were and are formal French parterre gardens, which are highly structured and elaborately designed, featuring flowerbeds and hedges shaped into intricate geometric patterns and symmetrically distributed amidst pools and pathways.

From the French gardens, I continued on to the outlying areas of the Domain de Versailles, in particular Le Grand Trianon, Le Petit Trianon and Le Hameau de la Reine. The Grand Trianon was built initially as a retreat for Louis XIV, in which he could escape the constricting etiquette of the Palace (nevermind that it was he who had established the elaborate and rigid protocols of Versailles in the first place). The Petit Trianon is a much smaller chateau, built during the reign of Louis XV for the King’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour. She died before it was finished in 1668, but upon its completion Louis XV bestowed the Petit Trianon on his next mistress, Madame du Barry. When Louis XVI succeeded to the throne in 1774, he gave it to his Queen, Marie Antoinette, who was responsible for the next addition to the Versailles complex, Le Hameau de la Reine – the Queen’s Hamlet, a rustic retreat near the Petit Trianon.

The first structure I encountered on my way to the Hamlet was the Temple of Love, a classical rotunda built in 1777, well before the Hamlet itself, which was constructed between 1783 and 1785. The Temple is situated in an English garden, which is less ordered and more natural-looking than the formal, highly stylized and “manicured” French gardens that surround the main Chateau of Versailles. Since the Temple was merely a rotunda with columns and provided no privacy, I doubt whether much love actually took place there.

Le Hameau de la Reine was created as a place for Marie Antoinette to meet informally with her friends and to amuse herself by playing at being a peasant, while nevertheless being surrounded by all the comforts of aristocratic life. It includes among other things a working dairy farm, which supplied the Queen with milk and eggs; vineyards, orchards and vegetable gardens; streams, fishing ponds and meadows; a mill; and a barn which doubled as a ballroom.

The buildings of the Hamlet are done in a peculiar style that combined Norman-French with Flemish elements. The largest building in the Hamlet is La Maison de la Reine, which contained the Queen’s private quarters, parlors and salons.

La Maison de la Reine actually consists of two buildings connected by a covered gallery. The first contains, on the ground floor, a dining room and “game room” used for playing backgammon. The upper floor contains a salon where the Queen could meet with her guests; an anteroom known as the “Chinese Cabinet”; and a living room with a harpsichord which the Queen herself played. The second building has a billiard room and a five-room apartment with a library.

Though the Mill had an operating waterwheel which was turned by a stream flowing from one of the ponds, no grain was ground there, because no mechanism for that purpose was installed inside the building. The waterwheel was for decoration only. The building actually housed the Hamlet’s laundry facilities.

The smallest structure at Le Hameau de la Reine was known as Le Boudoir, which provided the Queen a place for solitude or for intimate meetings with a few of her friends. Le Boudoir probably contributed to the image in the popular mind of Le Hameau as a place where the Queen held wild orgies and cavorted with various male and female lovers (which was not true).

Back in Paris, I met up again with Andrei and Sharon, and became more closely acquainted with them (or at least with Andrei) than I would have preferred. I’ve already mentioned that Andrei claimed to have an American fiancée. He further related that while in Paris she had a nervous breakdown and had to return to the States, where she had been committed to a hospital, and could not now return to France. For his part, as the son of a high-ranking Soviet military officer, he could not go to the US except on a tourist visa, under which marriage was not allowed. He asked me whether I had any idea how he could find a way around this obstacle. I was at a complete loss as to how to respond to him, and furthermore his story seemed rather dubious to me. If his girlfriend was a nut case, why would he want to marry her? And why was he involved with Sharon, and what was she all about? It had already become apparent that she was, if not a Communist Party member, at least an outspoken Soviet sympathizer. Every time I made a remark about our trip to the Soviet Union which could be interpreted in any way as disparaging, Sharon would immediately jump to their defense, following with disparaging comments about the USA and Western Europe. By contrast, Andrei at one point assured me that “Mon amie est beaucoup plus Marxiste que moi.” But the question remained of what he was doing in Paris in the first place. He claimed to be studying at a technological institute. In the first place, the Soviet Union had excellent technical colleges of its own; but more to the point, Soviet citizens didn’t get to go abroad to study, or for any other purpose, unless they were exceptionally well-connected. When I commented on this to Sharon, she simply retorted, “Destalinization.” No. Destalinizaton never went that far. Andrei was obviously a member of a privileged elite, and as such he would have been sent abroad for other purposes than just to study.

I introduced the couple to some of the other Americans in our party, including Professor Frey, who immediately discerned that this was no chance encounter and that they were suspicious characters, to say the least. I remained nonchalant about it because I didn’t want to jump to any conclusions, and they didn’t seem to pose any particular threat. Of course it was obvious by now, if it hadn’t always been, that they were Soviet plants – what, really, are the chances of two American tourists just returned from the USSR encountering an American Commie and a Soviet military brat in Paris by coincidence? — And was it just by chance that they happened to sit down in seats next to us on the train? Yeah, right. Still — for what purpose were they set on us? It wouldn’t be likely that they were going to pry any key secrets out of us, because we didn’t have any. Nor would it be to prevent us from indulging in any further nefarious (from the Soviet point of view) activities in Paris, because there was nothing there to do except see the sights. My take on it was and is that the KGB had put them on us just to needle us a little, let us know that they were watching, that they were aware of our association with the Institute and Radio Liberty, and they would keep track of us for future reference. There were of course other possibilities, but they seemed unlikely. Maybe Andrei’s remark to the effect that Sharon was much more Marxist than he as possibly an attempt to disarm me a little, get me to drop my guard by playing the “good cop” as opposed to Sharon’s “bad cop” act. Maybe he hoped I could help him find some way of infiltrating the USA for espionage purposes. Maybe the KGB knew I was about to go into the Navy and wanted him to try to recruit me as a potential spy. At the time I dismissed all of these thoughts as excessively paranoid, and still do. On the other hand, as Henry Kissinger famously said about Muammar Qaddafi, “Even paranoids have enemies.” I’ll never know for sure – the encounter in Paris with Sharon and Andrei had no further consequences that I knew of, I never heard anything from or about either of them again, and the whole episode remains an enigma to this day.