We arrived in Greece toward evening, and immediately everyone in the car sensed a change of atmosphere. Maybe this was partly because we were out of the mountains and it was warmer, but there was more to it than that; the country had a more prosperous and welcoming look to it as well. As we had done the previous few nights in Yugoslavia, we pulled over to the side of the road and spread out our sleeping bags in the fields nearby. In the morning, when we awoke, we encountered some locals who invited us to stop for breakfast in their town, which was called Katerini.

It turned out that the people we met owned a bakery and a cafe. In fact, they owned the whole town. They treated us to breakfast and loaded us with goodies that lasted all the way to Athens. Here is Rob shaking hands with the cafe owner.

After breakfast we continued southward toward Athens, stopping for lunch and rest in a park in the shadow of Mount Olympus, the tallest mountain in Greece and, of course, the home of the gods. I didn’t see any gods (the guy in the striped shirt to the left of the tree is Alan, my roommate in Munich, who was from New York), but it was a great picnic spot.

South of Olympus, the road turned inland, but then encountered the coastline again at the narrow pass of Thermopylae, site of the most famous last stand in history. In 480 BC, King Xerxes of Persia invaded Greece with a gigantic army, aiming to crush the Greeks, who had been a thorn in his side for years, once and for all. The Greeks were forever fighting among themselves and it was only with difficulty that they managed to suspend their internecine quarrels to the extent of raising an army of 7,000 men, plus naval forces, to oppose the Persians. The Greeks, led by King Leonidas of Sparta, decided to meet the Persians at Thermopylae, where the narrowness of the road prevented the Persians from bringing their massive numbers to bear and permitted a small force to deny passage to a much larger one. This worked well for several days, until a Greek traitor led the Persians over a path through the mountains that enabled the Persians to take the Greeks in the rear and outflank them. Leonidas became aware of this in time to send the bulk of the Greek army away before the Persians trapped it; but he remained behind with 300 Spartans to hold the pass long enough for the others to get away. The 300 Spartans, along with 700 soldiers from the city of Thespiai, fought to the death. The Persian juggernaut rolled on south to Athens, which they occupied; but the Athenians had evacuated the city and burned it. The Persian conquest of all Greece seemed imminent, but then the Greek fleet, under Athenian command, attached and shattered the Persian fleet in the Battle of Salamis; and the following year, the Greeks got their act together and defeated the Persian army decisively at the Battle of Plataea, ending the Persian invasion.

Arriving in Athens, we wandered around looking for a place to stay. It was hard to find our way because we couldn’t read the street signs. I knew only the capital letters of the Greek alphabet, but unfortunately the Greeks, like everyone else, use lower case too. However, we soon found that if we stood on a street corner looking stupid, which is never hard for me to do, a crowd of Greeks would soon collect around us and help us figure out how to find what we needed. We needed an inexpensive place to stay, and with the help of people on the street we not only found one, but ended up in the penthouse.

Well, OK, it wasn’t exactly a luxury hotel, and the penthouse didn’t have air conditioning, and the temperature was in the 90s, but on the other hand, we only paid a dollar per night apiece. It was a bargain. Near our hotel was this venerable little Greek Orthodox basilica.

For dinner, we found a nice little taverna nearby and ordered moussaka, a Greek specialty made with eggplant and ground meat. While enjoying our dinner, we made the acquaintance of a 14-year-old Greek girl who was dining at the next table with her family and wanted to practice her English (which was excellent). We were only too glad to take her up on that. She became our native guide, and the next day she and her brother took us to the beach near Piraeus.

This was my first view of the Aegean sea, famed in history and legend. Our hostess went diving for sea urchins, which are considered a delicacy in Greece (as in many other places, but I have never cared much for them), and she got some spines stuck in her foot.

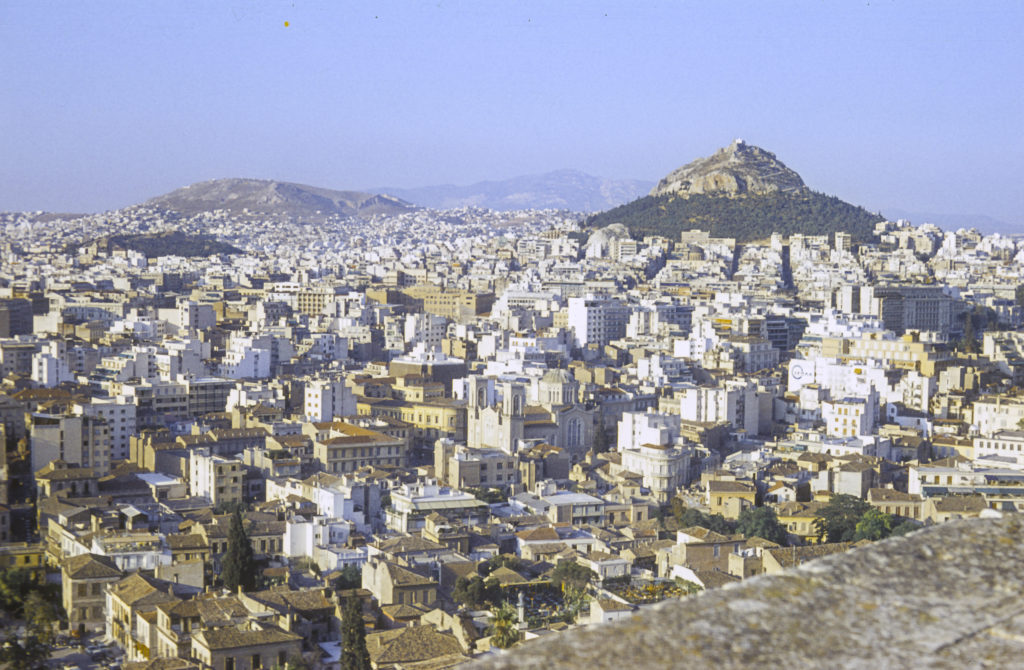

Our Athenian hostess also helped with directions as how best to see the sights of the city. Of course the main stop had to be the Acropolis, the heart of ancient Athens. It was higher than I would have expected, and the view from the top was stunning.

On the south side of the Acropolis are the remains of the Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus, the birthplace of Greek tragedy, dating from the fifth century BC. Here is where the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes were first performed.

The Propylaea is a monumental gateway constituting the principal entrance to the Acropolis. It was intended to provide a fitting approach to the Parthenon, which was in the final stages of construction when the Propylaea was begun in 437 BC. Work on the Propylaea was interrupted by the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC, and never resumed, but the structure was substantially complete by then.

The Erechtheion was a temple to various gods, begun in 421 BC during a truce in the Peloponnesian War and completed in 406. It was named for a mythical king of Athens, Erechtheus. In a war with another city, Erechtheus was supposed to have slain a son of the sea-god Poseidon, but then was himself slain in revenge by Poseidon. Afterward, Poseidon became conflated with his victim, and, under the name Poseidon Erechtheus, was one of the gods to whom the Erechtheion was dedicated. It’s all very confusing.

The figures holding up the roof of the porch on the south side of the Erechtheion are the Caryatids, or Korai in classical Greek. In 1801 the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, claiming to have obtained permission from the Turkish authorities, removed one of the Caryatids and attempted to remove another, but only succeeded in wrecking it. He also took pieces of the Parthenon. He then loaded on shipboard and sent it to England; the ship was wrecked on the way, but after much trouble and expense, the marbles were recovered by divers. Elgin incurred considerable opprobrium for his activities, and eventually sold the marbles to the British Museum, where they remain today.

The crowning glory of the Athenian Acropolis is, of course the Parthenon, perhaps the most famous building in the world. It was built between 447 and 438 BC as part of a building program (which also included the Erechtheion and the Propylaea) instigated by Pericles, the great statesman of Athens’ Golden Age, to celebrate the Greek victory in the Persian Wars and the subsequent rise of Athens to predominance in Greece. The Parthenon was dedicated to Athena, patron goddess of the city, and originally contained a large statue of the goddess, covered in gold. Pictures of the exterior of the Parthenon are ubiquitous; you can find one easily on the Internet, so I’m not going to post one here. Instead I’ll post a couple pictures I took inside the Parthenon.

The Parthenon survived various wars, revolutions, fires, earthquakes and other catastrophes for many centuries. The gold was stripped off the statue of Athena by a later ruler of Athens, Lachares, who used it to pay his troops in 296 BCE. In 276 AD Athens was sacked by pirates, who inflicted heavy damage on the Parthenon and other buildings on the Acropolis, but repairs were made. In the fifth century, when paganism became illegal in the Roman empire, the Parthenon was converted into a Christian church, and the statue of Athena was removed to Constantinople, where it was later destroyed. (Many replicas were made of it in antiquity, so we have a good idea of what it looked like.) After the Turks conquered Greece in the fifteenth century, they turned the Parthenon into a mosque. Nevertheless, the structure remained intact until 1687, when, during a war with Venice, the Turks fortified the Acropolis and used the Parthenon to store gunpowder and also as a shelter for local residents. The Venetians fired a mortar shell into the Parthenon and the gunpowder blew up, killing three hundred people, and causing the worst damage suffered by the Parthenon in its history. (The fact that any of it survived at all is testimony to how strongly it was built in the first place.) In 1801 Lord Elgin, as described above, plundered many of the sculptures and other pieces of the Parthenon which had been knocked off by the 1687 explosion, as well as others that weren’t. When Greece gained its independence from the Turks in 1830, efforts at restoration of the buildings on the Acropolis were begun, but these early attempts were generally ill-conceived and inept, and resulted in more harm than benefit. But since 1975, the Greek government has sponsored a more well-considered program to restore the Acropolis structures, with funding and technical help from the European Union. The Greek government has also held talks with the British about recovering the Elgin Marbles, though these have not yet borne fruit. When I visited the Parthenon in 1964, of course, the restoration program was far in the future, but it was still a grand sight.

Janet, the girl in the picture above, was from Providence, Rhode Island. I kept in touch with her after the trip and when I was in Naval Officer Candidate School in Newport during the fall of 1964, she invited me for Thanksgiving dinner at her parents’ house in Providence. She picked me up in her Morgan roadster – a fairly uncommon car then, and quite rare nowadays – and brought me back afterward. It was a pleasant interlude in an otherwise rather dreary and arduous period, and I was very grateful to her for it.