From the stop at Finse, the train embarked upon the final stretch of the Oslo-Bergen railway. First it passed through a long tunnel, then it embarked on a dizzying descent toward the city of Bergen, allowing me to get some nice photos along the way.

Bergen is one of the most beautiful cities I have ever seen. I caught my first glimpse of it from the train on the crazy-steep descent from the mountains into the city. It has a magnificent harbor in one of Norway’s famed fjords, framed by the mountains. Fortunately I was able to get some shots from the train as it plummeted toward the harbor.

In Bergen I stayed with Sidsel Larsen, one of the Norwegians I had met in the Moscow University dormitory, and she showed me around the city and its environs, starting with the harbor. In Bergen the harbor is ubiquitous; you cannot overlook it. For its entire history Bergen has been a maritime commercial city, as it is today. It was founded in 1070 and grew to be the largest city in Norway, which it remained for centuries until it was overtaken by Oslo in the nineteenth century, and for a while in the 13th century it was also the capital of Norway. It also became an outpost (kontor) of the Hanseatic League, the commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns that dominated trade in medieval northwestern Europe.. (The great medieval city-republic of Novgorod in Russia also hosted a kontor of the Hanseatic League, and I presume that is where the Russian word kontora, meaning office, came from.)

In the medieval period Bergen became a great entrepot for the export of cod caught in north Norwegian waters to the rest of Europe, and was granted a royal monopoly on the trade. The Hanseatic merchants came to Bergen each summer to buy fish from the fishermen from the north; they had their own separate quarter of the town, next to the wharf where their ships docked, which is called Bryggen; it is visible in the picture below.

Sidsel Larsen took me on a walking tour of the Hanseatic Quarter. I was struck by the excellent state of preservation of the warehouses and other buildings. It turns out that they are not the originals; Bergen, like many other Scandinavian and Russian towns, was built almost entirely from wood in premodern times and was subject to terrible fires, the worst of which, in 1702, burned down 90% of the city. The structures I saw have all been built since then, and many of them rebuilt and restored multiple times. Nevertheless they are mostly authentic.

Bergen is one of the rainiest cities in Europe; the mountains surrounding it cause the moist incoming air from the Gulf Stream to rise, cool and precipitate their moisture onto the city. We had to take umbrellas everywhere and frequently found ourselves sheltering from the showers.

One exception to the predominance of wood construction in the medieval city was the Bergenhus Festning, a stone fortress (Fortress) guarding the entrance to the harbor, dating from the 1240s. It contains a tower called the Rosenkrantztårnet, which we were able to climb and get a great view of the city from. I also looked for a Guildensterntårnet, but couldn’t find one anywhere.

On the other side of the harbor, I saw the Norwegian Navy’s latest hi-tech dreadnought, the Statsraad Lehmkuhl, a three-masted barque which is actually used as a training ship for Norwegian naval cadets. It has an interesting history. It was originally built in 1914 as a training ship for the German merchant marine, under the name Grossherzog Friedrich August. At the end of the First World War the victorious British took it over as war booty, but then sold it in 1921 to a former Norwegian cabinet minister named Kristofer Lehmkuhl, who renamed it after himself (Statsraad = “cabinet minister”), and who donated it to his eponymous foundation. In World War II the Germans repossessed it when they invaded Norway, but of course they had to return it to the Norwegians upon being defeated. The Statsraad Lehmkuhl Foundation now contracts it out, mostly to the Norwegian Navy, but also upon occasion to other customers, including, ironically, the German Navy. Although I did not get a chance to board it during my visit to Bergen, years later the ship put in at Long Beach Harbor during a round-the-world summer cruise, and I was able to tour it then.

Bergen is a city built on hills. The seventeenth-century writer Baron Ludvig Holberg, who was born in Bergen, decided that since Rome was built on seven hills, Bergen must be the same. Unfortunately, there is much disagreement as to which ones are to be included in the seven or whether that is really the correct number – many would argue for nine. I think it’s a silly controversy, and the operative maxim is that Bergen is a city of very uneven terrain, with lots of hills and grades. If you like San Francisco, you should feel right at home in Bergen. And I did.

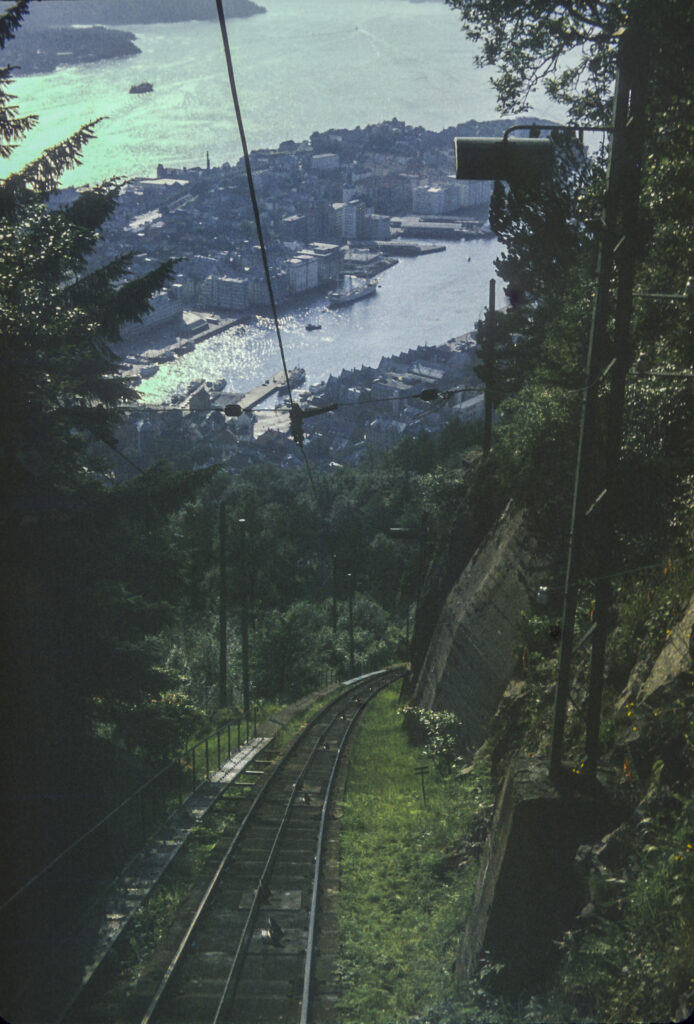

There is a caveat about that, though, which is that I visited Bergen in the summer; in the winter it gets a lot of snow – something you don’t see much of on the California coast. Be that as it may, the two most prominent mountains around Bergen are Ulriken and Fløyfjellet or Fløyen – the second is of course named after me. Fløyen is on the north side of the city, Ulriken to the east; Ulriken is the higher at 643 metres (2,110 ft), Fløyen comes in at 400 m (1,300 ft) above sea level. Both have aerial tramways running to the top. I’m not sure which one appears in the picture below.

Perhaps the most illustrious native of Bergen is the composer Edvard Grieg (1843-1907), who composed the music for my favorite play, Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. (Ibsen, a contemporary of Grieg, came from the town of Skien in Telemark, in eastern Norway.) So it was a big thrill when Sidsel took me on an excursion to Grieg’s house and estate, Troldhaugen (which translates, appropriately for a fan of Peer Gynt, as “Troll’s Hill”). Now, as in 1973 when I visited, it is the Edvard Grieg Museum. When I visited the house itself served as the museum; in 1993 a separate structure was built to house the museum. The house has been described as “a typical 19th-century residence with panoramic tower and a large veranda,” which doesn’t do it justice. Built in 1885, it’s a beautiful late 19th-century house exhibiting not only outstanding craftsmanship but deft artistic features, most notably the wonderful stained glass transom window above the front door.

The Troldhaugen estate is situated on a small peninsula of a large lake or inlet from the ocean, with a jetty projecting into the water.

We scrambled out on the jetty and took pictures of the lovely setting, which were again infiltrated by the ragged rapscallion who had followed me all the way through the Soviet Union.

Grieg and his wife Nina were Unitarians. Upon his death in 2006, Grieg was cremated, and his ashes were interred in a crypt in the side of a hill near his house. His wife Nina moved to Copenhagen after his death, but when she died, she also was cremated and her ashes placed beside her husband’s. Strolling around the estate, we encountered the hillside crypt where their remains are interred.

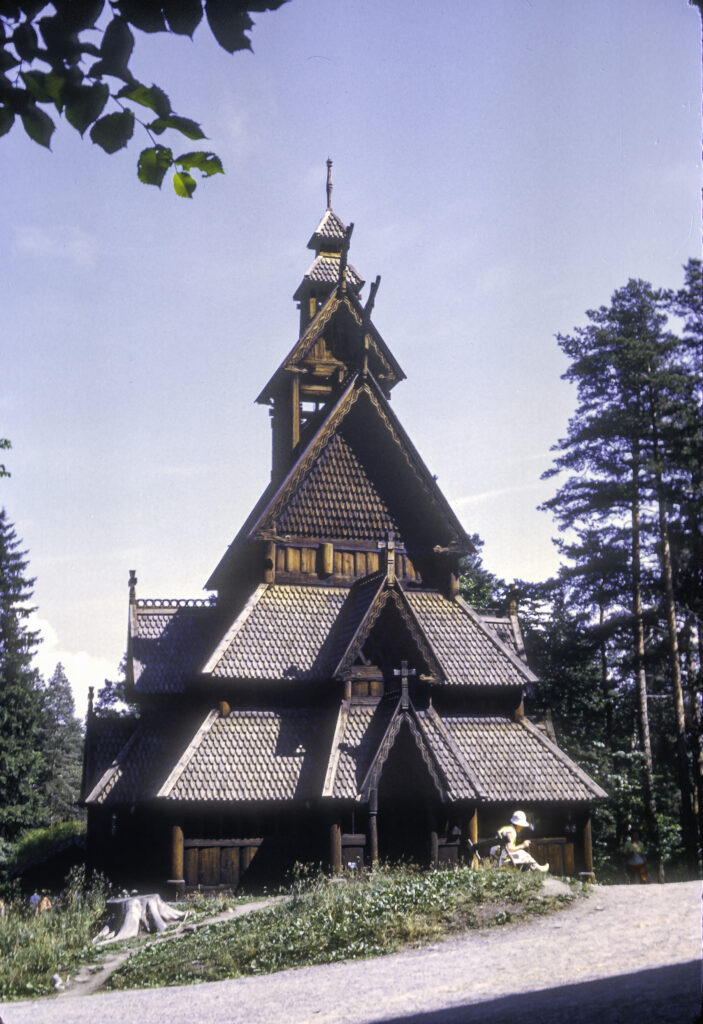

Returning to Bergen, we visited the Fantoft Stave Church. It had originally been built around 1150 at the village of Fortun, near the eastern end of Sognefjord, Norway’s longest and deepest fjord, about 60 miles northeast of Bergen. In 1879 a replacement church was built, and the original was slated for demolition, but was saved by a Norwegian businessman who had it disassembled and moved to Bergen, where it was reassembled.

In 1992, l9 years after I visited the Fantoft Stave Church, it burned to the ground. The cause was determined to be arson. A series of other Norwegian stave churches were also torched, and the police arrested and charged a man named Varg Vikernes with starting the fires. Vikernes was (and is) an interesting, though unsavory, character. He was born in 1973, the same year I visited Bergen. In the early ’90s he became an influential member of the Norwegian black metal scenc. Black metal (most readers will probably know this, but I did not, having never paid much attention to such matters) is an extreme type of heavy metal music, characterized by “fast tempos, a shrieking vocal style, heavily distorted guitars played with tremolo picking, raw (lo-fi) recording, unconventional song structures and an emphasis on atmospheres.” Many black metal artists paint themselves up as corpses and adopt pseudonyms. They also tend to espouse fringe viewpoints and ideologies, including extreme anti-Christian views, Satanism, ethnic paganism, and neo-Nazism. Some of them are fascinated with the lore and imagery of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. Varg Vikernes was such a person. In 1991 he founded a one-man band named Burzum, which is the word for Mordor in the language of that land, which was the abode of Sauron the Great, the evil arch-villain of Middle-Earth and his minions, the orcs. Vikernes had previously been a member of a band called Uruk-hai, a name for a particularly nasty type of orc. He also took the stage name Grishnakh, from one of the orcs in The Two Towers. He flirted with neo-Nazism in his teenage years, and later developed his own ideology, which he described as “Odalism,” a fusion of paganism, traditional nationalism, racialism, environmentalism, simple living, self-sufficiency, and opposition to anything he deemed a threat to his vision of a pre-industrial pagan society, e.g. Christianity, Islam, Judaism, capitalism and materialism.

On August 10, 1993, Vikernes murdered his fellow-musician Øystein “Euronymous” Aarseth, one of the founders of the black metal “scene,” in circumstances that have never been completely clarified (Vikernes claimed self-defense). On August 19, Norwegian police arrested him for the murder of Euronymous, the arson burnings of Fantoft and several other churches, and the theft and possession of 150 kilograms of explosives which were found in his home. (He may have been planning to blow up a leftist enclave with the explosives, but this has never been proven.) In 1994 he was convicted of most of the charges, including the burning of some of the churches, but was somehow found not guilty of torching the Fantoft church. He was sentenced to 21 years in prison, the maximum penalty under Norwegian law (this was also the sentence passed on the mass murderer Anders Breivik), but he was released on parole after 15 years. He eventually moved to France, where he got in trouble with the French police for inciting hatred against Jews and Muslims.

However, in the end the mad vandalism of Vikernes failed in its intended purpose, at least in the case of the Fantoft Stave Church. Work on reconstruction of the church began soon after the fire and was completed in 1997. The restored church now has a security fence around it to impede recurrences of the 1992 attack. The picture below, of course, shows the church as it appeared in 1973.