Tbilisi was a fitting climax to our whirlwind April 1973 tour of Central Asia and the Caucasus. It is a magnificent city and the capital of one of the most distinctive, mysterious and intriguing countries in the world. Georgia, or Sakartvelo as the natives call it, is an ancient, unique and fascinating land. The inhabitants are possibly descended from the original modern humans to people the area and speak a language (actually several languages, the so-called Kartvelian group) related to no other known linguistic family in existence, written in its own script which is derived from neither Latin, Cyrillic nor Arabic. The country is mountainous, rugged, and stunningly beautiful. The men arc noted for being brave and skilled warriors, generous and welcoming but quick to anger, with a strong sense of honor; the women for being beautiful, proud and assertive – a Georgian woman is queen in her own household. Georgian hospitality is legendary, and we were to experience it in full.

Georgians have been Christian since the 4th century CE. Their national church belongs to the Eastern Orthodox branch of Christianity but is autocephalous, owing obedience neither to Rome, Constantinople or Moscow. The Georgian ecclesiastical architecture is also sui generis. Some of the most important examples of this genre are found in the town of Mtskheta, about 20 kilometers northwest of Tbilisi, which was also the destination of our first excursion in the Tbilisi area.

Mtskheta is a very old city; it was the capital of the early Georgian Kingdom of Iberia from the 3rd to the 5th centuries CE, and is still the site of the headquarters of the Georgian Orthodox Church. It lies at the confluence of the Mtkvari and Aragvi Rivers; from there the Mtkvari continues to flow eastward through the heart of Tbilisi.

The crowning glory of Mtskheta is the 11th-century Svetitskhoveli Cathedral. The cathedral’s origins date back to the conversion of the Georgians to Christianity in 337 CE, when a wooden church was built on the site, followed by a stone basilica in the 5th century, and eventually by the current cathedral in the 11th century. The name Svetitskhoveli means “life-giving pillar” and is associated with a Georgian legend which holds that a Georgian Jew named Elias visited Jerusalem at the time of the Crucifixion of Christ, purchased the mantle of Jesus from a Roman soldier, and brought it back to Mtskheta. There he showed it to his sister Sidonia, who took it in her hands and immediately died from overexcitement. The mantle could not be extracted from her grasp and was buried with her; over her grave grew a great cedar tree. Many years later, it was decided to build a church on the site, the wood for which was to be acquired by cutting down the tree. However, the tree refused to fall and instead levitated into the air; when, following a full night of prayer, a local saint persuaded it to return to earth, it formed the first pillar of the new church. Its wood turned out to have magical properties, supposedly emitting a liquid that cured people of disease. The cathedral now contains a ciborium (freestanding canopy supported by columns), dating from the 17th century, under which the mantle of Jesus is supposed to have been buried along with Sidonia.

The current version of the cathedral was built between 1010 and 1029. It is constructed in the so-called cross-dome or cross-in-square style, which features a square central structure called a naos, topped by a dome, with rectangular extensions on the sides to form the overall shape of a cross. The cathedral has been damaged and restored several times since it was first built. It was destroyed by Tamerlane in the late 14th century and then reconstructed, with the present dome added, in the 15th.

Svetitskhoveli Cathedral stands in the middle of a large courtyard, surrounded by walls built in the 18th century. Entrance to the courtyard is from the western wall.

Entrance to the cathedral is also on the west. Originally there were portal galleries on the north and south sides as well. But in the 1830s, in anticipation of a scheduled visit by Emperor Nicholas I, the Russian authorities decided that the cathedral needed to be tidied up a bit and made to look more respectable; they chose to do so first by razing the portal galleries on the sides. They also thought it would be a good idea to improve the appearance of the interior walls by whitewashing them, thereby obliterating a number of priceless medieval frescoes. In the end the tsar’s visit was canceled. Fortunately, modern-day restorers have been able to recover some of the frescoes that were thus obscured.

The eastern facade of the church features two high and deep niches on either side, with a window in the middle illuminating the apse, framed in red stone and surrounded by stylized decorations, including two bull’s heads beneath the window.

Above the window on the eastern facade is a decoration resembling a peacock’s tail; still higher, just beneath the roof, are three small windows, and to the left of those is a bas-relief decoration representing an eagle with spread wings hovering above a lion.

From Svetitskhoveli Cathedral we moved on to the spectacular Jvari Monastery, which stands on top of the mountain of the same name overlooking Mtskheta. The religious significance of this site dates from the early 4th century CE. Legend says that Saint Nino, a female evangelist credited with converting the King of Iberia to Christianity in 337 (and also the same saint who prayed to bring the cedar tree back to earth as described above), erected a miracle-working wooden cross there. The cross attracted pilgrims from all over the Caucasus, and eventually, in 545, a small church was built over it. Later, between 590 and 605, a larger church was built to accommodate a growing influx of pilgrims, and that became the “Great Church” of Jvari, pictured here.

The Great Church of Jvari monastery is perched on the edge of a cliff overlooking the confluence of the Mtkvari and Aragvi Rivers, with a dizzying drop down to the river below.

From its juncture with the Aragvi, the Mtkvari River continues to flow down through the middle of Tbilisi a few kilometers to the east.

The Great Church was built in a style known as “tetraconch” – from the Greek words for “four shells” – which is characterized by a cruciform plan with an apse at the end of each cross arm, and three-quarter cylindrical niches between the apses. (An apse is “a large semicircular or polygonal recess in a church, arched or with a domed roof, typically at the eastern end, and usually containing the altar.”)

The three-faceted apsis (projective enclosure) on the eastern facade is decorated with bas-reliefs depicting scenes of Georgian rulers consorting with Christ and the archangels.

Above the southern entrance to the Great Church is another bas-relief featuring two angels lifting a Bolnisi cross, known as the Ascension (or Glorification) of the Cross. The Bolnisi cross is a Georgian national symbol which traces its origin to the oldest surviving Georgian Orthodox church, Bolnisi Sioni Cathedral, built in the fifth century CE in the village of Bolnisi (which we did not visit). Unfortunately, it closely resembles variations of the cross used by medieval crusading orders, including the Teutonic Knights, which evolved into the Iron Cross used by the German military, with which the Bolnisi cross is often confused.

The monastery complex is surrounded by the ruins of walls and towers, as seen in the picture below. In 1973, at the time we visited, access to Jvari Monastery was supposedly severely restricted because of its proximity to a nearby Soviet military base, but it was a scheduled stop on our tour and we had no trouble getting permission to visit it.

Our lodging in Tbilisi was a typical Soviet hotel, not exactly the Ritz-Carlton but better than some I’ve stayed in. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, it was abandoned for a while, but eventually it became a hostel for refugees fleeing the upheavals in the Caucasus.

There appeared to be some major construction going on not far from our hotel. I never found out exactly what was being built; the concrete structures under the crane in the picture below look like sections of tunnels for subway cars, but if so they must have been replacements for parts of existing lines since the Tbilisi subway had been completed in 1966.

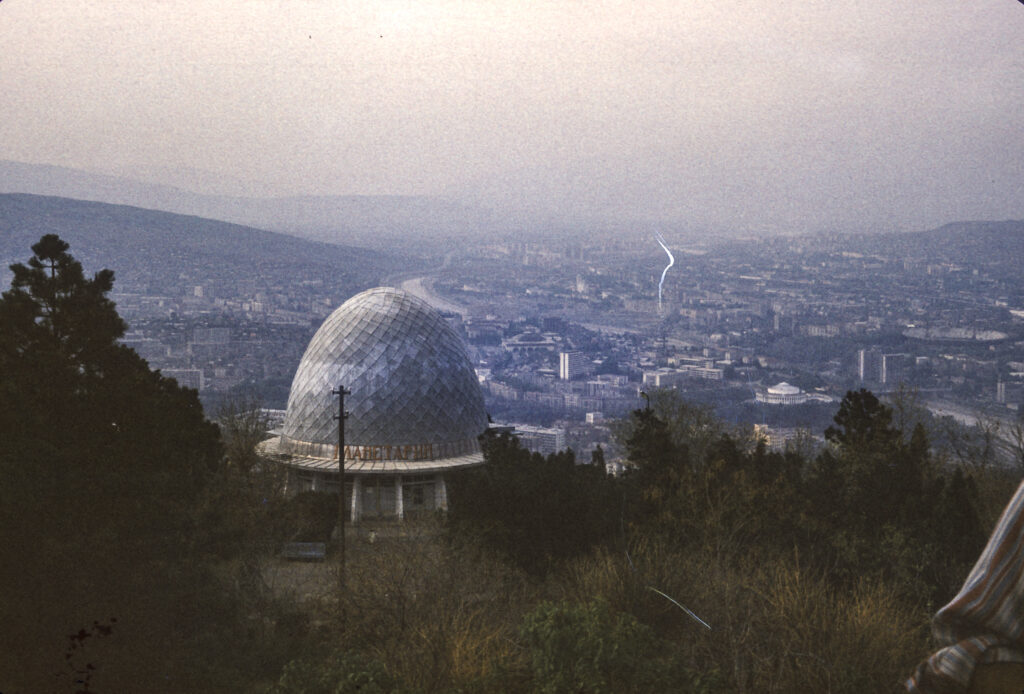

Georgia is a mountainous country, and Tbilisi is nestled amidst mountains. The highest point in the city is Mount Mtatsminda, at 770 meters (2526 feet). In 1930, the Soviet government established a park atop the mountain. TV towers and a restaurant pavilion were also built there.

You might think that Tbilisi, being a very hilly city, would have a number of aerial tramways and cable cars. You would be right, and this was true while we were there. The top of Mount Mtatsminda can be reached both by road and by a funicular railway which has been in existence since 1905. There were also seven aerial tramways. One of them ran from Rustaveli Avenue to the top of Mount Mtatsminda. However, on June 1, 1990, there was an accident on that line which resulted in 20 deaths. The ultimate cause of the accident was never determined, but its lethality was the result of a failure to maintain the equipment properly, causing a malfunction of the brakes which would have stopped the cars if they had been working properly. The line was closed, and after the collapse of the Soviet Union, all the other aerial tramways, and the funicular railway as well, were shut down. In 2012 the funicular reopened, and eventually some of the aerial tramways as well. In 2017, construction began on a new aerial tramway line to the top of Mount Mtatsminda.

We rode the funicular railway up to the park. Halfway up there is a station where one can get off and walk to the Mtasminda Pantheon, a necropolis where a number of celebrities are buried, and which I’ll describe in more detail later.

When we visited, the Mt. Mtatsminda park was just a quiet landscaped area where one could stroll amidst the trees, and the serenity was only occasionally interrupted by events such as the ceremony pictured here. But in recent years, since Georgia became independent again, the locale has been transformed into an amusement park, with carousels, water slides, a roller-coaster, dark ride, funicular, and a ferris wheel.

Up the hill from the restaurant pavilion we came across a flat, open area with a pedestal for a statue, but instead of a statue we found only a Georgian flag. It turned out that the pedestal had once been occupied by a statue of Joseph Stalin.

As one might expect, Mtatsminda Park offers spectacular views over the city. Here is one to the north.

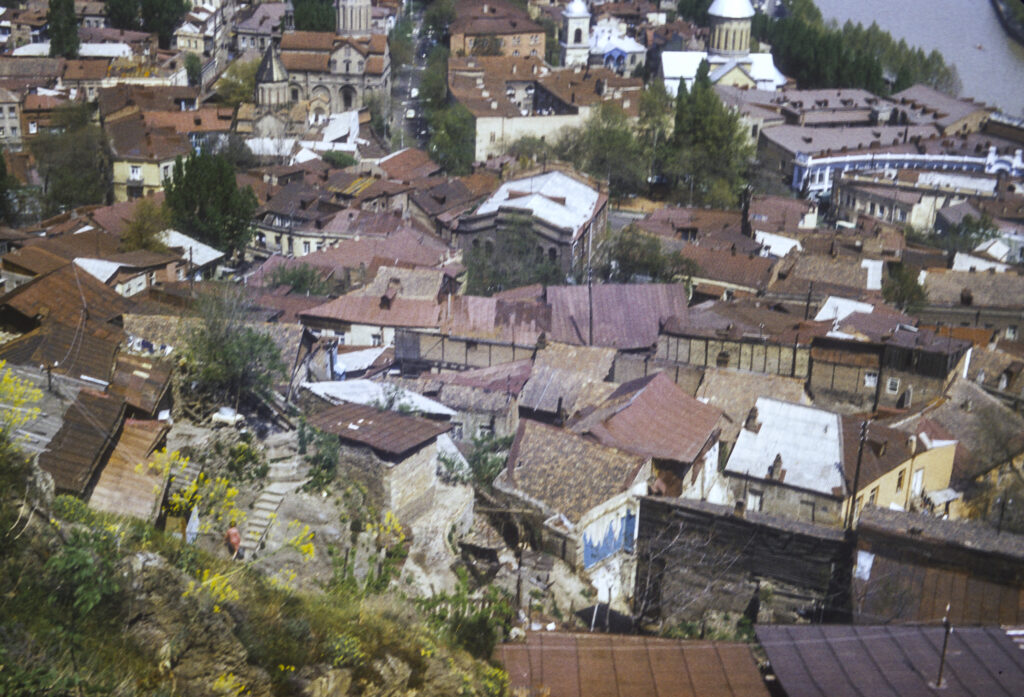

And here is a view to the south. I found, however, that some of my most interesting shots were to be taken from locations lower down, which provided better resolution and enabled me to more easily identify the points of interest.

Taking a bus from the top of Mt. Mtatsminda, we rode down to the Pantheon halfway up the mountain. Debarking from the bus, I was able to admire and photograph some of the fine stonework which borders the winding road leading to the Pantheon.

The Mtatsminda necropolis is located in the churchyard around St. David’s Church, as seen in the following photo taken from Mtatsminda Park. Among the notables buried there are the Russian diplomat and playwright Alexander Griboedov. Chiefly remembered today for his play Gore ot Uma (Woe from Wit), in 1829 Griboedov was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to Persia. Russia had just defeated Iran in the Russo-Persian War of 1826-28 and forced its Shah to sign a humiliating treaty; anti-Russian sentiment in Iran was strong. Shortly after arriving in Tehran, an incident arose in which several Armenian escapees from the royal harem – a eunuch and two women – sought sanctuary in the Russian Embassy. When the Shah demanded their return, Griboedov refused, on the grounds that the Treaty of Turkmenchai, which ended the recent war, Georgians and Armenians held against their will in Persia were to be repatriated to their homelands. The Iranian mullahs refused to acknowledge that this provision applied to women in Muslim harems, and stirred up a mob to storm the Russian embassy, slaughtering Griboedov and the rest of the legation. Griboedov’s body was mutilated and dragged through the streets. Eventually his remains were recovered and returned to Georgia, where he was buried. Also buried at the Mtatsminda Pantheon are Nino Chavchavadze, Griboedov’s wife, and other members of the Chavchavadze family; the first democratically elected president of Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia; and various Georgian artists, scientists, scholars, and public figures.

At the Pantheon I encountered the first, and to my recollection still the only, public drinking fountain I saw in the Soviet Union. Jerman Rose obligingly posed for me to take a picture of him drinking from it.

In one corner of the cemetery I came across a plain marble headstone, with an alabaster decoration, inscribed only in Georgian script. Here was interred one Ekaterina Geladze, the mother of Iosif Vissarionovich Jugashvili, better known as Joseph Stalin.

From Mount Mtatsminda, we took a road which runs eastward on a ridge to Sololaki Hill. To celebrate the 1500th anniversary of Tbilisi in 1958, the twenty-meter-tall (65 feet) Kartlis Deda statue was erected on the top of Sololaki Hill. Also known as Mother of Kartli or Mother Georgia, the statue depicts a woman holding a winecup and a sword—the winecup symbolizing the hospitality accorded to friendly visitors, the sword expressing the readiness to defend against enemies.

The Kartlis Deda site also provides a viewpoint offering some of Tbilisi’s most striking vistas. At the base of Sololaki hill are a pair of fine old churches, the Upper and Lower Bethlehem.

Further to the north of the Kartlis Deda viewpoint, near the river, lie the Sioni Cathedral, the Norashen St. Virgin Mary’s Armenian Church and a church with the improbable name of Jvari’s Mama’s Church.

To the northeast of Kartlis Deda one obtains a stunning view of the Mtkvari River, crossed by the Metekhi Bridge. Near the bridge, on the far bank, is the Metekhi Street Virgin Church, and on the near bank is the St. George Armenian Church. On the bridge stands a statue of King Vakhtang I Gorgasali of Iberia (c. 449-c. 522), traditionally recognized as the founder of Tbilisi.

The Metekhi Street Virgin Church, properly the Metekhi Church of the Assumption, stands on an elevated cliff above the Mtkvari River. I was later able to photograph it from the northeast. It was originally built in the late thirteenth century, during the reign of King Demetrius II, and was damaged and restored several times thereafter. It was built in a style called cross-dome, with three projecting apses on the east side and four freestanding pillars supporting the dome. Stalin’s fellow Georgian and head of the NKVD Lavrenti Beria wanted to demolish it, but somehow it survived; it was used as a theater until the 1980s, when the Soviet regime acceded to popular demand and returned it to the control of the Georgian Patriarchate.

Continuing along the ridge from the Kartlis Deda statue, we arrived at the Narikala Fortress. Originally built in the 4th century by the Sassanian Persians, the fortress was expanded and rebuilt over the years, most recently in the 16th and 17th centuries; but an earthquake in 1827 damaged it badly, and it fell into ruin.

The Narikala Fortress is another great location for capturing panoramic views of the city.

We had plenty of free time in Tbilisi to stroll the streets and wander on our own. Except for the churches, which somehow have survived the vicissitudes of the ages, most of the construction in Tbilisi dates from no earlier than the nineteenth century. Prior to that time, for several centuries Georgia had been carved up between the Ottoman Empire and Persia, with the western part subject to the Turkish sultans, and the eastern areas vassals of the Persian shah. In 1783, however, Erekle II, ruler of the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, hoping to improve the security of his domain by finding a more reliable protector, signed the Treaty of Georgievsk with Empress Catherine II of Russia, which made his kingdom a protectorate of the Russian Empire. Unfortunately this move backfired, provoking a Persian invasion, the destruction of Tbilisi and the massacre of its inhabitants, which the Russians failed to prevent, in 1795. In 1800 Catherine’s successor, Tsar Paul, proclaimed the outright annexation of Kartli-Kakheti to the Russian Empire, deposing the king. Under Tsar Alexander I the Russians secured their control of Georgia by defeating the Persians and forcing them to acknowledge Russian hegemony in Georgia by the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813. Alexander I also began the incorporation of Western Georgia into the Russian Empire, a process which was completed during the Russo-Turkish wars of the 19th century.

The Mtkvari River is very scenic and provided many vantage points for beautiful photos, but it seemed that wherever we went there was this slovenly, disreputable character, perhaps a terrorist, who kept popping up and insinuating himself into my pictures. Somehow we could never get rid of him.

The advent of Russian rule, though heavy-handed and insensitive, provided the peace and security which enabled the rebuilding of Tbilisi to proceed unhindered, and the Russian authorities placed their stamp on the city by devising a new city plan and commissioning new buildings in Western styles.

I remember being impressed by the apparent modernity and prosperity of Tbilisi, and the general European appearance, in contrast to many of the towns we had visited in Russia itself. Also, there seemed to be many foreign cars – Mercedes, Volvo, even a few American cars – on the streets.

Except for the scheduled tours, for which buses were furnished, we did our sightseeing via public transportation. On one occasion, several of us took a bus to the downtown area, and when we got off, I discovered that my wallet was missing. I immediately realized that someone on the bus had picked my pocket. This was was not a hazard exclusive to Tbilisi; in Moscow my first roommate, Ariel, had once had his pocket picked on a subway escalator by a man who had bumped into him pretending to be a drunk. I reported the theft to the guides, though of course I knew that nobody would be able to do anything about it. They were quite apologetic about the incident, but we all had a good laugh when I told them that the stolen wallet, which I had kept in my pants pocket, contained nothing more than seven rubles and an expired California driver’s license. I kept my passport and most of my cash in another wallet, much more securely concealed.

The major legacy of Georgian architecture surviving from before the 19th century are the many Georgian and Armenian churches (historically many of the inhabitants of Tbilisi have been Armenian). The Sioni (Zion) Cathedral in downtown Tbilisi is an outstanding example. Its basic elements date from the 12th century, but it was destroyed and rebuilt many times since then. At the time of our visit, the Sioni Cathedral was the seat of the Catholicos-Patriarch of all Georgia, and remained so until 2004, when it was replaced by the newly built Holy Trinity (Sameba) Cathedral in the Avlobari district on the other side of the Mtkvari River.

On April 12, 1802, the Russian Commander-in-Chief in the Caucsasus, General Karl von Knorring, assembled the nobles in the Sioni Cathedral and read to them the proclamation of the annexation of Kartli-Kakheti to the Russian Empire. He also required them to take an oath of allegiance to the Empire, enforcing it by having the soldiers which he had previously disposed around the cathedral arrest those who refused.

On the last day of our stay in Georgia, our hosts took us to the cave monastery site of Vardzia. The caves were carved in the cliffs of Mount Erusheti, on the south bank of the Mtkvari River over 200 kilometers west of Tbilisi. Although cave settlements have existed there for thousands of years, it was only in the twelfth century CE that large-scale development of the site began. Most of the work was done in the 12th and 13th centuries, during the “Golden Age” of Georgia under Queen Tamar. A severe earthquake in 1283 devastated Vardzia, and though it was partially rebuilt, further development was at an end. With the decline and fragmentation of Georgia in the 14th and 15th centuries, along with ruinous foreign invasions, Vardzia fell into decline. In the 16th century, after the division of Georgia by the Ottoman Turks and the Safavid Persians, with the eastern areas going to the Persians and the western parts, including Vardzia, to the Ottomans, Vardzia was abandoned.

Our tour bus brought us to a pleasant park setting, presided over by a stone church nestled under the cliffs towering nearby.

Whatever notes I took at the time have not survived, and I don’t remember the name of the church or anything else about it, such as when it was built. I think it must have been of relatively recent construction. The main church at Vardzia is the Church of the Dormition, which is carved out of the rock at the foot of the mountain, but it was not open to the public at that time.

From the church, we proceeded up a path to the foot of the cliffs, where we were able to get a closer view of the caves in which the monks had lived.

Some members of the group even tried to climb up to the caves themselves, but I don’t think any of them actually made it that far.

After we tired ourselves out hiking round the site and taking pictures, our Georgian guides lit a fire and prepared a barbecue for us, which served as our farewell dinner. They had brought abundant supplies of pork, beef and lamb, which they cut up into kebabs and roasted over the fire. In the Caucasus, shishkebab is known as shashlik, and this usage has spread to Russia as well, where kebab restaurants are known as shashlichnye. Our hosts had also brought abundant supplies of Georgian wine, and we feasted and toasted our hosts until nightfall.

The next day we boarded a TU-104 twin-engined jet for Moscow. This was our second flight on a TU-104; we had also flown on one from Tashkent to Tbilisi. I don’t remember much about the first flight, but I do remember the second. The Tbilisi airport is distinguished by a takeoff runway with a sharp drop-off, in fact a high cliff, at the end, so if the aircraft hasn’t reached takeoff speed by the time it reaches the end of the runway, the results can be unpleasant. The TU-104 was the world’s second passenger jet aircraft to enter service, after the British Comet in the early 1950s – not an auspicious precedent since the Comet was taken out of service following several disastrous crashes which resulted from design defects. The TU-104 also had its problems. It was unreliable, unstable, control response was poor, and it had a tendency to stall at low speeds. This last shortcoming caused pilots to make their landing approaches at higher than recommended speeds, with attendant risks. One person I knew had been on a TU-104 flight to Kiev, where the aircraft came in too fast, overshot its touchdown point and ended up a couple hundred feet beyond the end of the runway in a swamp. Our flight from Tbilisi was relatively sedate, but I do remember that when taking off the aircraft seemed to take forever to get up to takeoff speed, and I wondered whether we were going to fall off the end of the runway before we became airborne. The plane did dip a little when the runway ended, but did not stall, and off we went to Moscow. On the plane I sat next to my Moscow roommate, Chris Buck. On our approach to Moscow, the crew turned off the cabin pressurization at 15,000 feet. The drop in pressure causes Chris’s sinuses, which had been giving him trouble, to explode, and I was alarmed to see him suddenly doubled over in agony. Fortunately this didn’t last long; the pressure shortly equalized and by the time we landed he was more or less back to normal.

Later I learned a little verse that Russians sang about the TU-104: TU-sto-chetyre luchshe v mire samelyot, Skazal, vylezaya, obuglennyi pilot. “The TU-014 is the best airplane in the world, said the charred pilot as he crawled out [of the burned cockpit].” The TU-104 was retired from service in 1979.