Our final stop in Central Asia was Tashkent, the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. After the glories of Bukhara and Samarkand, Tashkent was a letdown. Like the other two cities we had visited, it was a major stop on the Silk Route, but little was left of its pre-Soviet heritage. A powerful earthquake in 1966 had leveled most of the old city, and it had been rebuilt as a “model Soviet city,” i.e. lackluster and boring. Thus there was little of historical interest to see. Nevertheless, we found plenty to do there.

I can’t remember the name of our hotel, and there was nothing much else memorable about it either, but at least it was a real hotel, with basic amenities like bathrooms.

Tashkent was quite open and spacious, with wide expanses between structures. Our hotel was located in an outlying residential district, situated amidst clusters of brand-new apartment buildings with children playing in the wide vacant spaces between the structures. In contrast to Bukhara and a lesser extent Samarkand, where we could walk from our hotel to many of the sights we wanted to see, in Tashkent we had to take the bus to get anywhere. (Sputnik did furnish tour buses in all the cities we visited, but only in Tashkent did we need it on a full-time basis.) Our tour schedule in Tashkent was leisurely, and since there was no place easy to get to by walking and public transportation was something of a mystery, we spent a lot of time in our rooms, from which we had excellent unobstructed views.

Chris Buck, who was my roommate in Tashkent as well as in Moscow, passed the time by reading the local newspapers. In one of them there was an article about a gang of criminals who had been apprehended after staging armed robberies of payroll offices in a number of large factories, including some where the gang’s members were employed. (In the USSR workers were generally paid in cash, so payroll offices tended to have large sums of cash on hand.) In the course of their crime spree the bandits had shot and killed people, so that when they were put on trial, some of them received death sentences. According to the newspaper article, just before pronouncing sentence on one of them, the judge asked him, “Why did you rob the very place where you worked? Didn’t you realize that your comrades couldn’t get paid?” “Yes, Comrade Judge,” replied the bandit, “but then I couldn’t get paid either.”

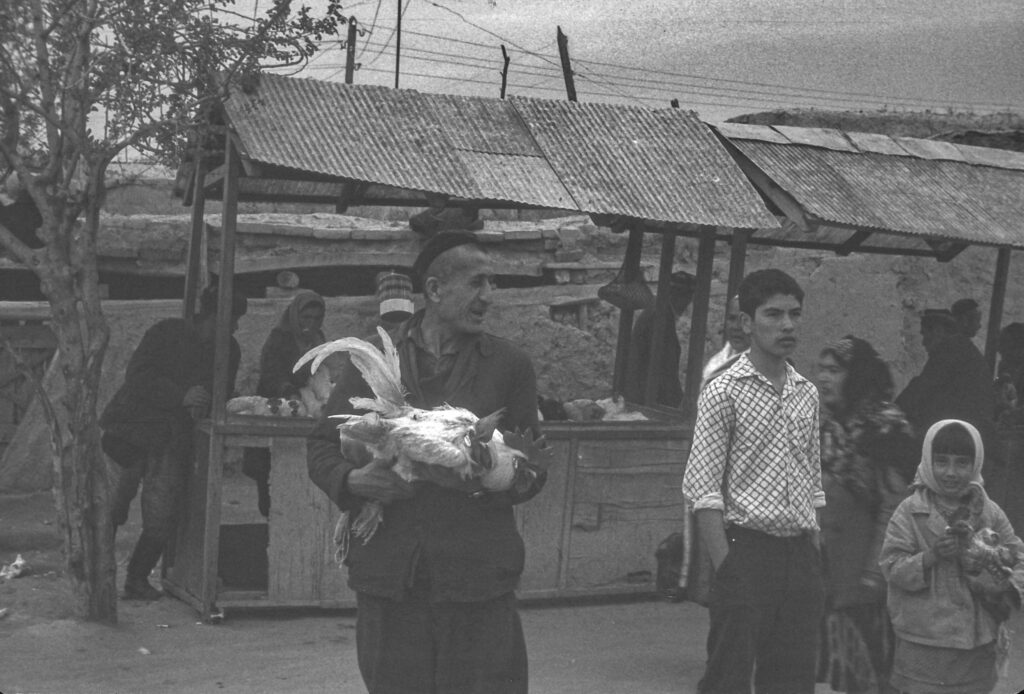

Perhaps because it was the capital of the Uzbek SSR – capital cities in the USSR always seemed to be better-provisioned – food in Tashkent seemed to be more plentiful and of a higher quality than elsewhere in Central Asia, and we took full advantage of this abundance. Above all we hogged out on plov – rice pilaf – which is the Uzbek national specialty. The basic recipe calls for chunks of meat, onions and grated carrots, often with other fruits and vegetables such as chickpeas, raisins, apricots, etc. in the mix, There are many different variations of plov, and the food stands and street vendors which were ubiquitous in the city (not to mention the restaurants) sold them all. We hardly ever ate in the city’s restaurants.

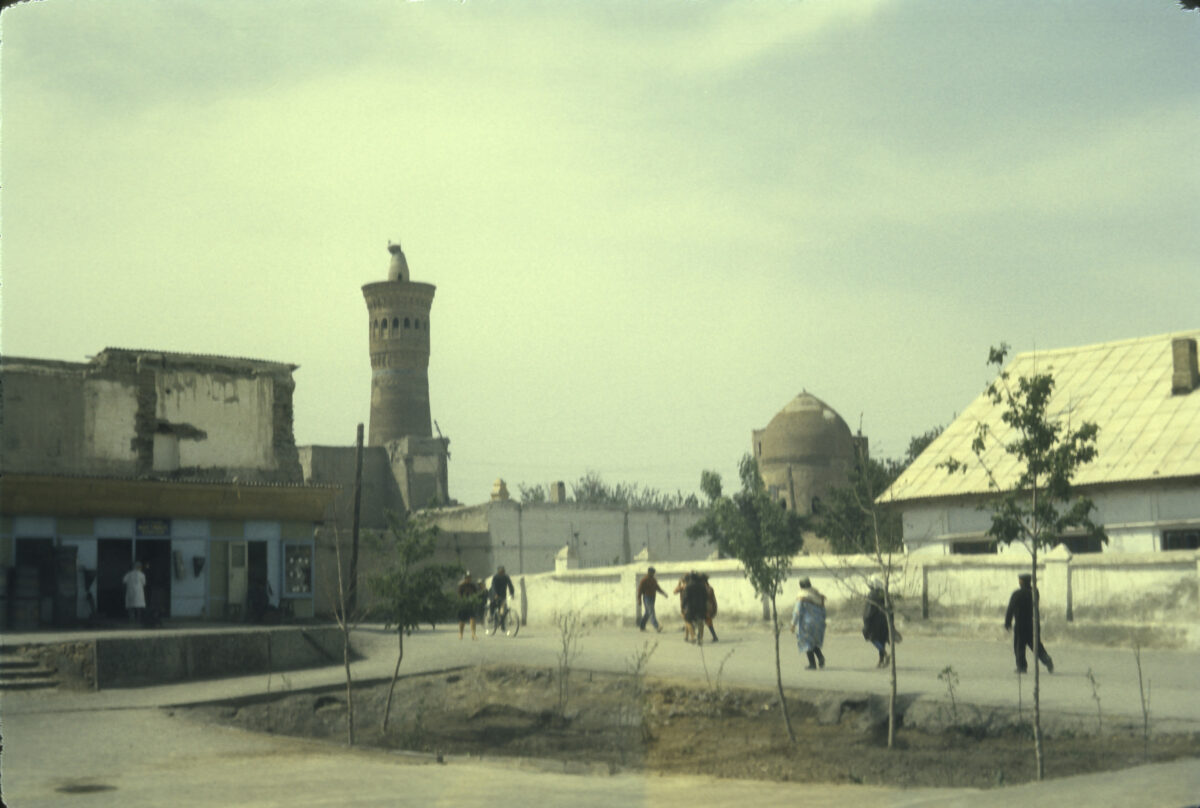

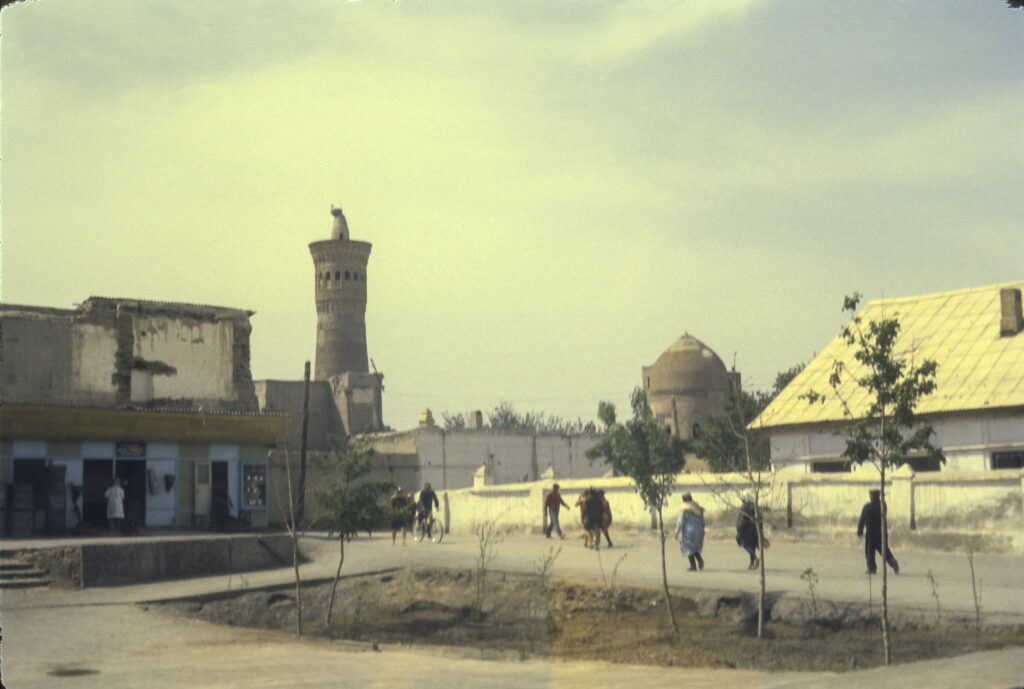

The earthquake that struck Tashkent in 1966 measured only 5.1 on the Richter scale, but its epicenter was in the center of the city, and buildings in the densely packed older quarters were especially vulnerable to the tremors. Relatively few people perished in the quake, although official Soviet figures of 15 killed are considered untrustworthy, and other estimates place the number at anywhere from 200 to 5,500. Over 80% of the city was destroyed, including somewhere between 75,000 and 95,000 homes and most of the old mosques and other historic buildings.

The Soviet government responded to the disaster with a massive rebuilding effort, dispatching considerable resources and large numbers of workers from other Soviet republics to participate. Many of the workers who came to the city in that period stayed, resulting in a net increase in the population of the city and a change in its ethnic makeup. By 1970 100,000 new homes had been built, more than enough to replace those lost in the earthquake, but still not enough to accommodate the new arrivals, and more were needed.

When we visited, seven years after the earthquake, it seemed that the reconstruction efforts had not slackened. New buildings were going up all over Tashkent, and construction was proceeding at an especially frenzied pace as one ventured into the city center. All kinds of structures – office buildings, shopping centers, hotels, etc. were going up, many of them quite massive, but few, it seemed, of any special distinction or interest. A major exception was the Lenin Museum, seen in the picture below.

That the most original and striking new architectural work in the capital of Uzbekistan should be dedicated to Lenin, who never set foot in the place, would seem to be not only outlandish but rather an affront to the Uzbek people, who have their own proud history; so it is not surprising that when Uzbekistan became independent, the name was changed to the State Historical Museum of Uzbekistan. As I recall, although the exterior of the Museum was certainly worth a picture, none of our party went inside to view its contents, which would have been unlikely to include anything that we had not seen in Moscow or Leningrad.

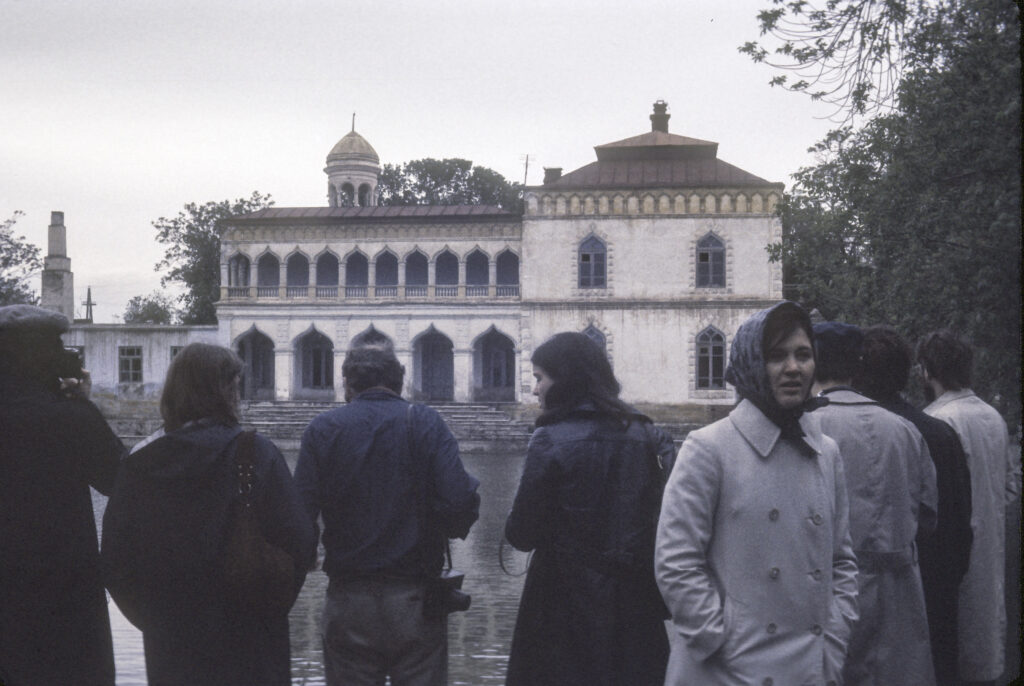

There was some irony, especially after we had seen Bukhara and Samarkand, in the fact that so many of the attractions we saw in Tashkent, including those which had survived the earthquake, were structures built by Russians. One such was the palace or mansion of Grand Duke Nikolai Konstantinovich. Grandson of Tsar Nicholas I, nephew of Tsar Alexander II, he was the proverbial dissolute scion of the royal family. A prodigious womanizer, he became involved in an affair with an American actress, Fanny Lear; having spent all his money on her, and unable to borrow more, he stole some diamonds from the revetment (frame) of a treasured family icon. The theft was discovered, and to hush up the scandal, Nikolai was declared insane and banished to Tashkent, where he spent the rest of his life.

Once in Tashkent, he seems to have turned over a new leaf, and committed himself to good works, such as building canals, schools and a theater. He also built a magnificent mansion to house and showcase his large and magnificent art collection. He died in Tashkent in 1918, and the Soviet regime nationalized his mansion and its contents. The mansion for a while became a museum, but in 1935 his collection was moved elsewhere, and is now in the national Museum of Art of Uzbekistan. The mansion is now used as a reception hall for the Uzbekistan Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

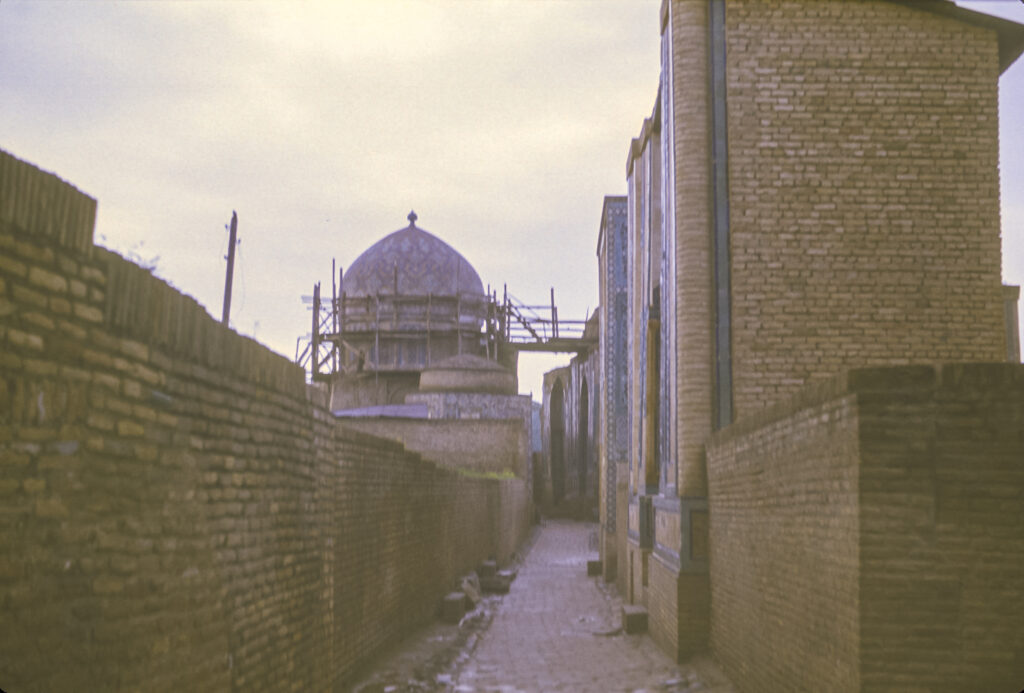

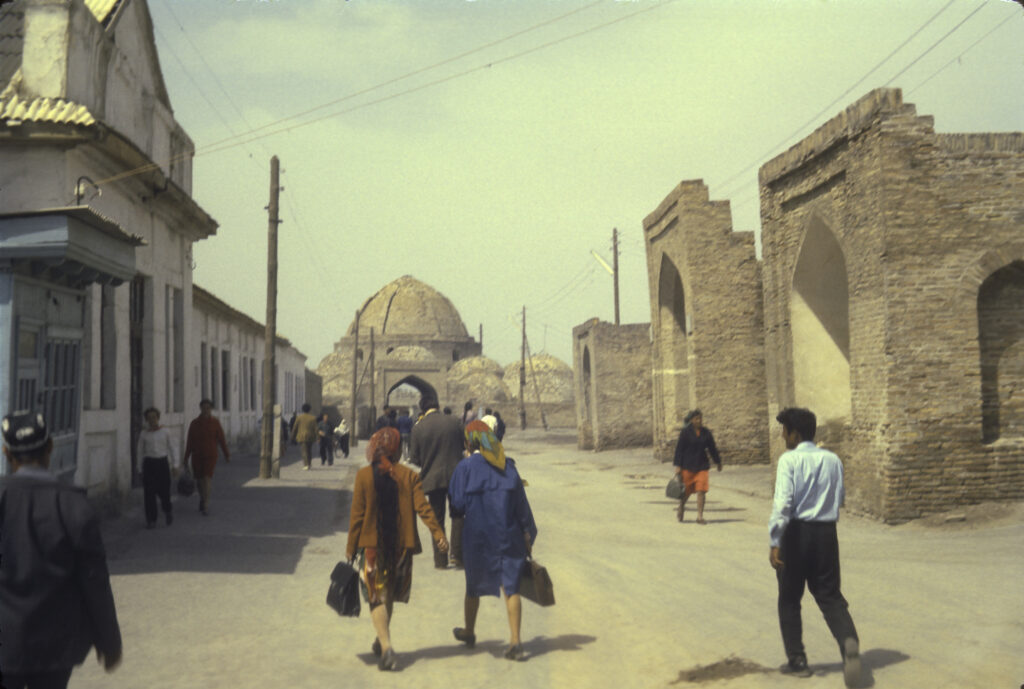

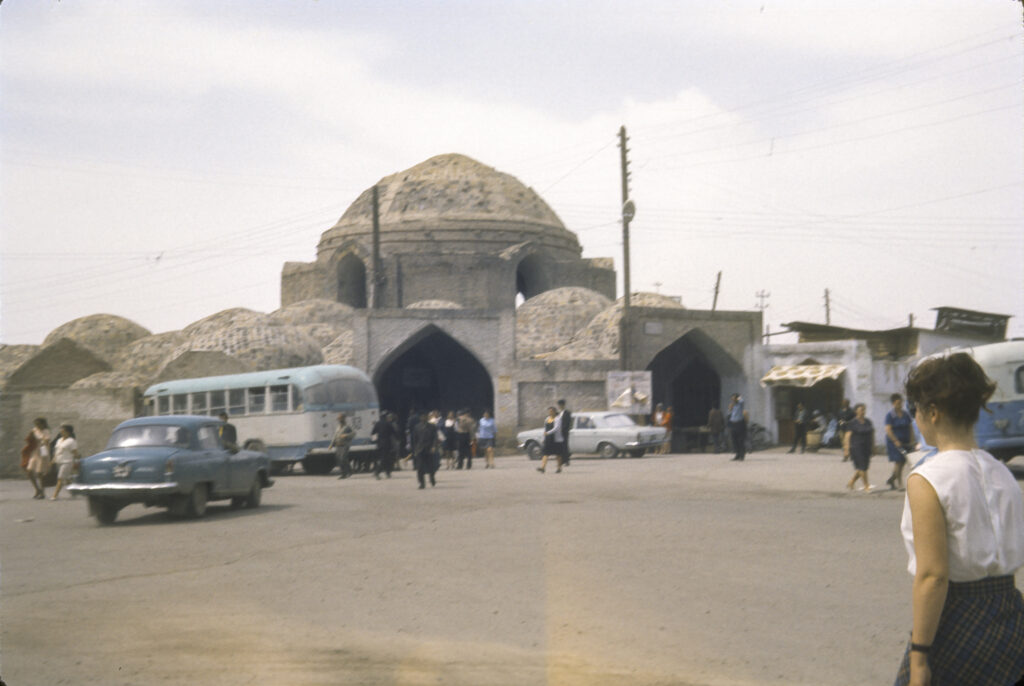

Not all of the Islamic monuments dating from before the Russian conquest were destroyed in the earthquake, but as far as I can recall our tour did not include any of them. On one occasion, I vividly recall, we were on the tour bus with an Uzbek native guide who started to talk about some of the more interesting historical sites, when another, more senior guide, apparently an ethnic Russian, got on the bus and quite literally shoved the Uzbek guide aside, started talking about Tashkent’s newest and most palatial hotel (not the one where we were staying), how many rooms it had, how much it cost to build, how spiffy and wonderful it was, etc. I wonder if this turkey ever realized how close he came to being lynched.

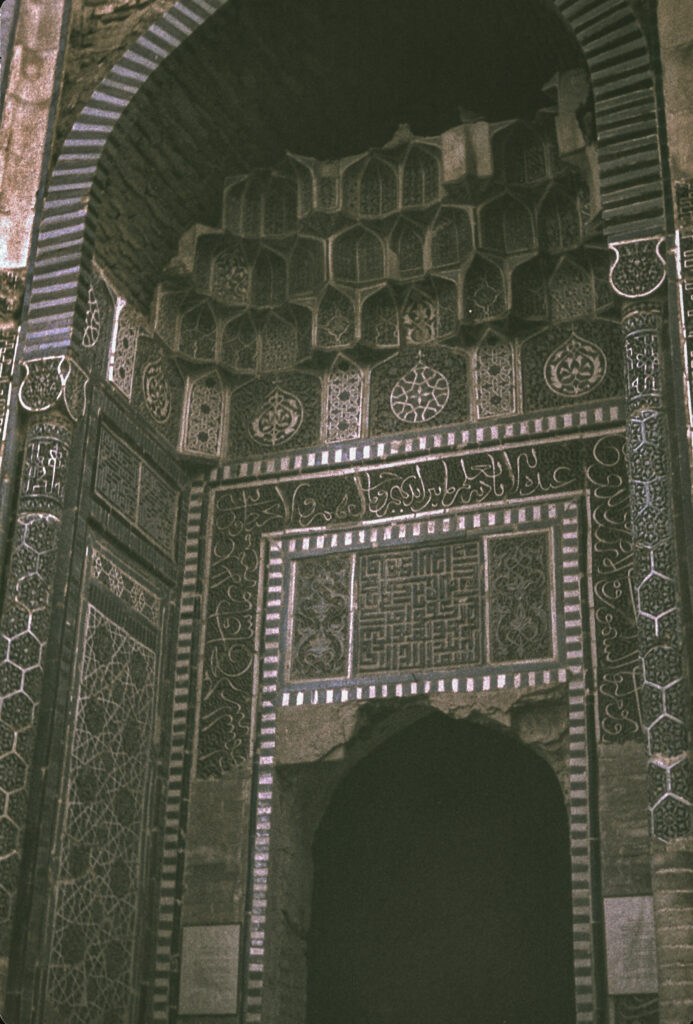

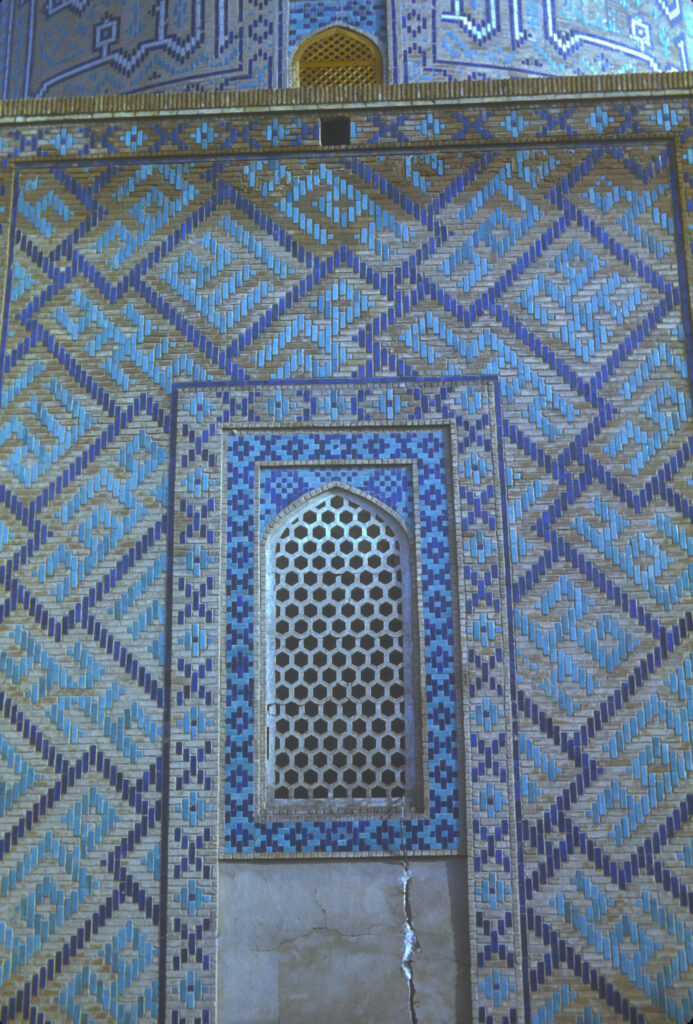

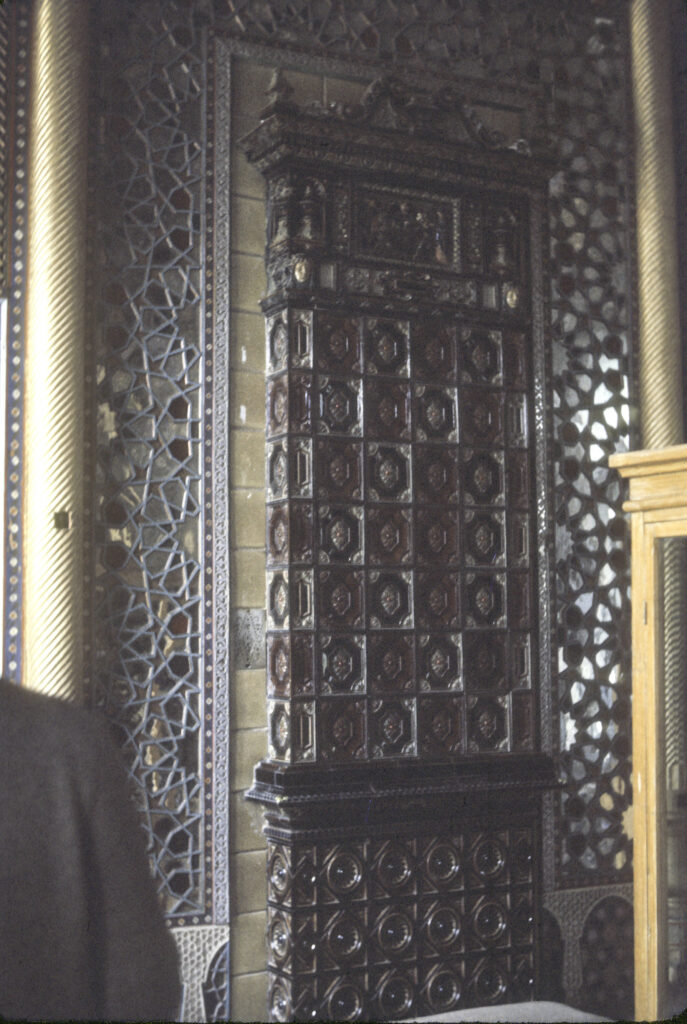

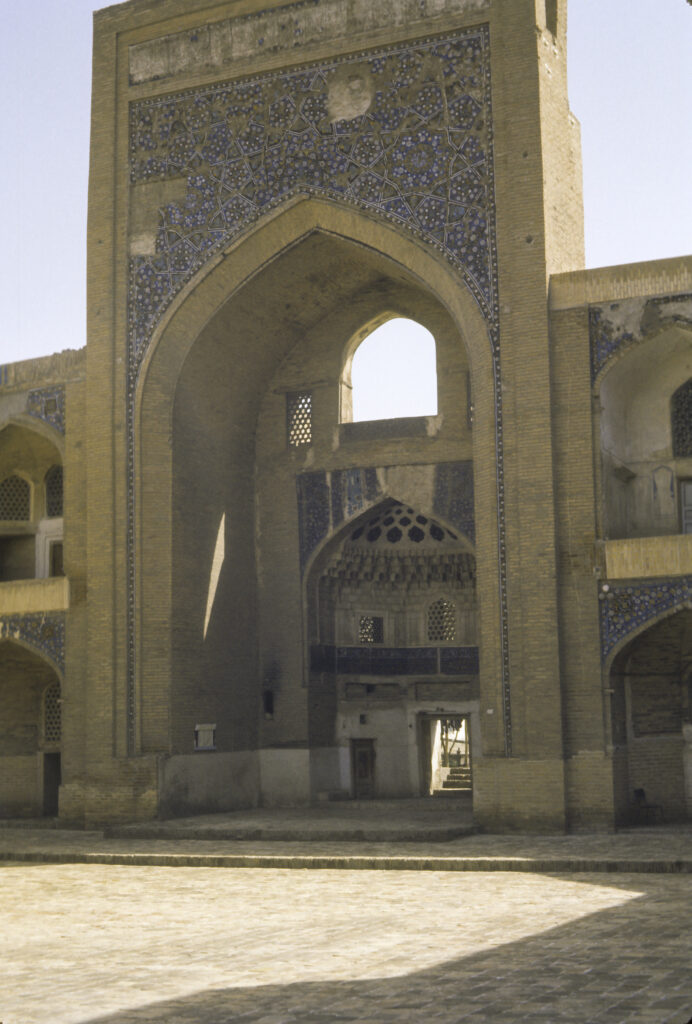

The final and most memorable stop on our itinerary in Tashkent, at least for me, was the Museum of Applied Arts. It was noteworthy not only for the contents of the museum, but even more so because of the building in which it was housed. It was beautifully furnished and decorated, both inside and out. The exterior was remarkable not only for its amazing ganch carvings framing the windows and door, but also, and most unusually, for the Stars of David which appear on either side of the transom above the entrance doorway, as seen in the following photograph.

I don’t recall whether the museum staff told us anything about the history of the house. They may have mentioned that before the 1917 Revolution it belonged to a Russian diplomat, who had it remodeled in a manner reflecting his taste for Asian art and furnishings. But it seemed quite unlikely that a Russian diplomat would have his house decorated with Stars of David, and if the museum staff had any explanation for it, I have long since forgotten. Only recently, when I began the online research for this account, did I come across information which shed some light on the subject. It’s a long and complicated story, though, and may not be of interest to all readers; so before I get into it, let me finish my account of our visit to the Museum of Applied Arts.

When we went inside the Museum, it turned out that the exhibits included not only antiques but also a good deal of recent work by Central Asian artists – ceramics, fabrics, metalwork, leather, etc. – which was of exceptionally high workmanship. Not only that, but the museum staff assured us, the same type and quality were on sale in local shops and bazaars, readily available. This was especially intriguing to many of us as up until then we had seen practically nothing worthy of attention for sale in any of the places we had been so far. Indeed, it was puzzling that the Soviets were missing out on a potentially very lucrative opportunity to pull in some foreign currency by marketing products of native craftsmen as souvenirs. So, after leaving the museum, we spent some of our remaining time in Tashkent scouring the local shops and bazaars in search of the kinds of beautiful and exotic wares we had encountered in the museum.

We were to be bitterly disappointed. I don’t know whether the museum staff was lying to us or whether the types of items on show in the museum were only accessible in stores not accessible to us as student travelers (such stores did indeed exist in the Soviet Union), but most of the merchandise we encountered was junk – inferior stuff, crudely made, perhaps as training exercises by children. However, I did manage to come away with a couple of trinkets that, while not representative of the best craftmanship, at least served as pleasant mementos of the trip. One was a tapestry embroidered with complex geometric designs; it may appear to be hand-made from silk at first glance, but is actually machine-made from artificial fabrics.

The other was a serving platter, made of I don’t know what, with complex lacquered designs including both human and animal as well as geometric figures. I don’t suppose that it is authentic traditional craftsmanship by any means, but it is representative of the better sort of merchandise available in the ordinary bazaars.

Returning to the subject of the museum house, I found several sources online which illuminated its origins. It was originally a private house which belonged to a Russian business magnate, Nikolai Ivanovich Ivanov. Ivanov was an interesting person in his own right, an industrial pioneer who was involved in a variety of industries, including breweries, wineries and distilleries, pharmaceuticals, coal, transportation, etc., in Tashkent and indeed throughout Russian Turkestan. After building himself a new mansion, he sold his old house to a Russian named Alexander Alexandrovich Polovtsev.

But my sources diverge as to who exactly was this Polovtsev. There were two Alexander Alexandrovich Polovtsevs, father and son. The father was a leading figure in the government of Tsar Alexander III and Nicholas II; he served as State Secretary, was a member of the State Council, and one of his areas of responsibility was the overseeing the settlement (of Russians) in Central Asia. (He was also a founder of the Russian Historical Society and served as its chairman from 1879 to 1909.) According to an account by one Arslan Tashpulatovich Jabbarov, writing in the online publication Letters about Tashkent (Письма о Ташкенте), it was he who bought the house. However, another source, an anonymously written article in Wikipedia, ascribes the purchase to the son. Although the Wikipedia article has less depth, I judge it to be more trustworthy, for reasons which will shortly become apparent.

In 1896 Polovtsev arrived in Tashkent on a special assignment from the Ministry of the Interior to study the progress of Russian resettlement in Central Asia and the Caucasus. This must have been Polovtsev Junior, because the father was far too senior an official to undertake such a relatively low-level assignment. But since the task was within his area of responsibility, he would likely have been responsible for selecting the person to be entrusted with it, and an obvious candidate for the job would have been Polovtsev Junior. The younger Polovtsev at some point entered the diplomatic service, and was eventually appointed as Russian Consul-General in Bombay, India; again, this would not be an appropriate assignment for such a highly-placed personage as the elder Polovtsev. My guess is that the latter selected his son for the mission to Central Asia and the Caucasus as a means of cutting his teeth in the diplomatic service, since these areas were in some sense foreign countries, populated by non-Russian, non-Slavic peoples only recently incorporated into the Russian Empire.

In any case, upon arriving in Tashkent, Polovtsev found that he needed an assistant who knew the area, and for this purpose he hired Mikhail Stepanovich Andreev. Andreev was a remarkable figure in his own right; a Russian born in Tashkent, the grandson of a common soldier, he had attended the Tashkent Teachers’ Seminary, the only school where Central Asian languages such as Tadzhik and Uzbek were taught, and had demonstrated considerable aptitude for them. After graduation he soon gained a reputation as a talented linguist, educator and ethnographer and became well-known to local officials, one of whom recommended him to Polovtsev.

Andreev soon became not only indispensable to Polovtsev but his constant companion as well, eventually even accompanying him on diplomatic assignments abroad in Paris and India. Polovtsev was an aesthete, an avid traveler and collector of art, and shared Andreev’s interest in the cultures of Central Asia and the Caucasus. Having become fully conversant with his patron’s preferences, Andreev arranged the purchase of Ivanov’s house, had it remodeled in accordance with Polovtsev’s tastes and sensibilities, and filled it with treasures from Polovtsev’s collections.

The senior Polovtsev died in 1909. According to Jabbarov, just before he died, he donated the house in Tashkent to the municipal government. However, this seems unlikely if in fact the younger Polovstev – who lived on until 1944 – was the actual owner of the house; and indeed, this is affirmed by some of the comments posted on Jabbar’s article in Letters about Tashkent. Moreover one commentator (who identifies himself as “David”), referring to an unspecified archive, states that the “final purchaser” of the house was a Jew from Bukhara, who remodeled it yet again and added not two but six Stars of David. David does not say when the sale took place or why, and the Wikipedia article on the Museum does not mention the sale at all, mentioning only that in World War I the house served as quarters for captured Austro-Hungarian officers, and after the Revolution, having been nationalized, it served as an orphanage until 1937.

It is unclear when and how Andreev’s association with Polovtsev ended—evidently it was over by 1914, when Andreev returned to Turkestan and resumed his earlier career as an educator, taking a position as a regional school administrator in Samarkand. But the Revolution of 1917 opened up new opportunities for him. For many years he had cherished a dream of establishing an institute for the study of Asian languages in Tashkent. In 1918 the new Soviet regime invited him to organize just such an institution, which became the Tashkent Oriental Institute, and eventually the Department of Asian Studies of the Central Asian State University, with Andreev as its chairman.

Like many other leading Soviet scholars, Andreev became the target of Stalinist persecution in the 1930s. He was first arrested in 1933, but was soon released and returned to Tashkent. In 1937 he managed to exert his influence to save the Polovtsev house, which had deteriorated badly during the intervening years, by persuading the authorities to turn it into a museum of Central Asian handicrafts. It underwent restoration on several occasions thereafter, and in 1960 was renamed “Permanent Exhibition of Applied Arts of Uzbekistan.” By the time I visited in 1973, it had been more or less restored to the condition in which its final private owner had left it, with at least two of its Stars of David intact (if the other four had survived, I didn’t see them). In 1997, after being taken over by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Uzbekistan, it was again renamed, this time to “State Museum of Applied Art”.

Andreev was arrested again in 1938, on the accusation of spying for the British. This time he managed to talk his way out of the clutches of the “organs” by convincing the head of the Uzbekistan NKVD that he had important secret information which he had collected for Soviet intelligence while traveling in India and Afghanistan in the 20s. He survived the purges and the war, and was even elected to the Uzbek Academy of Sciences in 1943. But in the postwar period, when Stalin was cracking down again, Andreev transferred to the newly-founded University of Stalinabad (now Dushanbe, the capital of Tadzhikistan), which oddly enough was lacking in Tadzhik language instruction, in order to escape the watchful eyes of the Tashkent NKVD. There, sadly, he was done to death not by the “organs” but by a crazed woman with an axe, whose romantic overtures he had rejected. I should caution that I found this tale of Andreev’s demise only in Jabbar’s not-always-trustworthy account, and not in the Wikipedia articles.

At the end of our stay in Tashkent, we embarked on our first flight on a Soviet jet airliner, which was to carry us to the fabled city of Tbilisi, capital of the Soviet republic of Georgia.