In April, 1973 most of the American IREX students signed up for a trip to Central Asia and the Caucasus. We boarded an Aeroflot IL-18 four-engine turboprop at Domodedovo airport for the first leg of the trip. It was a long, noisy, uncomfortable, boring flight, about 12 hours if I remember correctly. The chicken served as an in-flight dinner really was made of rubber and could not be eaten. The plane shook and rattled its way to Samarkand, where we transferred to an AN-24 twin-engine turboprop headed for Bukhara.

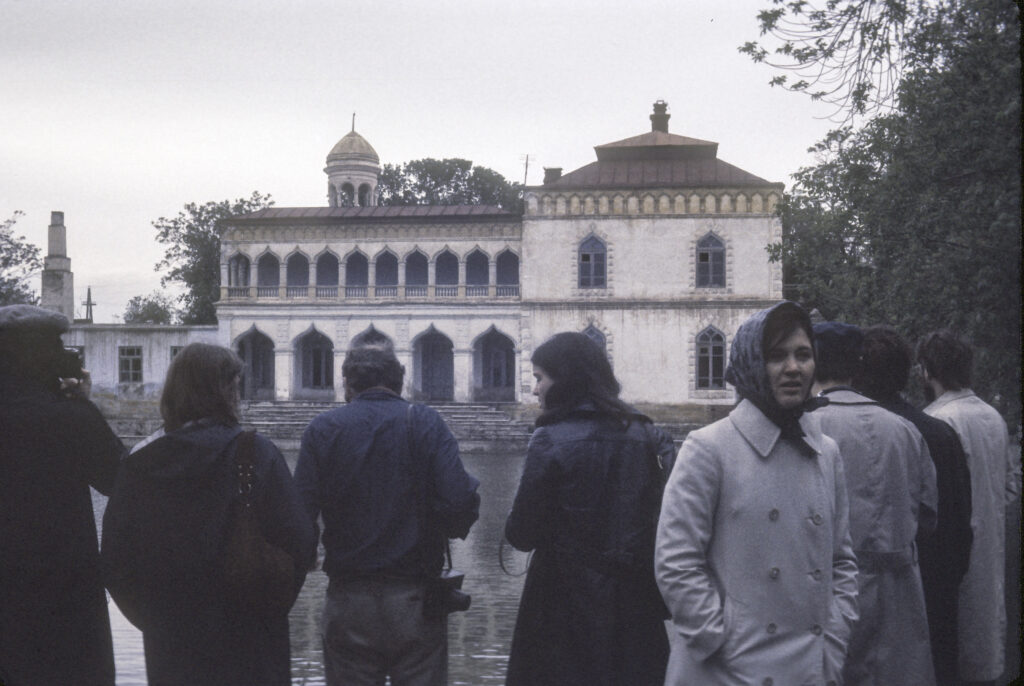

When we arrived in Bukhara, it was rainy and cold. Our first stop, after dropping our luggage off at our hostel, was the Amir’s Palace. The amirs are long gone, of course, the last one having been deposed by the Bolsheviks in 1920. His summer palace, the one we visited, is now a museum.

Bukhara is an ancient city, founded in 500 AD, and for much of its history has been an important outpost of Persian civilization. After the Arab conquest of the Persian Sassanid Empire in the 7th century CE, Bukhara fell under Arab domination for a while, but in the ninth century it became a center of the revival of Iranian language and culture as the capital of the Samanid Empire. In medieval times, as a major stop on the Silk Road, Bukhara profited greatly from the silk trade.

In 1220 it was destroyed by the Mongols. After the Mongol conquests, Central Asia became increasingly dominated by Turkic peoples, and in the 16th century Bukhara became subject to the rule of Turkic Uzbek rulers, who remained in control until the advent of the Russians in the 19th century. In 1873 the Emirate of Bukhara became a Russian protectorate, but continued to remain under the rule of the amirs until 1920.

In 1920, the Red Army invaded and occupied Bukhara, and the People’s Republic of Bukhara was established under its aegis. This lasted until 1925, when Bukhara was incorporated into the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic.

Currently Bukhara is a city of about a quarter of a million people; I do not know how many people were living there when I visited in 1973, but I would guess that the city was somewhat smaller then.

There seems to be some controversy regarding the ethnic composition of the population of Bukhara. Official statistics of the Republic of Uzbekistan, the city’s population is composed of 82% Uzbeks, the majority ethnic group of the country, 6% Russians, 4% Tajiks, and 8% various other ethnic groups. But some sources maintain that the majority of the population actually consists of Tajiks who have been misidentified as Uzbeks for various reasons.

From the Amir’s palace we proceeded next to an old fort on the outskirts of town. This was part of a series of defensive outworks that protected the city before the Russian conquest. Although not particularly interesting, it did provide an opportunity for some fresh air and exercise after our long plane and bus rides.

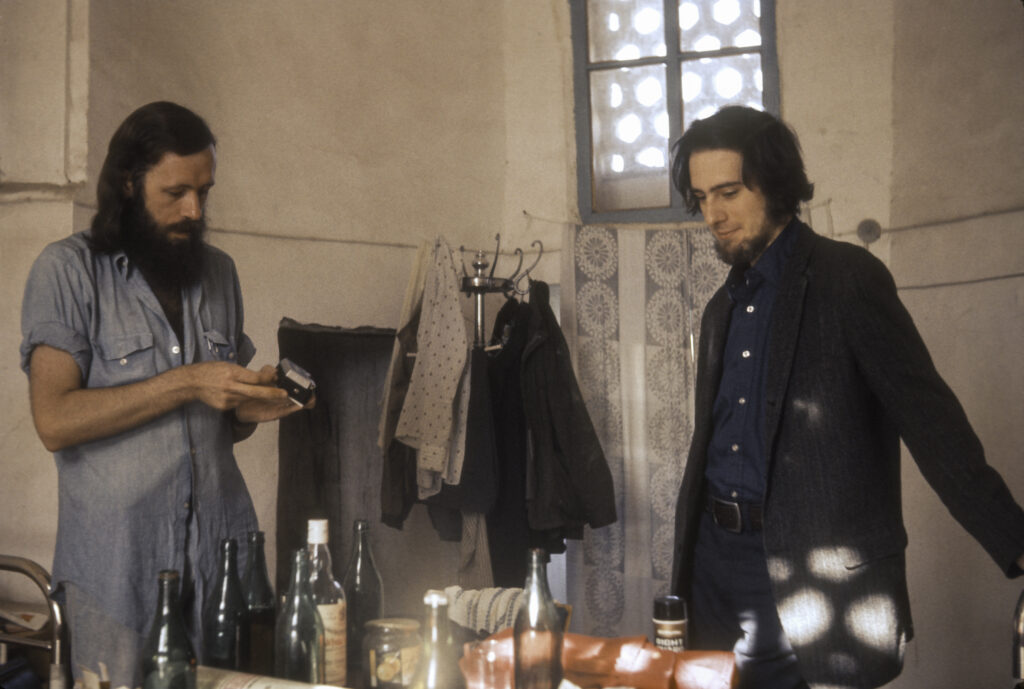

While we scrambled among the ruins, I used the opportunity to snap pictures of some of my fellow-travelers.

During our stay in Bukhara, we were housed in a madrasah, the front part of which is a famous mosque known as Char Minar. One of the most striking structures in Bukhara, the Char Minar has four towers, each with a slightly different decorative motif. On top of the rightmost rear tower perched an odd, irregular structure apparently made of sticks, like a large basket. It turned out that this was a stork’s nest, one of many we would see in the following days.

Adjoining the rear of the mosque was the madrasah, known as the Madrasah of Khalif Niyaz-kul after the wealthy merchant who was responsible for building both in the early 19th century.

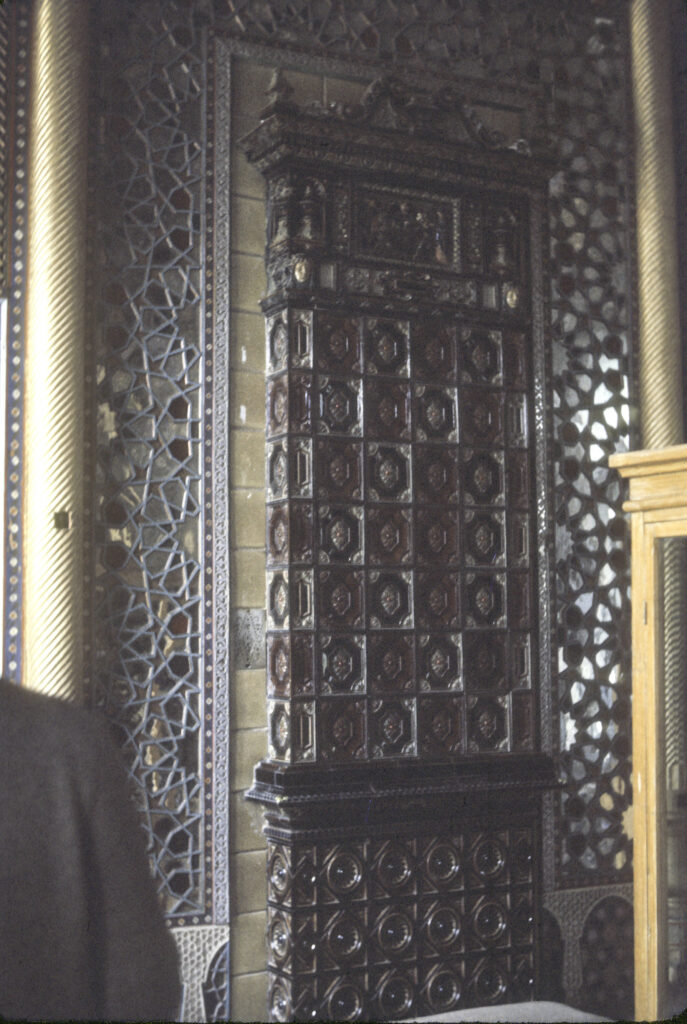

Although a madrasah generally is a school for Islamic instruction, some madrasahs served primarily as hostels, and this was one of them. It was a two-story structure built around a central courtyard, with rooms on both stories.

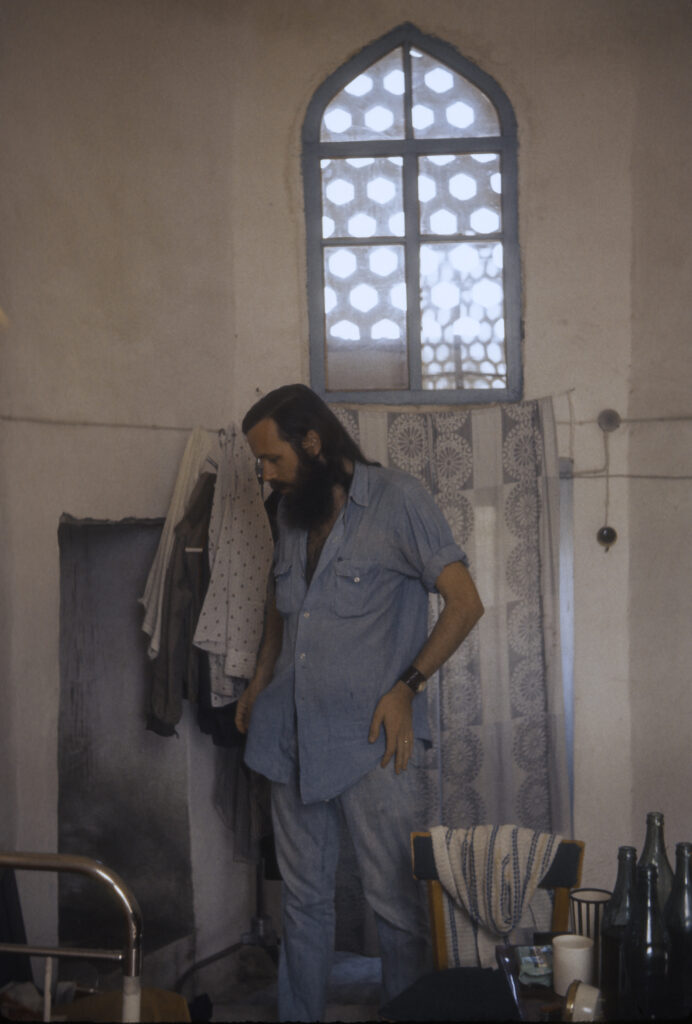

Construction of the structure was extremely solid, and so contrived that the rooms were relatively warm in winter and remained cool in the heat of summer. The quarters were comfortable though rather spartan. We were billeted three to a room.

The hostel’s major shortcoming was the lack of bath or toilet facilities on the premises. There were only public latrines in the otherwise vacant fields next to the madrasah. This was particularly hard on the ladies, who during our excursions kept an eye out for actual toilets. On one occasion they found a school nearby, which they thought would surely have real toilets. They boldly marched into the hallways and found that the school did indeed have toilets, but they had long since fallen into disrepair, were filled with trash and debris and were completely unusable.

To me, the lack of amenities was more than compensated by the opportunity to spend a few nights in a historic architectural treasure.

The city of Bukhara was not large, and most of the major attractions were located near enough to the center that they were accessible by foot. As it turned out, we had lots of time to explore the city unsupervised, providing plenty of opportunity to get into trouble.

Not far from our hostel there was a pond surrounded by an architectural complex known as the Lyab-i-Haus (“by the pond” in Persian), where people gathered to relax and socialize. The pond was the last remaining of several which had existed before the 20th century, but had been found to be vectors of disease and filled in. The Lyab-i Hauz consists of a large 16th-century madrasah, the Kukeldash on the north side, and a smaller 17th-century madrasah and a guest house on the eastern and western sides; on the south is an open area where the locals sat and sipped tea, gossiped and played chess.

Bukhara is home to many architectural treasures, of which the most massive and imposing is the Ark, a great citadel constituting a city within a city. Built on the site of the original settlement, the Ark was in existence at least since 500 CE. According to the great Islamic Persian scholar Avicenna, in medieval times it contained one of the world’s greatest libraries. The library was probably destroyed at the time of the Mongol conquest, along with the Ark and the rest of the city. The Ark was rebuilt, without the library, and survived into modern times; but it was badly damaged when the Red Army assaulted the city in 1920. It had still not been restored at the time of our visit, and was closed to the public, so we were able only to view the exterior. However, I understand that since then it has been reopened and now houses several museums and exhibits.

Opposite the gate of the Ark stands the Bolo Hauz Mosque, the official place of worship of the amirs of Bukhara, built in 1712. Its most noteworthy feature is the carved and painted wood columns holding up the porch roof.

To the west of the Ark lies the Chashma Ayub Mausoleum, built in the 12th century with a peculiar tent-like roof, rare in Central Asia. The name Chashma Ayub means “Job’s Spring,” and legend has it that on this site the biblical Job smote the ground with his staff, causing a spring to gush forth which cured him of his ailments. It was not open when we were there, but nowadays it houses an exhibit devoted to water management in Bukhara.

Nearby the Chashma Ayub was a kolkhoz (collective farm) market where, despite all pretensions to modernity, local farmers sold their produce directly to consumers as they had for centuries.

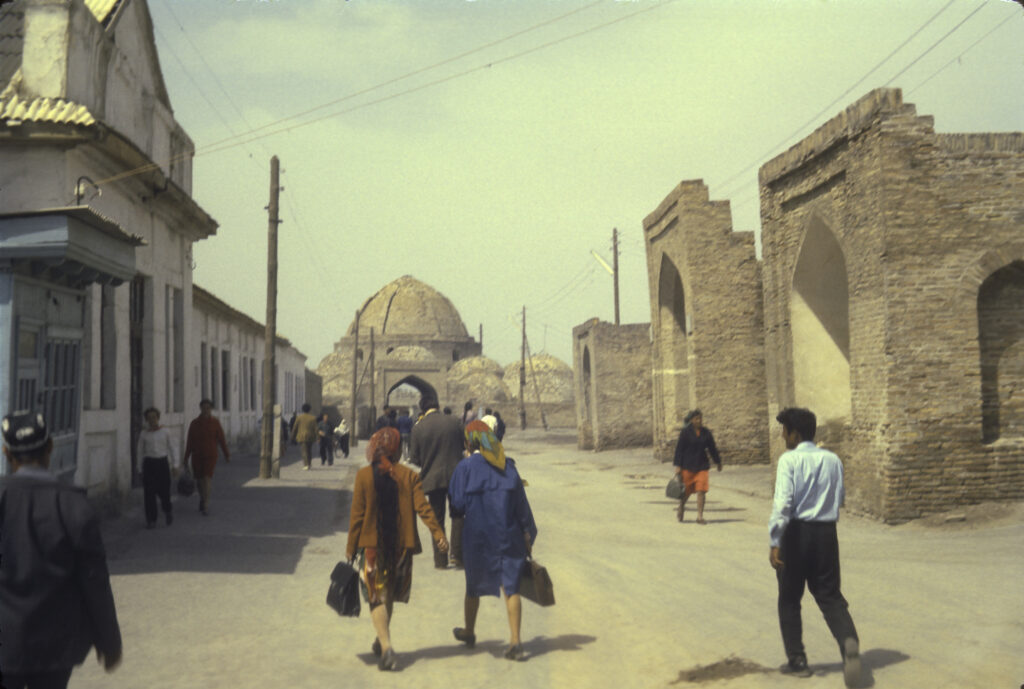

Strolling around the city, we encountered many sharp contrasts between past and present. The city center consisted of broad, spacious streets and boulevards showcasing the architectural masterpieces of the centuries….

…whereas the residential districts featured shabby tenements densely packed in narrow streets.

Mercifully, vehicular traffic seemed to be absent from the old residential districts, since it would have been extremely hazardous to pedestrians, especially children playing in the streets.

However, modern amenities were not entirely lacking. I don’t know what the inhabitants had for sanitary facilities, but at least they had gas for cooking. The gas lines ran overhead along the outside of the houses, supported by tall posts, an arrangement which would probably be considered very hazardous in developed countries, but here there was probably no other option.

I got the impression that basically Bukhara was a quiet provincial town where not much ever happened and there was little excitement or entertainment to be had. Many inhabitants seemed to be hanging around with little to do and the atmosphere was very relaxed, with a few exceptions, which I’ll come to later.

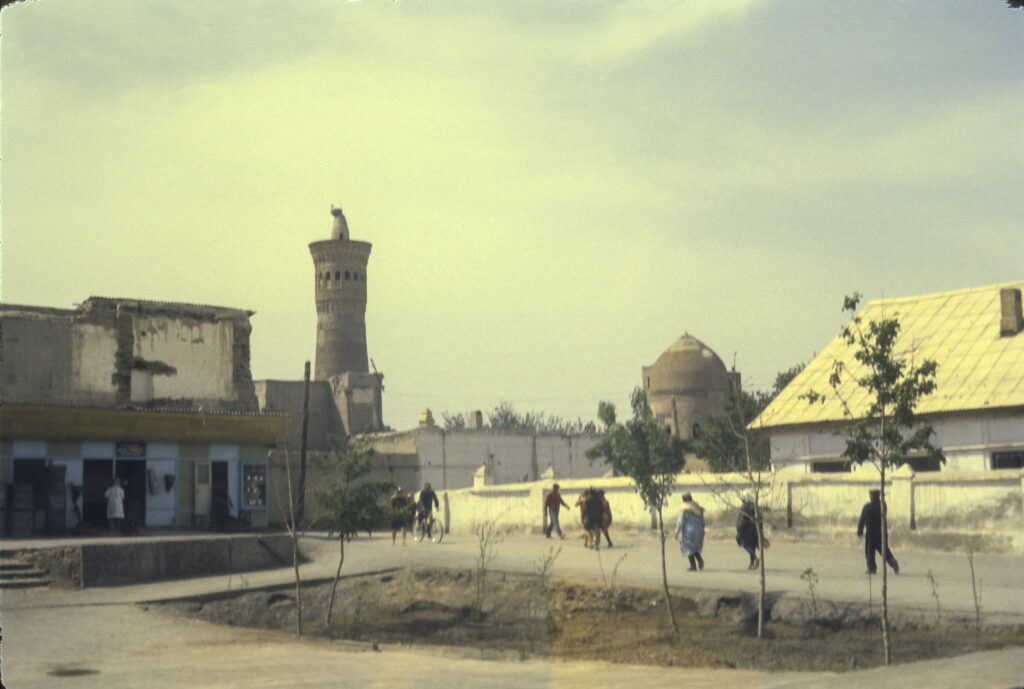

One of the most delightful features of Bukhara, to me, was the abundance of storks’ nests. As a native of California I have never seen storks in the United States; they are mostly found in subtropical areas of the Southeast, but in Europe and Asia they are plentiful. Unfortunately, at the time of year we visited, the storks themselves were absent, not yet having forsaken their winter quarters in the south. But it gave me great pleasure to see their nests in high places all over town, not only in trees but also, most irreverently, on the tops of mosques, madrasahs and minarets.

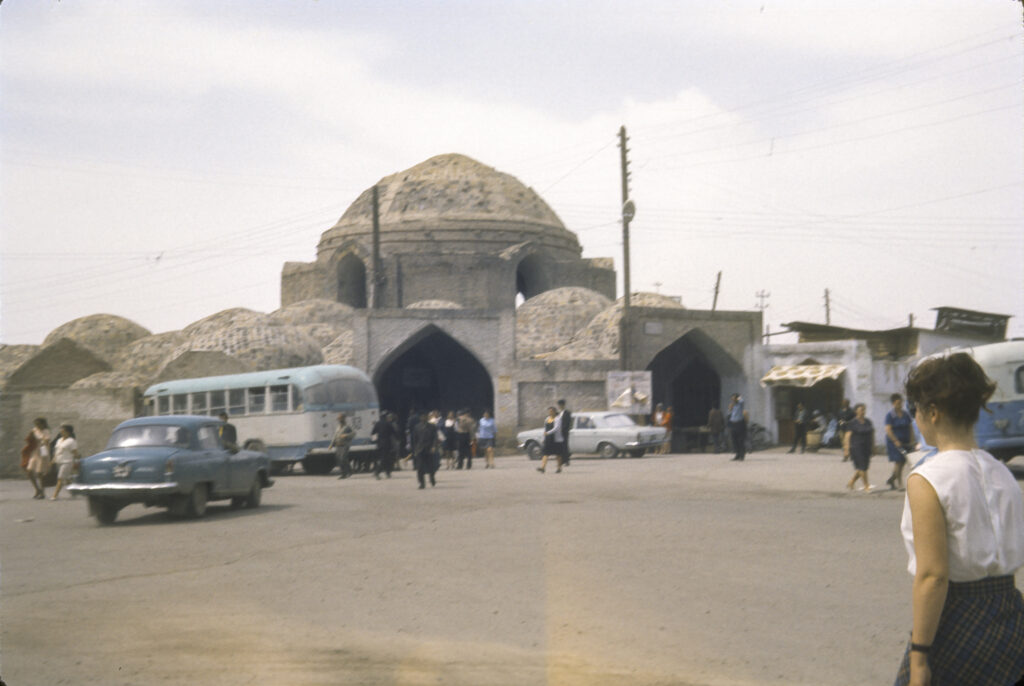

The most lively sector of the city was the central commercial district, in which was located the Tim Abdullah Khan Trading Dome, a market featuring carpets and coffee.

Interestingly, many of the Uzbek women liked to braid their hair in long, thin, twisted braids, much like Afro-American women in the West. In one of the shops, we encountered a man, apparently in his 20s or 30s, who asked us where we were from. People in Bukhara were always asking us where we were from, and some of the group, had taken to responding that we were from Moscow – this was because they had become tired of answering the barrage of questions invariably evoked by a truthful answer, not to mention the inevitable entreaties for handouts which followed. When this particular gentleman received the answer “Iz Moskvy” (From Moscow), he rejoined, “Eto menya ne ystraivaet” (loosely translated, “That’s not what I wanted to hear”). In other words – quite understandably, since we looked like what we were, foreign tourists – he didn’t believe us, and continued to pester us for more information. This sort of thing happened more than once.

The centerpiece of the commercial district was the Toqi Zargaron, an imposing multi-domed structure dating from the 16th century, perhaps the earliest example of an indoor shopping mall I have ever seen.

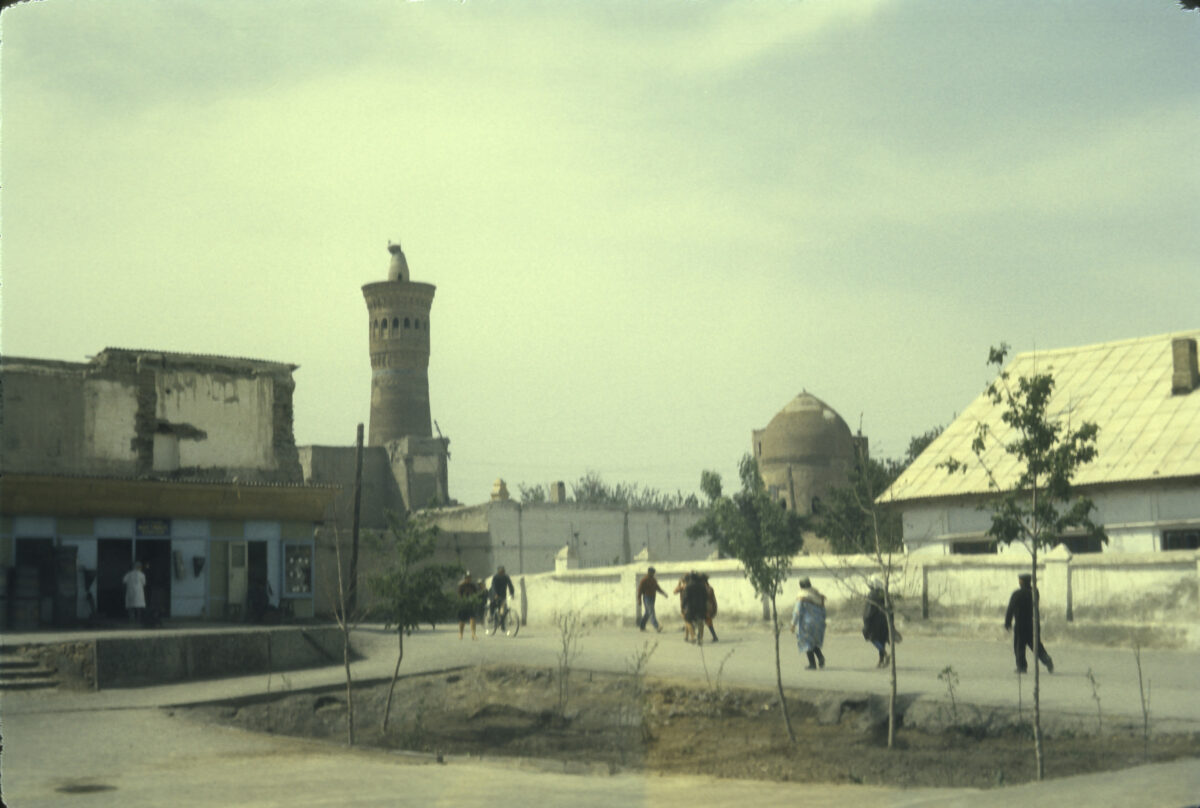

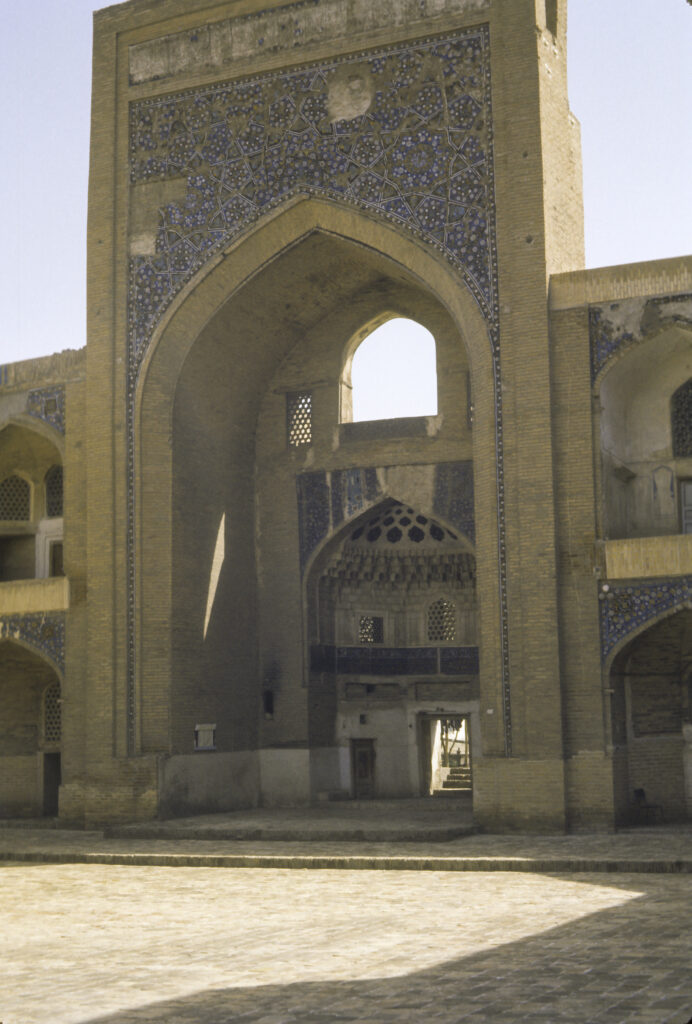

Between our hostel, the Char Minar Madrasah, and the Ark lies the Poi Kalyan (“Great Foundation” in Persian) complex, which hosts some of the most striking architectural gems of Bukhara. From the approaches, as seen in the picture below, it didn’t look too promising, but up close it was quite imposing.

The Poi Kalyan contains three major attractions – the Miri Arab Madrasah, the Kalyan Mosque, and the Kalyan Minaret. If I recall correctly, the Miri Arab was in an early stage of restoration and not open to the public at the time of our visit. The Kalyan Mosque was also undergoing restoration, but was open, or at least so we thought.

“Kalyan” means “great” in Persian and the Mosque, built in the 16th century, was intended to accommodate 10,000 people. In Soviet times it was used as a warehouse and only reopened as a place of worship after the breakup of the USSR in 1991.

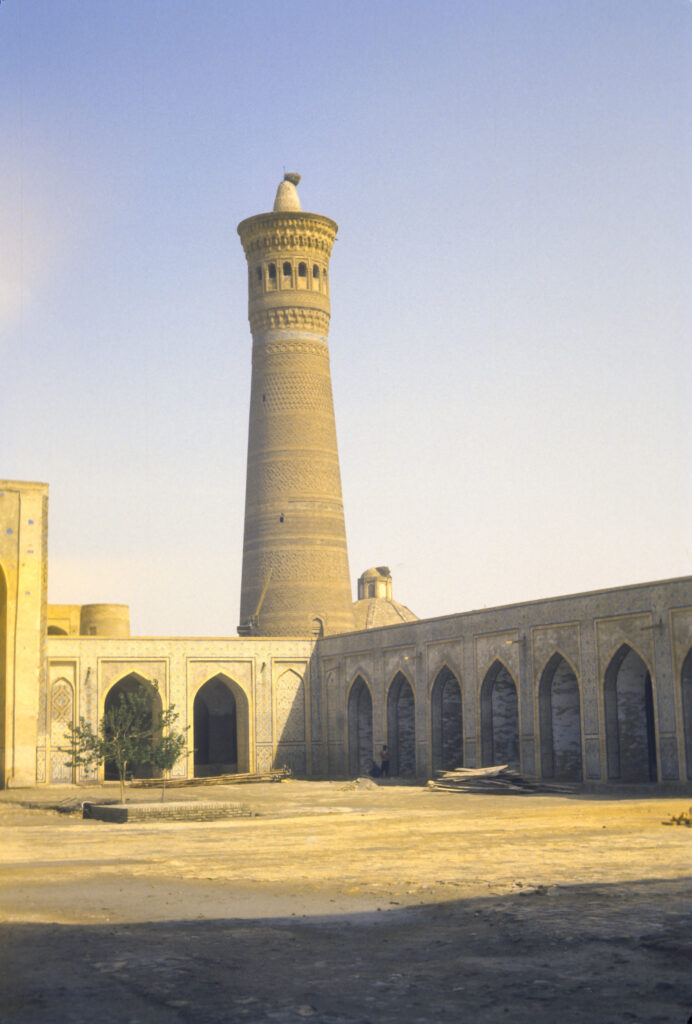

The Kalyan Minaret was built in 1127, during the reign of Arslan Khan, a ruler of the Turkic Karakhanid dynasty, which supplanted the Iranian Samanid rulers in the 11th century. At the time of its construction it was the tallest building in Central Asia, at 47 meters (154 feet) tall. Genghis Khan was said to have been so awed by it that he spared it from the destruction inflicted on the rest of the city. Inside is a spiral staircase with 150 steps, leading to a rotunda with 16 windows, which in turn is surmounted by a “stalactite cornice”, a conical pillar, which inevitably had a stork’s nest on top, giving it somewhat the appearance of a rearing cobra from afar. The Kalyan Minaret is also known as the Tower of Death, because according to legend criminals were executed by being thrown off the top.

The Kalyan Mosque and Minaret very nearly became the scene of grief for some of our party, too. Five of us, of which I was one, entered the courtyard of the mosque, and while we were checking it out, three of us decided that it would be fun to climb to the top of the minaret. I refrained from doing so, as did one other of our group, Jerman Rose, because I knew what would happen. Jerman and I continued to snoop around the mosque while the others made the ascent. A while later, when the three making the climb didn’t return, Jerman and I went to the entrance to the minaret staircase, where we heard shouting and banging on the door. It turned out that someone had barred the door from outside, preventing them from getting out of the minaret. Fortunately there was no lock, and Jerman and I simply unbarred the door so that they could escape. As we exited the mosque we encountered an old man, looking very much like the one in the next picture, who was muttering curses and imprecations and threatening to call the police. He was the one who had barred the door, and evidently, even though the mosque was not then functioning as a place of worship, he evidently considered it a sacrilege for infidels to be violating its precincts. We didn’t wait to find out whether we were indeed violating some local ordinance or other, and hastily evacuated the area.

Back in our rooms in the Char Minar, we packed up and waited on the benches for the bus to take us to the airport and begin the next stage of our odyssey, to the fabled city of Samarkand.