Samarkand, our second stop in Central Asia, is another Silk Road city in existence since time immemorial, i.e. the 8th or 7th century BCE. It first entered history as the capital of the Sogdian satrapy (province) of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and was conquered by Alexander the Great in 329 BCE. Thereafter it was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkish rulers until 1220 BCE, when it fell to the Mongols of Genghis Khan. After Genghis Khan’s death, his empire became divided up into semi-autonomous, and later independent, khanates such as the Golden Horde in Russia, the Ilkhanate of Persia, and the Chagatai Khanate (named after Genghis Khan’s second son, its first ruler), which extended from the Aral Sea to the borders of China, and included the cities of Bokhara and Samarkand.

But Samarkand is indelibly associated with the name of one of history’s most formidable conquerors, Timur the Lame or Tamerlane, under whom Samarkand reached the apex of its glory. Timur reunited the lands of the Golden Horde, the Ilkhanate and the Chagatai Khanate, devastated large areas of the Middle East, and was on his way to invade China when he died in 1405. He was notorious for leaving huge pyramids of skulls on the sites of the cities he conquered, and his campaigns are estimated to have caused the deaths of around 17 million people, about 5% of the world’s population at the time.

Born in relatively modest circumstances near Samarkand sometime in the 1320s, Timur first rose to prominence as a general under the Chagatai khans, rose in their service, and eventually turned the Khan into a puppet ruler before casting off the pretense and assuming power in his own name. By 1370 he had made Samarkand his capital and begun a construction program aiming at making it the wonder of the world.

Timur’s last and most ambitious project, the Bibi-Khanym mosque, was constructed from 1399-1405, ostensibly in memory of the mother of his wife. Beyond that, his intent was not only to create a mosque which would be one of the largest and most magnificent in the world, but also to host the entire male population of Samarkand, a city of 150,000, for Friday prayers.

The Bibi-Khanym Mosque enclosed an area 167 meters (548 feet) long and 107 meters (358 feet) wide, oriented northeast by southwest (conforming to the Qibia, i.e. direction of Mecca). No less than eight minarets graced the perimeter.

Entering from the northeast via a vast parade portal, 35 meters (115 feet) high, one found oneself in a great courtyard, at the other end of which stood the massive main iwan. An iwan is a feature of traditional Persian architecture described as “a rectangular hall or space, usually vaulted, walled on three sides, with one end entirely open,” and a formal gateway called a pishtaq, or projecting portal. Beyond the main iwan was the main dome, which was not visible from the courtyard.

The sides of the courtyard were framed by two smaller iwans, each with its own dome. In the center of the courtyard was a massive stone stand which was designed to hold a very large Koran.

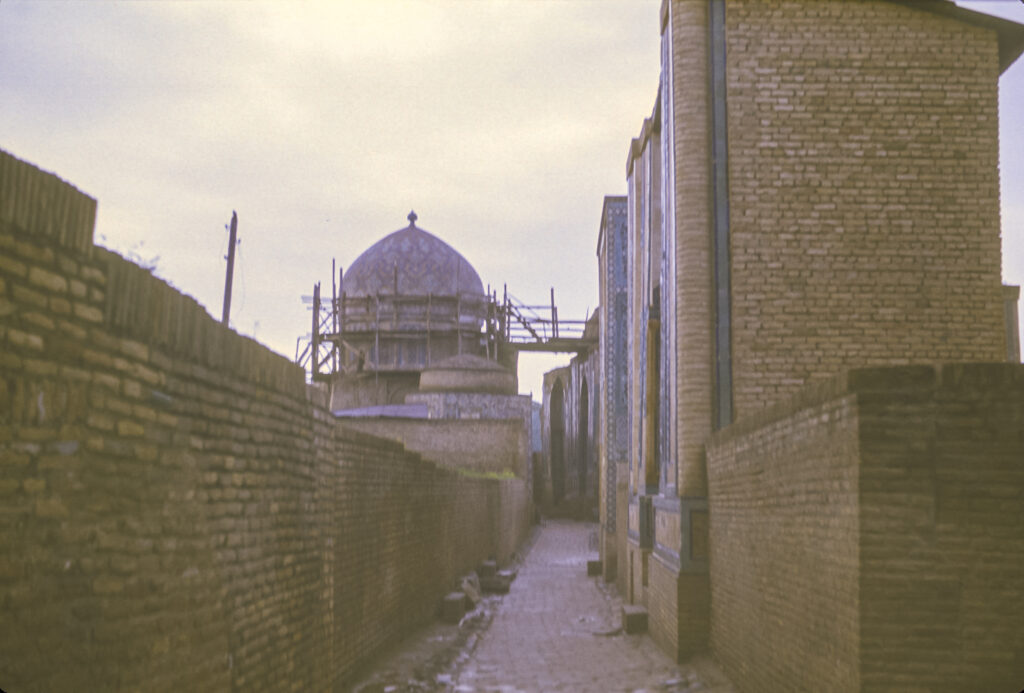

Unfortunately, Timur’s specifications for construction of the mosque exceeded the technological capabilities of his architects and engineers, and right from the day of its completion the mosque began to fall apart, with bricks falling out of the main dome.

Timur’s successors made attempts to repair and reinforce the mosque, but by the the 16th century the Timurid dynasty had been replaced by the Shaybanids, ruling from Bukhara, and they evinced little interest in maintaining the monuments of Samarkand. The Bibi-Khanym continued to deteriorate, and for centuries the local inhabitants plundered it for building materials. In 1897 a great earthquake demolished much of what was left. At the time I visited in 1973, it was in sorry shape, but at least some scaffolding had been erected to retard the continuing disintegration of the main iwan.

Restoration efforts began in the 1970s, gained momentum after Uzbekistan became fully independent in 1991, and continue down to the present. From what I can gather the exterior of the mosque has regained much of its original appearance.

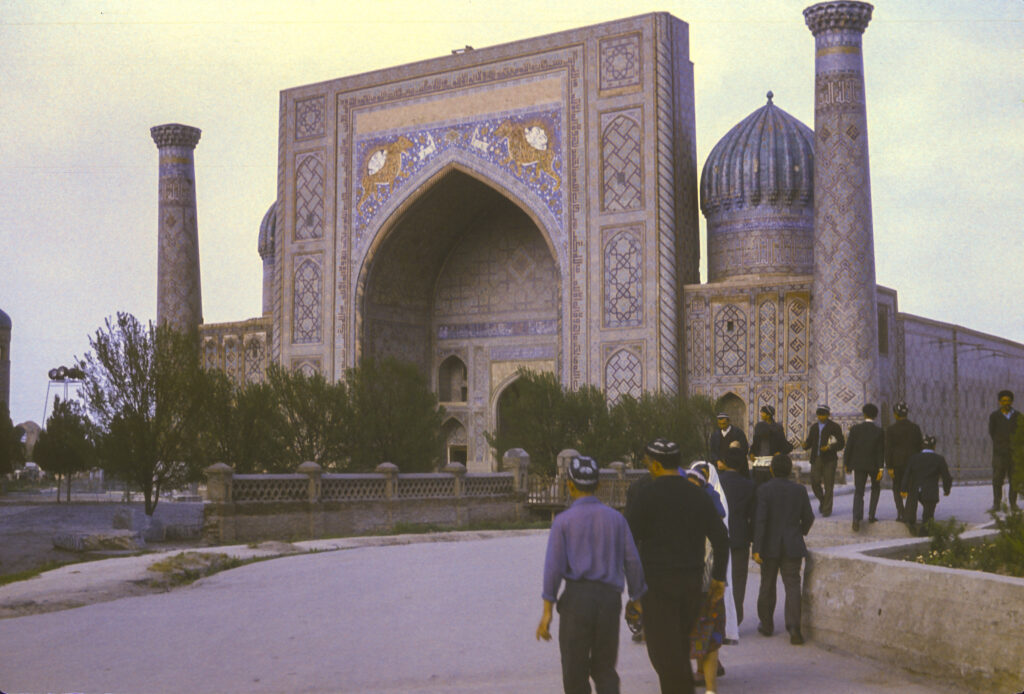

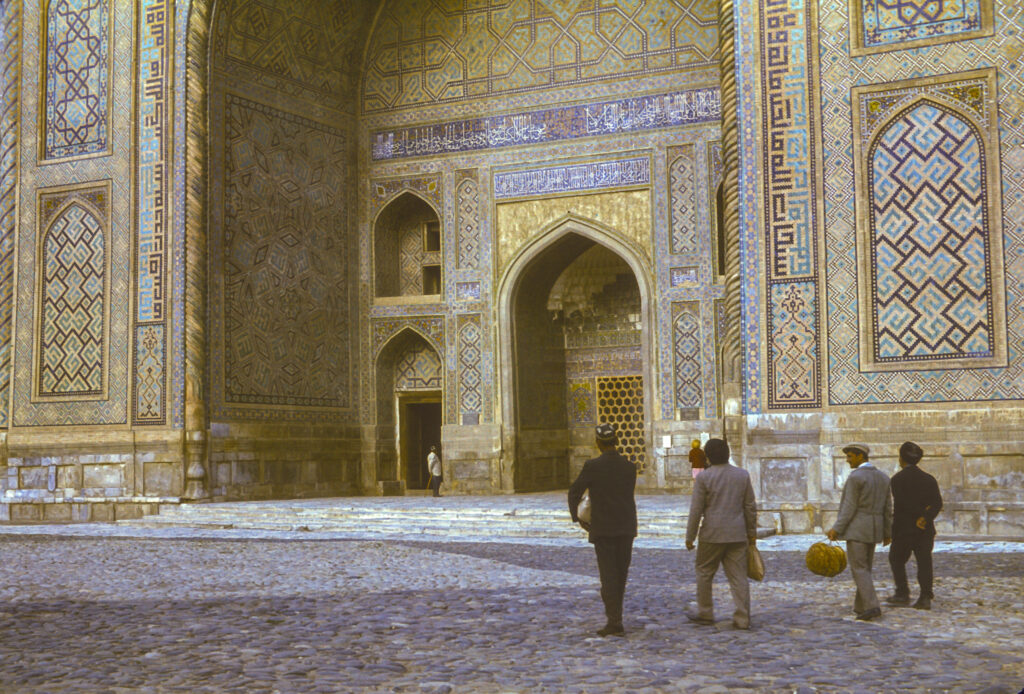

Our next stop in Samarkand was Registan Square, the heart of old Samarkand, which is bounded by three great madrasas: the Ulugh Beg, the Tilya-Kori, and the Sher-Dor. If I recall correctly, the first two were in early stages of restoration and covered in scaffolding, so our attention focused mainly on the third.

After Timur’s death in 1405, his son and successor, Shah Rukh, moved the capital of the Timurid Empire to Herat, in modern-day Afghanistan, and left Samarkand in charge of his son Ulugh Beg, who set about to make Samarkand the intellectual and cultural center of the Timurid Empire. He built the madrasah which bears his name in 1417-1420 and invited some of the foremost scholars and intellectuals of the Islamic world to teach there, especially astronomers and mathematicians.

In the 17th century the then ruler of Samarkand, Amir Yalangtush Bakhodur, ordered the construction of the Sher-Dor Madrasah on the east side of Registan Square, opposite the Ulugh Beg Madrasah. Construction began in 1619 and was completed in 1636. Ten years later work began on the Tilya-Kori Madrasah, which was completed in 1660.

The Sher-Dor Madrasah is very similar in exterior appearance to the Ulugh-Beg Madrasah, but there are some important differences. Both have enormous Persian-style facades and are flanked by flat-topped minarets, but the Sher-Dor has two large domes, one on either side of the facade, which are absent from the Ulugh Beg. Also, whereas the Ulugh Beg facade is adorned with orthodox Islamic geometrical figures, the Sher-Dor facade flouts the Islamic prohibition against depicting living creatures, with mosaics depicting tigers and other animals on the facade.

The animal mosaics may represent some late Persian Mithraic or Zoroastrian influence.

Critics consider the architecture of the Sher-Dor represents a degenerate form by comparison with the “golden age” of the fifteenth century, as embodied in the Ulugh-beg Madrassah, but it is still impressive.

The third of the great Registan Square madrasahs is the Tilya-Kori, which as already mentioned was undergoing restoration and closed to the public. It stood on the north side of the square and had a somewhat different plan from its neighbors. It still had an iwan-type facade, but the corner towers of the structure were not as tall and the building plan was asymmetric. It served as both a mosque and a residential college for students; the mosque section was on the west side and was crowned with a dome. The name Tilya-Kori means “gilded”, and the interior of the mosque was abundantly covered with gold.

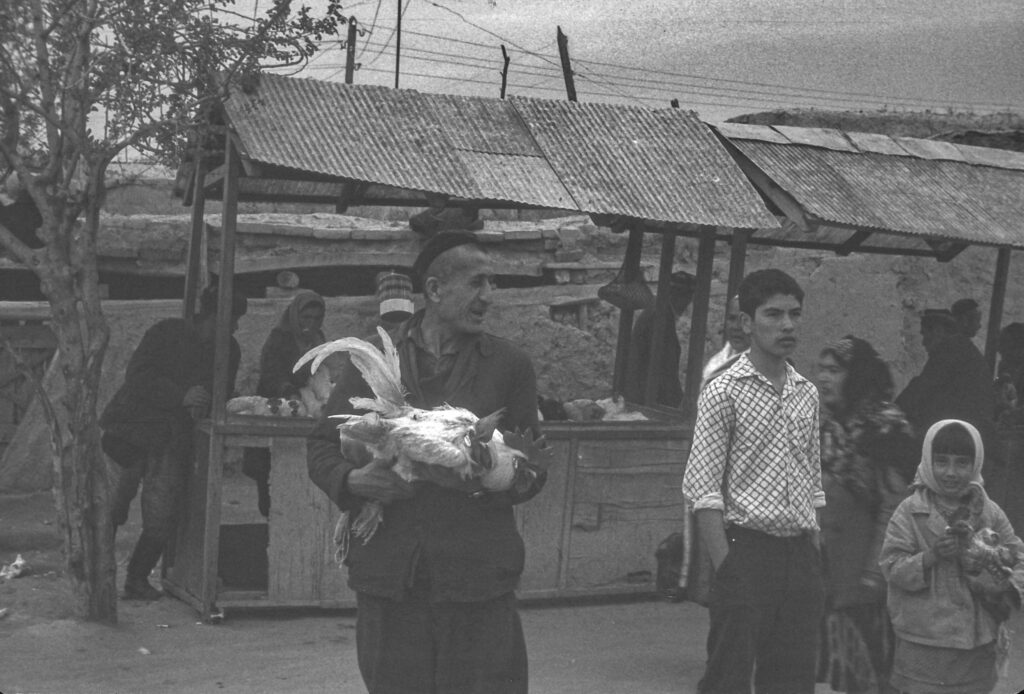

We did not have as much time to stroll around the residential areas of Samarkand as we did in Bukhara; I have the impression that the city seemed a little more prosperous than Bukhara.

On one of the several days we spent in Samarkand, we visited the observatory built by Timur’s grandson Ulugh-Beg in 1428. Ulugh-Beg had become interested in astronomy at an early age after visiting the famous Maragheh Observatory of Persia, built in 1259 under the patronage of the Mongol Ilkan Hulagu; and he is said to have modeled his observatory on the Maragheh.

Ulugh Beg’s observatory of course was unable to benefit from using telescopes, which would only be invented nearly two hundred years later. Astronomers of the fifteenth century had to make do with other instruments, such as the sextant, a device for measuring the altitude of a celestial object above the horizon. The centerpiece of Ulugh Beg’s observatory was the giant Fakhri sextant, which was used to make very exact measurements of transit altitudes of stars, from which their precise coordinates in the sky could be calculated. Ulugh Beg used these measurements to compile a catalog of stars and their locations which was far in advance of anything previously available.

The Fakhri sextant was constructed with one segment and a supporting structure above ground, and the rest underground. Only the latter part has survived. In 1447 Ulugh Beg’s father, Shah Rukh, died, and in the ensuing struggle for succession Ulugh Beg was defeated and dethroned by his own son, who subsequently had him assassinated. His scientific activities had aroused the enmity of Islamic obscurantists, who after his death succeeded in having his observatory dismantled. It was only rediscovered in 1908.

Shah-i-Zinda, on the northeast of Samarkand, is a necropolis, a complex of tombs and mausoleums. The name means “the living king” and is associated with a cousin of the prophet Muhammad who supposedly came with Arab invaders in the 7th century CE to convert the population of Samarkand to Islam and was beheaded by the locals for his trouble. The legend has it that he did not die but instead escaped into a well, where he has lived ever since. Eventually, in the 11th century a shrine was eventually erected over the well, initiating the development of the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis. The complex continued to expand thereafter, with the most important additions occurring in the 14th and 15th centuries under the Timurids.

About 1435 Ulugh-Beg had a monumental main entrance gate to the ensemble built. A tradition now somewhat in doubt holds that he also commissioned a large two-domed mausoleum for the scientist and astronomer Qazizadeh Rumi, the first director of his observatory.

Entering the complex from the south, through the grand archway, after passing by the Qazizadeh Rumi mausoleum, one comes to a stone staircase leading to another archway. Beyond that is a group of mausolea in part associated with the female relatives of Timur, in particular his sister, Shad-i Mulk Aga, and his niece, Shirin Biqa Aga. There is also the Tughlu Tekin mausoleum, built by a friend of Timur for his mother, and the Amirzadeh mausoleum, built in 1386 by an unidentified party.

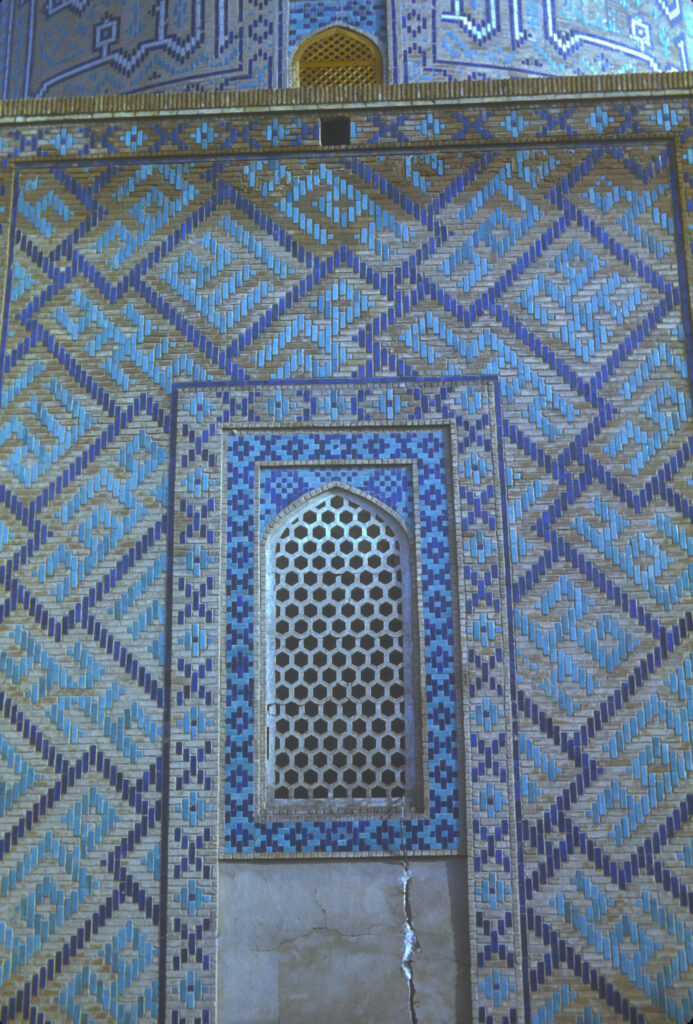

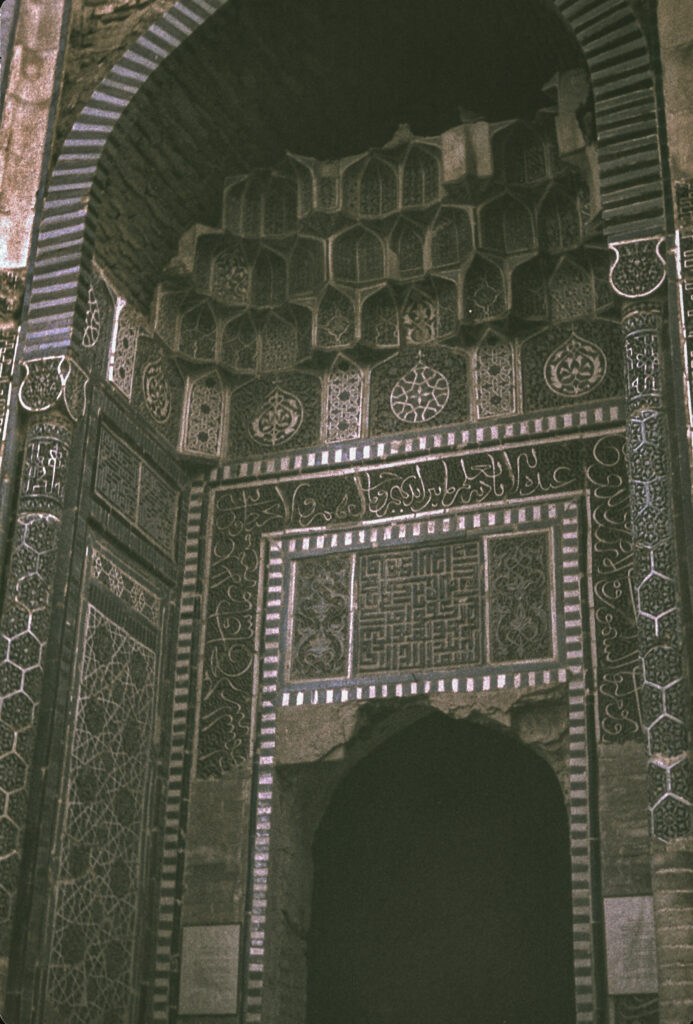

Here, in the middle group, one first encounters the incredible tilework that I found to be the most memorable feature of the Shah-i-Zinda complex.

Particularly striking to me were the deep-relief inscriptions featuring verses from the Koran and other sacred texts; from what I can gather, these were produced by applying dozens of layers of lacquer and then carving through the layers. This must have required an astounding level of skill and a great deal of expenditure to pay for it; it seems to have flourished mainly in the era of the Timurids, i.e. mid-14th – early 15th centuries, and some have found evidence of Chinese influence in it.

I have not been able to ascertain who commissioned the Amirzadeh Mausoleum or who is buried in it, but an inscription on the front dates its construction to 1386. It is also known as the Octahedron, because of the eight-sided structure on which the dome rests.

The Shad-i Mulk Mausoleum, built for the sister of Timur, was perhaps the best-preserved structure in the complex, with exquisite terracotta tile in and around the archway, including some of the deep-relief Koranic embedded inscriptions.

A close examination of the facade of the Shad-i Mulk Aqa reinforced my initial impression – this was tilework of unsurpassed artistry and craftsmanship.

Located at the north end of the complex are the oldest structures, including the Khwaja Ahmad Mausoleum, an anonymous mausoleum of 1361 possibly built for one of Timur’s first wives, Qutlugh Ata, and others, most notably the shrine of Qutham ibn Abbas. Unfortunately, I do not have any surviving photos of the shrine; I also don’t have any photos of the interiors of any of the structures, because my camera was not equipped with a flash. I don’t remember whether any of the buildings were open to go inside when I was there.

The Khwaja Ahmad Mausoleum, not to be confused with the Mausoleum of Khwaja Ahmad Yasawi in Kazakhstan, was built in the 1340s, and closes off the north end of the Shah-i-Zinda complex. Although the interior was said to be in ruins (we didn’t get a look at it), the exterior featured some of the most original and outstanding tilework in the complex.

In particular, one of the outstanding examples of the deep-relief calligraphic tile in the Shah-i-Zinda complex decorates the facade of the Khwaja Ahmad Mausoleum.

The 1361 Qutlugh Ata Mausoleum was especially noteworthy for the muqarna over its doorway. An archetypal feature of Islamic architecture, a muqarna is an ornamental vault, a self-supporting arched honeycomb form intended to provide a smooth, decorative transition from a wall to a ceiling and thus enliven what would otherwise be a bare, uninteresting space.

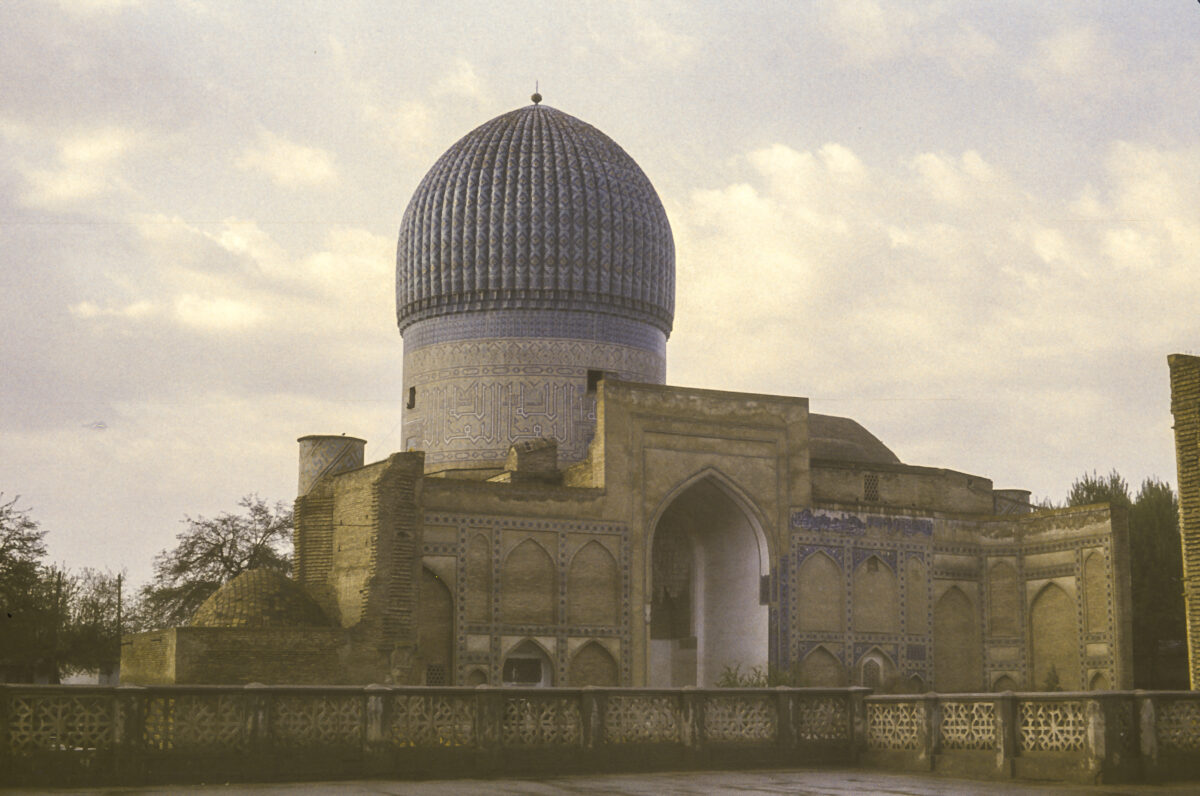

Our final stop in Samarkand was Gur-i-Amir, the mausoleum of Timur. It is a monumental work, well-preserved, visible from afar, and the model for many subsequent tombs, such as the Taj Mahal.

Gur-e Amir contains not only the tomb of Tamerlane, but also those of his sons and grandsons. Timur had originally built a smaller tomb for himself in his native city of Shahrisabz, south of Samarkand, and he began Gur-e Amir as a tomb for his grandson and heir apparent Muhammad Sultan, who predeceased him in 1403. However, when Timur himself died in 1405, Shahrisabz was inaccessible because the passes to it were blocked with snow, so he was buried in Gur-e Amir instead. Later, his other grandson Ulugh Beg made Gur-e Amir the family crypt, and Timur’s sons Miran Shah and Shah Rukh were buried there, as well as Ulugh Beg himself.

Like the other monuments of Samarkand, the Gur-e Amir fell into disrepair once the glory days of Samarkand were over. However, it was the first of the major structures to undergo restoration; the Soviets government undertook some early efforts in that direction just before the war with Germany began in 1941, as we shall shortly see, and after the war work began in earnest, with much being accomplished in the 1950s and after. Thus, by the time I visited in 1973, Gur-e Amir was in a much better state of preservation than most of the other monuments of Samarkand, and it was a glorious sight indeed.

Timur’s tomb was engraved with two inscriptions. One read “When I Rise From the Dead, The World Shall Tremble”; the other, “Whosoever Disturbs My Tomb Will Unleash an Invader More Terrible than I’. In June, 1941, an expedition led by Soviet scientist Tashmuhammed Kari-Niyazov began excavations in Gur-e Amir and on June 20, 1941, the excavators opened the tomb of Timur. On June 22, Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

Supposedly, after a month or two of horrific reverses Joseph Stalin started to believe in the curse and ordered the remains of Timur reburied, which was done in December 1942. Legend also has it that Stalin ordered a plane to fly over the front lines at Stalingrad for a month with the remains of Timur, and that the Muslim soldiers fighting there with the Red Army were fully informed of this to stimulate their zeal for fighting the Germans. In January 1943, the German Sixth Army surrendered, giving the Soviets the victory in one of the decisive battles of history.

All of this, of course, is coincidence. World War II began in 1939 with the invasion of Poland; Hitler had always intended to destroy the Soviet Union, and began planning the invasion in 1940. I am not in a position either to verify or refute the legend about the plane flying over the Stalingrad battlefield with the remains of Timur, but I am certain of one thing: even though the exhumation of Tamerlane’s remains did not “unleash” him, and even though he lost in the end, Hitler was indeed a more terrible conqueror than Tamerlane. If indeed Timur was responsible for the deaths of 17 million people, he was still no match for Hitler, who accounted for far more than that. Also, Timur sponsored the creation of some wonderful masterpieces of art and architecture. Hitler only caused destruction and ruin.