The Russian Summer School class at the Institute in Munich began in early June, forcing me to miss my college graduation ceremony on June 12 (not that I cared about that), and was supposed to last until about the middle of July, when we were to leave for the USSR. At least that was the plan. Actually, as I’ll explain in another post, things worked out somewhat differently. Nevertheless, I had time to see the major landmarks in Munich, and to capture them on film.

The Institute for the Study of the USSR

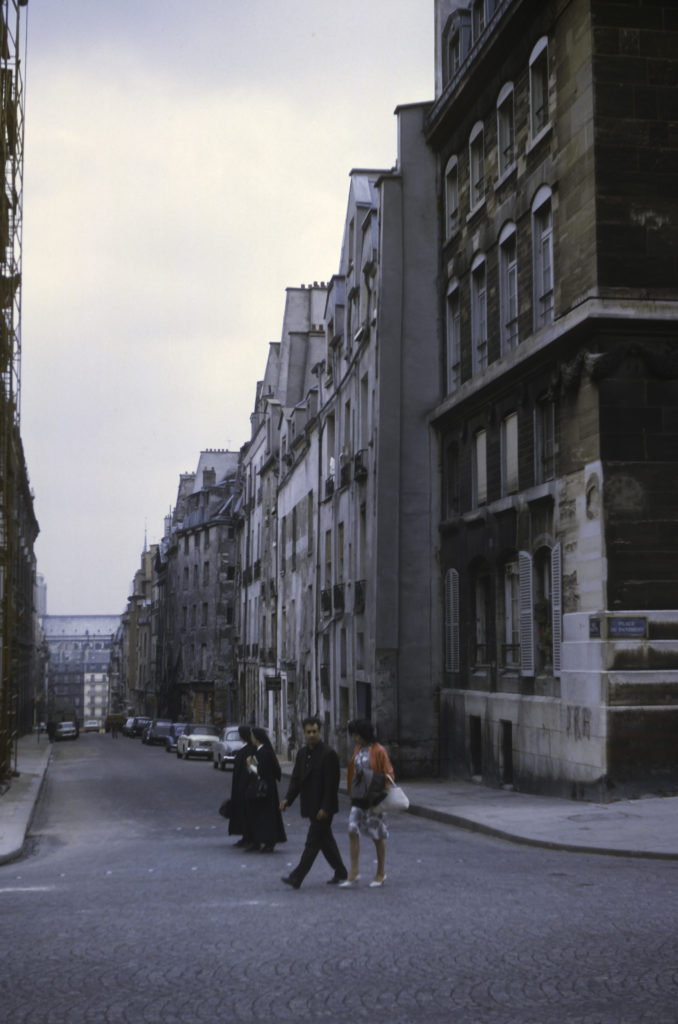

This was a CIA front, a subsidiary of Radio Liberty, which broadcast American propaganda into the USSR. It existed from 1951 to 1972, when the US Congress cut off its funding, though support for Radio Liberty continued. Staff consisted largely of Soviet emigre scholars. Its headquarters was located on Mannhardtstrasse in Munich. I’m not actually sure whether I took the following photo on Mannhardtstrasse, but it does give you an idea of what the place looked like, since all the streets in that local looked very similar.

Lodgings

A number of us were quartered in a pension (rooming house) down by the Isar River, which flows through the middle of Munich. It was a very pleasant area, the rooms were small but adequate, and the proprietor, Frau Burge, was an efficient German hausfrau who kept the place neat and spiffy. The only thing I didn’t like about the rooms were the beds, or rather what was on them. Here I was introduced to duvets, heavy quilts which to my mind were not at all appropriate for summer; under a duvet I was hot and sweaty and found it hard to sleep.

The neighborhood was quite pleasant, with the Isar River right across the street from the pension, and it was a great area to start my career as a travel photographer.

The Isar River

Wandering the banks of the Isar was a good way to start seeing Munich. The riverside is quite picturesque, lined with parks and historical sites.

St. Luke’s is a Lutheran church in a historically a Catholic city where Protestants were generally unwelcome until the 19th century. It was built in the 1890s and is the largest Protestant church in Munich. It is a very imposing church, with a central dome is almost 64 meters (209 feet) high and two secondary towers that are little less tall. The architecture is a combination of Romanesque and Gothic; the architect chose these styles with the express purpose of conforming to the local traditions and catering to the preferences of the Catholic rulers.

The Isar is, improbably, the birthplace of surfing in Germany. This came about in the 1970s, long after I was there, so I did not see any of it myself. It mostly happens at the Eisbach, near the English Garden, somewhat upstream of the location in the picture below, which was taken near the pension where we were staying. The salient feature of this photo is the weir – a low dam built to raise the upstream height of the river and regulate its flow. There was also a Fischentreppe – a “fish stairway” to allow fish to bypass the weir and prevent them from being trapped on the upstream side, but it is not visible in this picture. In the background is the Maximiliansbrücke (Maximilian Bridge), named after Maximilian II, King of Bavaria from 1848 to 1864.

Continuing along the banks of the Isar, I came to a park called Maximiliansanlagen, and eventually to the monument shown below, which is the Friedensengel, the Angel of Peace. Originally built to commemorate the 25 years of peace following the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-71, it was completed in 1899 and is located on Prinzregentenstrasse (Prince-Regent Street), where it crosses the Isar on the Luitpoldbrücke. The gilded bronze figure atop the 82-foot column is modeled after a statue of Nike, the Greek goddess of victory, unearthed by German archaeologists at the Temple of Zeus in Olympia in 1875. In 1981 the statue fell off the column and was damaged, but it was subsequently repaired and replaced on top of the column in 1983.

Further up along the Isar, and after crossing the river, I finally arrived at the English Garden, an enormous (900-acre) park on the Isar River, which, as already noted, is famous for river surfing, and also for naked sunbathing. It also holds a structure called the Monopteros, which is a Grecian-style bandstand located on an artificial hill, another product of King Ludwig I’s building spree in the 19th century.

The vast open fields of the English Garden also provide a nice view of downtown Munich, as seen in the photo following. The twin towers at the center of the picture belong to the Frauenkirche (“Cathedral of Our Lady”) , the largest and most famous church in Munich. Built in the fifteenth century, it is the seat of the Archbishop of Munich and Freising and holds the tombs of a number of members of the Wittelsbach dynasty, the rulers of Bavaria from medieval down to modern times. For some reason I never took a proper picture of it while I was in Munich, but thanks to municipal restrictions on the height of buildings, it remains the tallest building in town and is visible from a long way off, dominating the city skyline.

Heading west toward the city center from the English Garden, I came across another famous Munich monument, the Siegestor, (“Victory Gate”). Initially commissioned by King Ludwig I (Bavaria was an independent principality until the formation of the German Empire in 1871), the Siegestor was completed in 1852 and was dedicated to the glory of the Bavarian Army. It was heavily damaged in World War II and only partially restored by the time I saw it in 1964. The inscription above the arches reads “Dem Sieg geweiht, vom Krieg zerstört, zum Frieden mahnend, “Dedicated to victory, destroyed by war, urging peace”. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I only shot the back side of the Siegestor, not the front. Originally the Siegestor had statues on top; in the early 21st century the monument was more fully restored and the statues with it.

Just south of the Siegestor, on Ludwigstrasse, is the academic center of Munich, where one finds the University, formally titled the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich, and the Bavarian State Library. Next to the Library is another of the major Catholic churches of Munich, name of (surprise!) St. Ludwig’s. Constructed in the neo-Romanesque style and completed in 1844, St. Ludwig’s proved to be quite influential, serving as a model for numerous other churches, synagogues and even secular buildings, especially in America. It also contains a number of frescoes by the famous German painter Peter von Cornelius, one of which, depicting the Last Judgment, claims to be the second largest altar fresco in the world – 62 feet high by 38 feet wide.

The University Area

Near the University I came upon a couple of French art students hoping to sell their oeuvres to passers-by on the street. I didn’t have enough Deutschmarks with me to purchase any of them, so I wished them well and went on my way.

Continuing south down Ludwigstrasse, I came to Odeonsplatz, the site of the Feldherrnhalle (“Hall of Field Marshals”). This is a 19th century monument commissioned by King Ludwig I and dedicated to the Bavarian Army. The statue on the left side of the monument is of Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, the commander of the forces of the Catholic League (of which Bavaria was a member) in the early years of the Thirty Years’ War. He won a series of great victories against the Protestant forces in the early years of the war, but he was not a Bavarian – he was originally from the Netherlands, and spent many years in the service of the Spanish trying to suppress the Dutch Revolt before coming to fight the Protestants in Germany. The statue on the right is of Karl Philipp Josef, Prince von Wrede, who was thus honored for being a leader in the German resistance against Napoleon in the early 19th century. However, though he was indeed a Bavarian, and the leading Bavarian soldier of his day, the distinction is dubious; at first he fought for Napoleon, and even led the Bavarian contingent in the French invasion of Russia in 1812; after the debacle in Russia, Bavaria switched sides and fought against the French, but Napoleon badly mauled Wrede’s troops at the Battle of Hanau in 1813.

The sculptural group in the center of the Feldherrnhalle was added in 1892 to commemorate the German victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the subsequent unification of Germany.

When the Nazis staged the abortive Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, they marched from the Bürgerbräukeller to the Odeonsplatz, where they had a brief gun battle with the Bavarian State Police, leaving 4 policemen and 14 marchers dead. The coup was suppressed and Adolf Hitler was convicted of treason and sentenced to five years in prison, of which he served only nine months. Later, after Hitler took power in 1933, the Nazis turned the Feldherrnhalle into a monument to the members killed in the Putsch, and used the Odeonsplatz for rallies and ceremonies in which new members of the SS were sworn in. After World War II, the Feldherrnhalle was restored to its pre-Nazi condition. But right-wing groups still occasionally try to use it as a venue for rallies and demonstrations.

Not far from the Odeonsplatz, on Max-Joseph-Platz, stands the Bavarian State Opera House, opened in 1818. The statue in front of the Opera House is a memorial to Maximilian I Joseph, King of Bavaria from 1806 to 1825. Beneath the square there is an underground garage, and if I remember correctly, the Munich subway system was under construction at the time I was there, which would account for the work site in front of the monument.

A couple blocks south of the Opera House stands the world’s most famous beer hall, the Hofbräuhaus. Founded in 1589, the Hofbräuhaus was originally a brewery; it was remodeled into a beer hall in 1897, when the brewery was relocated to the suburbs. In 1919, just after the end of World War I, it became the headquarters of the short-lived Bavarian Communist government in 1919. It was not the scene of the abortive Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 – that dubious honor belongs to another beer hall, the Bürgerbräukeller, which no longer exists – but the Nazi Party did hold a number of its early organizational meetings in the Hofbräuhaus. It was bombed heavily during World War II, but was rebuilt afterward and fully restored by 1958, long before my arrival. Besides Adolf Hitler, famous or infamous patrons and visitors across the centuries include Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Mikhail Gorbachev, Louis Armstrong, Thomas Wolfe, John F. Kennedy and George H. W. Bush.

At this point, I found myself at the very center of Munich. It was a crowded, bustling area in 1964, and I doubt that it is any less so today.

In Marienplatz, the central city square, stands the New City Council building – in German, Neues Rathaus (there is also an Old City Council building, as we’ll see shortly). (I always thought that the word “Rathaus” was most appropriate to the seat of municipal government in English as well as in German.) The Neues Rathaus is a neo-Gothic building constructed during the 19th century. The tower balcony houses the famous Glockenspiel: Three times a day, at 11 AM, 12 PM and 5 PM, little clockwork figures emerge from the tower and chase each other round and round on two levels.

The Neues Rathaus is also adorned with sculptures and reliefs depicting various real and legendary figures, including most of the rulers of the city from its founder, Henry the Lion, and the Wittelsbach line of dukes and kings, as well as the allegorical slaying of the dragon in the picture below.

Looking away from the Neues Rathaus to the east, one sees the Mariensäule, a 68-foot column with a statue of the Virgin Mary on top; the Old Town Council House (Altes Rathaus) at left, with spires; and the Church of the Holy Ghost (with white tower, at right). The Altes Rathaus, unlike the Neues Rathaus, is indeed old, dating from the fourteenth century.

From Marienplatz, I turned west and strolled to Karlsplatz, known locally as Stachus, another major plaza in downtown Munich. It was named after Karl Theodor, Duke and Elector of Bavaria from 1777 to 1799. However, the Bavarians detested Karl Theodor and celebrated joyously when he died, and ever since they have called the square Stachus, after an old pub that previously existed there. Karlsplatz is the site of a Gothic-style gate (seen at the left of the picture below), which was part of the medieval fortifications of the city and had been known for centuries as the Neuhauser Tor until Karlsplatz was built. Judging from photos I have seen recently, the appearance of the area has changed quite a bit since 1964; there is now a fountain in front of the Karlstor, and an ice-skating rink operates there in wintertime.

Not far from Karlsplatz/Stachus is Lenbachplatz, site of the Wittelsbacherbrünnen, a monumental fountain in neoclassical style dating from the 1890s. The fountain’s design celebrates the elemental force of water: the horseman tossing a boulder, on the left side of the fountain, depicts water’s destructive power, and on the right, the woman seated on a bull, holding a bowl, symbolizes water’s healing qualities.

This modernistic tower on Pacellistrasse, just east of Lenbachplatz, caught my eye; it appears to be an elevator for the building next to it, which happens to be the Amtsgericht, the Munich Municipal Court.

Somewhere in my Munich wanderings, I encountered this Baroque-appearing structure, which I have not been able yet to identify. A sign nearby said “Prinz-Carl-Palais,” but that name actually belongs to a Neoclassicist mansion – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prinz-Carl-Palais.

Munich is a city of many fountains – we have already encountered the Wittelsbacher Fountain on Lenbachplatz – but the one I liked best, probably because of the naked woman in the middle, is the Fortuna, which I encountered in Isartorplatz, on my way back to my pension from downtown Munich.