Although I came from a Navy family – both my biological father and my stepfather had served in the Navy

I wasn’t wrong. On September 19, 1964, I reported to Naval Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island, was assigned to Juliet Company, taken to the barracks and given a bunk. Next morning before dawn I was roused out of bed by the Voice of Doom. It belonged to a Southerner named Hollin (we called him Howlin’), who along with others proceeded to make my life a living hell for the next month. (Life at OCS only got a little better after the first month, but at least by then we were used to it.)

It was immediately apparent that my apprehensions about lacking military aptitude were well-founded. Like the traditional military academies, Annapolis and West Point, discipline at OCS was enforced by a system of demerits, known colloquially as “gigs”. As an officer candidate, you had to carry in your back pocket a form known as a “7-Alfa.” At any moment, an officer – either a student officer or a real one – could order you to hand him a 7A and write you up for any offense, real or imagined. Gigs were then assigned based on the severity of the offense. Your military grade was rated on how many gigs you got. You could get gigs for failing to salute, for any discrepancies in your appearance, for forgetting to ask permission to speak – anything imaginable, and some things that weren’t imaginable. I got plenty of gigs.

One of an officer candidate’s duties was to stand the midnight watch in the barracks, which involved staying up all night to watch out for fires, natural disasters, spies, enemy attacks, etc. – and most important of all, waking up the company officers in advance of reveille at dawn We took turns standing midwatches. It turned out that my turn to stand the midwatch came on the night scheduled for the transition from daylight savings to standard time – in those days it came in October. This of course meant that I had to spend an extra hour on watch. I suspect that whoever was responsible for scheduling watches assigned me this night on purpose, because I was the least-liked person in my section. Whatever the case, I did indeed somehow manage to bugger it up. When the time came to wake up the company officers, I made the rounds dutifully, but somehow one of the wakees, I forget his name, showed up late, mumbling something about “the goddamn midwatch didn’t wake me up.” Not being able to prove him wrong, or even given a chance to revisit the issue, I got 7 gigs for that.

I’m not kidding when I said I was the least-esteemed person in my section. (Companies were divided into four sections – these corresponded to grades in a school. Each month one section graduated and another was admitted.) At the end of the first month peer ratings were conducted. Ostensibly a method of rating one another’s suitability for leadership, these were actually more like popularity contests. I was right at the bottom in the peer ratings. I was considered gauche, error-prone and excessively nervous (all true). However, the peer ratings did not take into account performance in the classroom, which was not widely shared among the officer candidates; in that I was above average, though not at the top.

The hierarchy of command at OCS at the company level was topped by the Company Officer, an actual commissioned officer, usually a lieutenant, assisted by a Company Chief Petty Officer (CPO). Beneath him were the company’s student officers. Each section had a permanent Section Leader, an Assistant Section Leader and various other functionaries. Our Company Officer was Lieutenant J. W. Johnson, who was a mustang, an officer who had come up through the enlisted ranks. He was a good ol’ boy from Florida, coarse and rough-edged, a bear of a man with a stentorian voice, whose entire education beyond high school had been in the Navy. Some of the OCs, especially the ones from the South, considered this to be scandalous, and complained about not enough college-educated officers not being assigned to OCS. This was unfair. LT Johnson may have been uneducated, but he was smarter than most of his critics. The same whiners also looked askance at our navigation instructor, who happened to be African-American. He was an intelligent and highly educated person, and a capable teacher, but that cut no ice with the malcontents, who called him “Snowball.” I should hasten to add that not all the malcontents were from the South. One of them, Richey G. Hope, who happened to be from Illinois – in fact he was the nephew of Otto Kerner, a onetime Governor of Illinois – lamented that he had never before had to work under a black man and the Navy shouldn’t put one over him. LT Johnson, who as I already mentioned was from Florida, for this and other reasons didn’t take much of a shine to Richey G. Hope. He pulled a 7A on Hope, gave him 75 gigs and rolled him back three months. I don’t know whether Richey G. Hope ever graduated from OCS. But LT Johnson wasn’t the last mustang I encountered in the Navy. In the course of my three years of active duty after graduating from OCS, I served with, and mostly under, a number of them. A few were jerks, but most were extremely competent officers and convivial people.

One outstanding example was Charles J. Duchock, our Section Leader. Chuck Duchock was also a Southerner, from Birmingham, Alabama. He said Birmingham was a good place to be from – FAR from. Chuck had come to OCS via the Navy Enlisted Scientific Education (NESEP) program. Sailors who qualified for the NESEP program were assigned to one of 22 universities, with all expenses paid for up to four years, after which they were offered an unrestricted line commission in the Navy. Prior to going into the NESEP program, Chuck had been in the submarine service, and intended to go back to it after OCS. He was not a typical Southerner. For one thing, he was Catholic (Polish by descent; in Polish the name would be spelled Duczok.) He recounted that when he became engaged to be married in Birmingham, his fiancée, a Protestant, was told by her family that she would have to sleep with a priest before the wedding to prove that she would make a good Catholic. Chuck Duchock was superb as a section leader, and I’m sure he went on to a successful career in the Navy. I know he at least made Commander, and was given command of the submarine rescue ship USS Pigeon in 1978.

Chuck’s room was right across the hall from mine. I remember that one time, after a hard day of work and study, I dozed off at my desk while reading a publication classified as Confidential. We had had it ground into us that we were to guard classified pubs with our lives and it would be the end of a career for anyone who lost track of a classified publication. (Confidential was the lowest level of classified-ness, the others being Secret and Top Secret.) I admittedly had kind of a cavalier attitude toward Confidential publications because my dad often had them around the house when we lived on the Philadelphia Naval Base. Chuck was determined to teach me a lesson. He sneaked into the room and delicately lifted the classified pubs off my desk without alerting me. When I woke up and couldn’t find them, I came unglued. I couldn’t understand how it happened, and I thought it was the end of my naval career. Chuck let me stew for a while and then gave back the pubs, to the accompaniment of severe admonitions. I guess I must have learned the lesson well, since I later enjoyed a successful run as Cryptocustodian and Top Secret Control Officer at NAVFAC San Nicolas Island. Chuck didn’t pull a 7A on me as someone less charitable might have done; he was a good guy.

I didn’t always get on well with my roommate, Assistant Section Leader Franzini, who was my roommate. Jim Franzini was a graduate of Penn State University. He had been to OCS on a previous occasion and had bilged out, to which there was no shame attached – it had been much more difficult then. (Sometime in the year before my arrival, after someone with influential relatives had committed suicide, the Navy had introduced reforms which made OCS a much less trying experience.) Franzini had served a year as an enlisted man, then reapplied for OCS, and this time he made it through with flying colors. But his first encounter with OCS had traumatized him, and he was a little insecure about it. I suspect he was worried that my proximity to him as a klutzy and ill-favored roommate would make him look bad and jeopardize his standing. He fears were not groundless, since his duties as Assistant Section Leader kept him busy and he had to rely on me to keep our room clean and neat. In the beginning he was always ragging on me for my shortcomings, assuring me that I would blow it and flunk out. But in the end he came around. Upon graduation he was assigned to Naval Intelligence in Bremerhaven, Germany, an assignment which I would have loved to get. To my considerable annoyance, despite my background with Russian and Soviet studies, the Navy did not even consider sending me to the Defense Language School in Monterey. I think the Navy used the “dart-board” method of figuring out where to assign OCS graduates.

In order to provide some leadership training in preparation for our future responsibilities, each officer candidate was given a shot at being “Section Leader of the Day” (abbreviated SLOD). This mainly consisted of marching the section from one classroom to another during breaks. Loudspeakers piped marching music from a tape player (“Waltzing Matilda” was a favorite piece) to keep us in step. It was the responsibility of the SLOD to make sure that the tape player was restarted when the tape ran out. Inevitably, when my turn came to be SLOD, I didn’t notice that the music had stopped and didn’t reset the tape. I forget how many gigs I got for that.

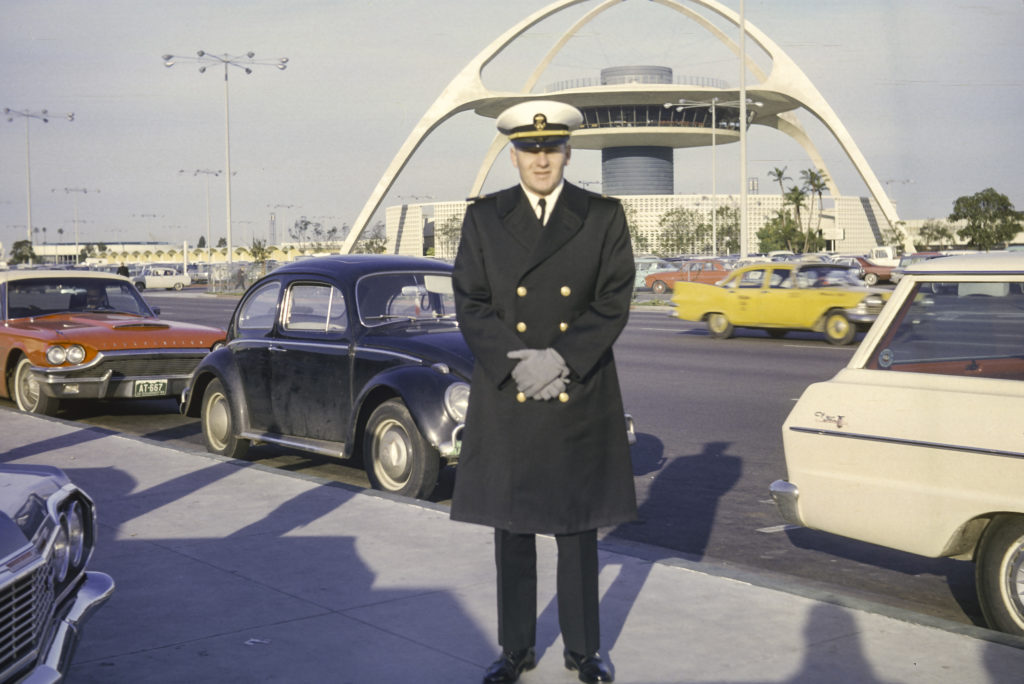

My most grievous transgression, however, came in the last month of OCS, which was January 1965. The Navy sent us home for two weeks Christmas vacation, just like civilian schools. It hadn’t snowed much to speak of before Christmas, but on New Year’s Day, just before we were scheduled to return, a huge blizzard hit and shut down the entire northeastern USA. It was over by the time I boarded the plane at LAX for the return trip to OCS, but when I got back to Newport, everyone was still digging out. All the barracks had been shut down for vacation, and the heating system with them; it was a relic of a bygone age, it took a day or two to get it restarted and unfreeze the pipes, and in the meantime we froze. To speed up the process, the command ordered that everyone inspect the radiator valves in their rooms to make sure they were fully open. My roommate and I thought we had fulfilled the order, but when an inspection team came round to verify, they found that our valve had stuck half-way open. More pressure on the handle would have broken it loose, but we hadn’t realized it wasn’t open all the way. So we both got a lot of gigs for that. I think I wound up with a total of 31, with fifty being the limit.

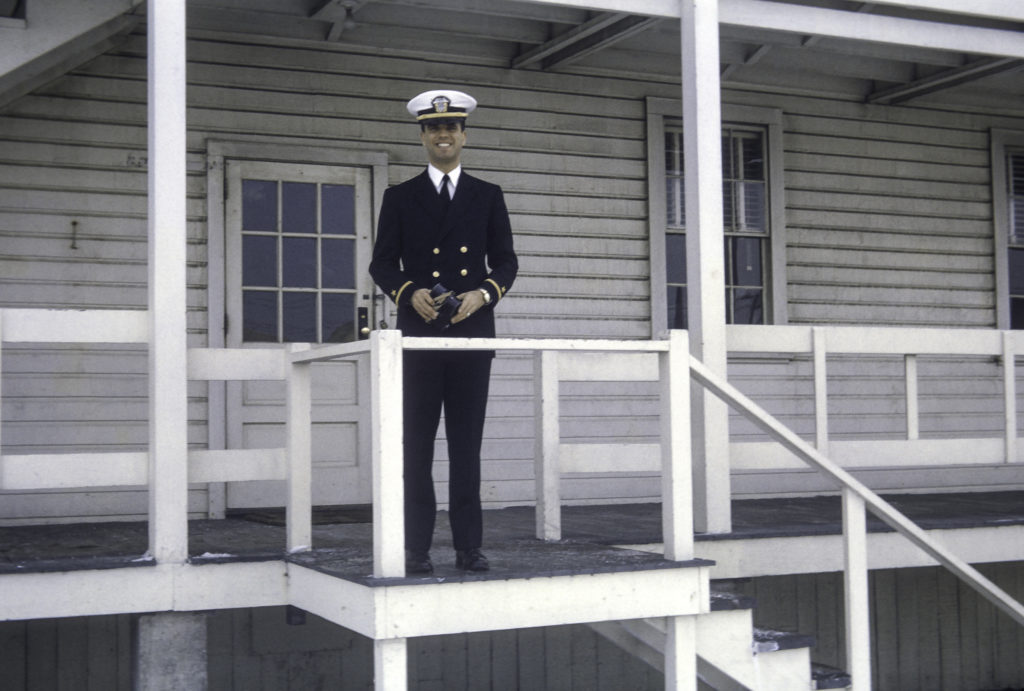

Nevertheless, I graduated, and by the time it was all over, on February 5, 1965, I had a 3.2 grade average, which wasn’t bad for OCS. The Company Commander, Lieutenant Johnson, upon seeing this, roared with laughter – “He worried so much, he worried himself right into a 3.2!”

Our duty assignments came in during our last week of OCS. I was assigned to U. S. Naval Facility (NAVFAC for short) Centerville Beach, Ferndale, California. I had no idea where it was – it turned out to be in Humboldt County, south of Eureka, the county’s largest city. One other person in my section was also assigned to a NAVFAC – Jim Davis, who was going to Nantucket. Prior to reporting to our duty stations, we had to go through two weeks of training at Naval Communications School in Newport, then another five weeks and Fleet Sonar School in Key West, Florida. During the two weeks in Newport, I bought a new car, a baby-blue Triumph Spitfire.

The Comm School training was mostly concerned with cryptography, and the lion’s share of that was in the operation of the ADONIS system. This was a lineal descendant of the World War II German Enigma system, which used rotors to encrypt messages into five-letter groups. Enigma, as is now well known, was cracked by a British team led by Alan Turing operating out of Bletchley, England. But whereas the Enigma system had used three rotors, ADONIS used eight, which was supposed to make the messages virtually impossible to decrypt, even with the aid of a computer, unless of course you had the key used to align the rotors to the appropriate positions.

Despite many warnings, during our instruction in the ADONIS system I managed to assemble the rotors incorrectly, inserting seven into the containing cylinder instead of eight, which resulted in jamming my ADONIS machine and bringing the class to a temporary halt while the instructor extricated the rotors. The instructor read me the riot act for that, and I felt like sliding through a crack in the floor. Even worse, one of my fellow students tried to offer suggestions about what he thought I was doing wrong, and I nearly jumped down his throat in reply. The problem wasn’t what he thought it was; rather it was that the class went too fast for me, and I was too slow to keep up the pace that the instructor was going at. I’m a slow person – I like to think it’s a case of still waters running deep, but it’s probably just plain being slow.

I think I used the ADONIS system all of once in my subsequent naval career. It was on San Nicolas Island, to decrypt a TOP SECRET message.

In addition to berating me for my screwups, the Comm School instructor tried to fortify us for Sonar School in Key West. He recounted that when he woke up after spending his first night in the BOQ, he found a large pile of sawdust on the floor. This had been produced by the termites who infested the rickety and rundown BOQ building, along with hordes of other insects, most of them obnoxious. To deal with them, he went out and caught a lizard, whom he quartered in his room. The lizard took care of the insects and he was able to recover his composure. Unfortunately, the Filipino stewards didn’t understand the role of the lizard and tried to get rid of it, and he had to issue blood-curdling threats to get them to desist.

After completed the Comm School course, I headed south for Key West in my new car. I acquired a passenger, a fellow student in the class named Al Bognacki, who needed a ride down to Key West and was willing to share gas costs. It was still February and bitterly cold. As soon as we left Newport, which was late at night, my new car started sputtering and threatened to quit. I pulled into a gas station and asked the attendant for help. He said that I had frozen water in my gas and that it was clogging up the carburetor. He came up with a can of some chemical which was supposed to thaw the ice in the gas and poured it into the gas tank. It worked splendidly, and we sped off into the night. Except for gas and food, we didn’t stop until we got to Key West.

We arrived in Key West during a driving rain. It was so humid that the windshield fogged up and I couldn’t see where I was going. The windshield wipers were no help – the inside of the windshield was fogged up too, and as I dragged a towel across the glass, the fog followed right behind my hand and covered the glass again. I had to stick my head out of the window in the rain to see where we were going. Somehow we made it to the base and checked into the BOQ without wrecking the car. Thus began my sojourn in the tropical paradise of Key West, Florida, a state I don’t care if I ever see again.