Our bus deposited us at the corner of Bajcsy-Szilinski Boulevard and Alkotm

We also passed the National Togetherness Monument (Nemzeti összetartozás emlékhelye in Hungarian), or National Unity Monument. Unveiled in 2020, it consists of a hundred meter long, four meter wide stone ramp descending underground, with an eternal flame burning at the end of the ramp. It is also known as the Trianon Monument because it laments the Treaty of Trianon, which ended World War I for Austria and Hungary, but also deprived the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary of two-thirds of its territory and imposed heavy reparations. The Treaty was dictated by the victorious Allies, and the Hungarians have resented it ever since. A major issue is that while the treaty rescued several non-Hungarian nationalities – Croats, Rumanians, Slovaks, etc. – from Hungarian domination, it also removed 3.3 million Hungarians, about a third of the Hungarian-speaking population, making them minorities in countries such as Rumania which benefited from the partition. The monument gives expression to irredentist sentiments by listing on its walls over 12,500 names of places in the pre-World-War I Kingdom of Hungary, many of which ended up in the surrounding countries in consequence of the Trianon Treaty.

We did not explore the monument, due to lack of time, but instead pressed on to Kossuth Square.

Kossuth Square is named for Lajos Kossuth, leader of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, which briefly succeeded but was ultimately suppressed by the Austrians with the crucial aid of an army dispatched by Tsar Nicholas I of Russia. After the suppression of the Revolution of 1848, Kossuth went into exile and died in Italy in 1894.

Kossuth Square is dominated by the House of Parliament (Országház), the seat of the National Assembly of Hungary (Országgyűlés), the largest building in Hungary. It is mostly symmetrical, with two main fa

On the north side of Kossuth Square stands the Kossuth Memorial. First inaugurated in 1927, the original memorial was replaced in 1950 by a different one more suited to the taste of the ruling Stalinist regime. Many years later, in 2014, the government of Hungary had the original monument recreated and installed in Kossuth Square. It depicts not only Kossuth himself but all the members of the first Hungarian parliamentary government during the 1848 revolution.

On the northern and eastern sides of Kossuth Square, facing the House of Parliament, stood several structures undergoing renovation. The most prominent of these was the former (and future) Palace of Justice, which was originally built in the 1890s to house the Hungarian Supreme Court (Magyar Királyi Kúria). After World War II, with the advent of the People’s Republic, the Kúria was abolished and its building was handed over first to the Labor Movement Institute of the Hungarian Workers’ Party, then to the Institute of Party History and the Hungarian National Gallery, and still later to the Museum of Ethnography. Now the Museum of Ethnography is in its new home in the Budapest City Park, and the Palace of Justice is being readied for the return of the revived Supreme Court, again named the Kúria.

Also under renovation are the Ministry of Agriculture building, to the south of the Palace of Justice, and the dilapidated office building on the north side of the square.

Just to the north of the House of Parliament stands a monument to Count István Tisza, who was the prime minister of Hungary during most of the First World War. Although he was a strong advocate of industrial development and a staunch foe of anti-Semitism, he was also adamantly opposed to democratic reforms. He was a firm adherent of the Dual Monarchy – the partnership with Austria – and a relentless supporter of Hungarian participation in the war effort. He was also a champion duelist, but this did not prevent his assassination by leftist revolutionaries in 1918.

Next to the Tisza Monument is the Visitors’ Center, where we took a short break and then resumed our hike around the square, heading west toward the Danube riverbank. There we enjoyed some great views of Buda, especially Buda Palace and Castle Hill, as well as of the river itself with its myriad watercraft.

I was also able to get some nice shots of the west fa

J

At Parliament Point stairs are provided for climbing back up to Kossuth Square, which at this point is above street level. But before making the climb, we had one more stop to make: the Shoes on the Danube.

By October, 1944, it had become abundantly clear to Miklós Horthy, Regent of Hungary, that the Hungarian alliance with Nazi Germany was no longer a good idea, and he attempted to conclude an armistice with the Soviets, whose armies were crashing into Hungary. To forestall this Adolf Hitler sent his favorite commando, Otto Skorzeny – the man who rescued Mussolini from jail in 1943 – to give Horthy the boot. Skorzeny engineered a coup in which Ferenc Sz

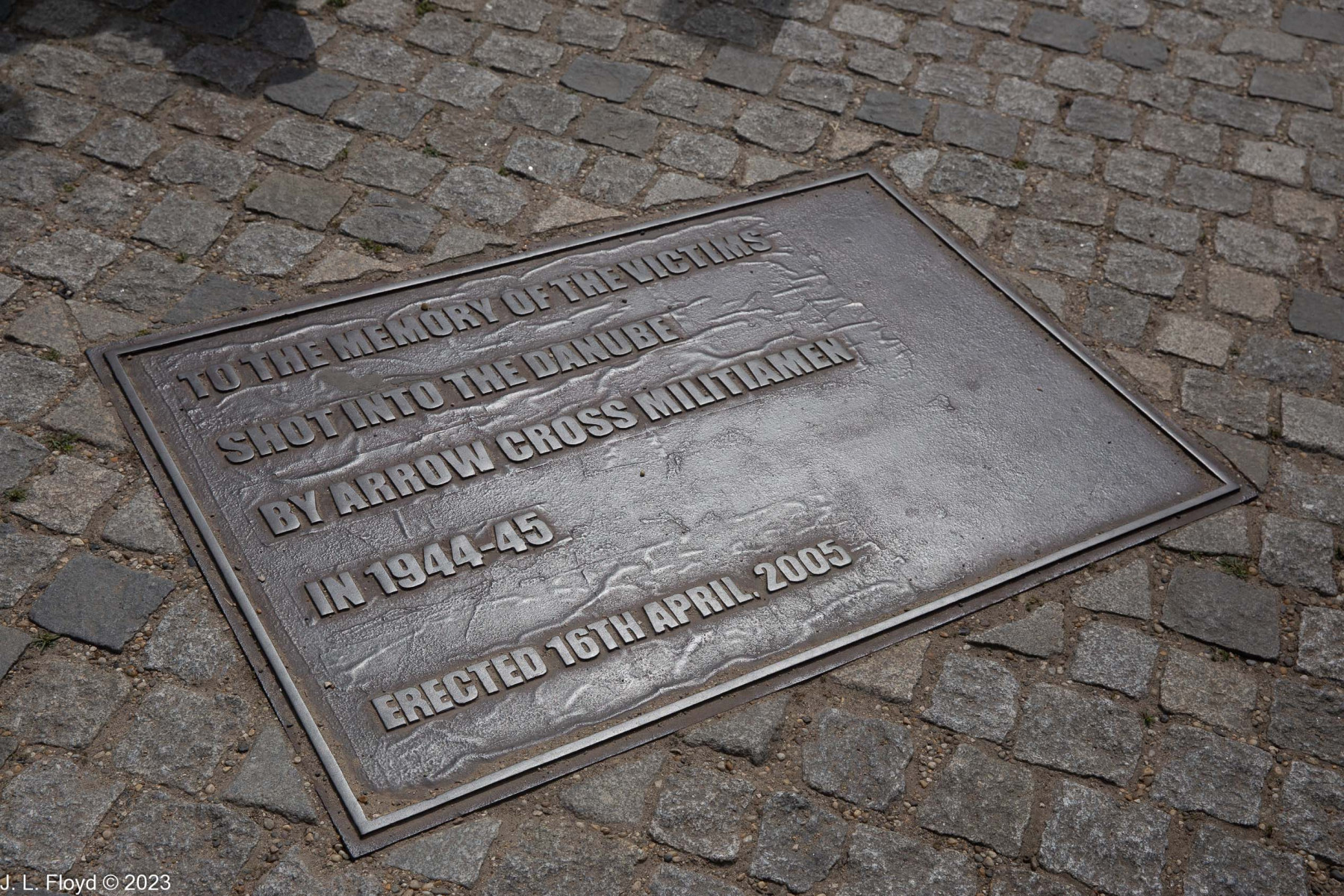

Many years later, a film director named Can Togay conceived the idea of creating a monument to the victims of the riverside massacres. He joined forces with a sculptor named Gyula Pauer, who fashioned 60 pairs of shoes out of iron, replicating types and styles of footwear worn in World War II. The shoes are true to life in size and detail, and a full range of shoes are represented – men’s, women’s and children’s. The shoes were installed on the promenade near Parliament Point on April 16, 2005. Nearby are commemorative plaques in Hungarian, English and Hebrew. The one in English reads “To the memory of the victims shot into the Danube by Arrow Cross militiamen in 1944–45. Erected 16 April 2005.” The Shoes monument is one of the most heavily visited sites in Budapest, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors per year.

Leaving the Shoes monument, we climbed the steps at Parliament Point to complete our tour of Kossuth Square. On the south side of the square we found several more monuments commemorating important events and personages in Hungarian history.

Just south of the House of Parliament there is an equestrian monument of Count Gyula Andrassy. Andrássy was a prominent figure in the revolutionary movement of 1848 and had been sentenced to death by the Hapsburg government, which he avoided by emigrating. But in 1858 he returned to Hungary, somehow managed to reinstate himself in the good graces of the Imperial authorities, and became active again in politics as a reformer. Following the Compromise of 1867, which marked the formation of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, he was appointed the first prime minister of Hungary. Later he served as Foreign Minister of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Not far away, in front of the south wing of Parliament, stands a monument of a very different sort. It is a gray stone block with a flat top, completely bare except for the inscription on its face: “IN MEMORIAM 1956. oct

In a large green space in the southeast corner of Kossuth Square I spotted another equestrian statue with the name Rákóczi on the plinth. I had heard the name before but knew little about the person to whom it belonged, and I wanted to get some good shots of the monument so I could look him up and find out more. It turns out that Ferenc Rákóczi was a Hungarian nobleman, indeed a scion of the the richest family in the kingdom, who led an unsuccessful revolt against the Habsburgs in the early 18th century.

After retaking Hungary from the Turks at the end of the 17th century, the Austrians treated it as a conquered province with which they could do as they pleased. What pleased them most was to confiscate the estates of Hungarian nobles, especially Protestants, of whom there was a sizeable number in Hungary and whose loyalty was suspect, and award the land to outsiders, especially Catholic Austrian Germans. In 1703, with the Habsburgs fully engaged in the great War of the Spanish Succession, a desperate struggle with King Louis XIV of France, the disgruntled Hungarians thought they had their chance and rose in revolt. Rákóczi assumed leadership of the rebellion and for a time it appeared that the anti-Hapsburg forces would succeed, since they held most of Hungary east of the Danube; but eventually the French war wound down, and the Habsburgs were free to turn their full force against the rebels. Rákóczi fled to Poland and attempted to obtain help there, but in his absence the commander of the rebel army signed a peace treaty with the Habsburgs, who agreed to rule according to the constitution and laws of Hungary and to grant an amnesty to the rebels in return for their submission to the Crown. Rákóczi himself did not accept this settlement, and went into exile, ultimately defecting to the Ottoman Turks; but today he is regarded as a national hero in Hungary.

If it seems that I’ve included an excessive number of photos of the Rákóczi Monument, it’s because of all the trouble taking those photos caused me, which was almost as much as Rákóczi had caused for the Habsburgs. I was so anxious to obtain a good photo of his monument that I failed to keep track of the tour group. When I finished taking my pictures, I looked around and saw nobody I knew. I could hear Erika, the tour guide, on my Vox-box but I couldn’t see her, even with the flag she held to ensure she was visible from a distance, and I had no idea which direction she had taken. Soon I couldn’t hear her either. I looked for Sandie, who had been at the tail end of the group in the company of Nico, the Gate1 director who was making sure she didn’t get left behind, but they had vanished too.

For some reason I had the notion that the guide intended to completely circle the Parliament building and return to the Visitors’ Center before heading back to the bus. So I headed back to the Visitors’ Center, which turned out to be exactly the wrong direction. I soon realized that I was lost in Budapest, hot, tired and hungry, with no idea how to reconnect with the tour guide, and no idea how to get back to the Monarch Queen.

For the exciting conclusion to this cliffhanger, you’ll have to read the next post.