The Dohány Street Synagogue is affiliated with the Neolog or Congressional wing of Hungarian Jewry, a liberal and modernist denomination largely associated with middle and upper-class assimilated Jews, in sharp contrast to the conservative and traditionalist Orthodox Jewish community. The latter have their own places of worship, one of which is the Kazinczy Street Synagogue, which was our second stop in the Jewish Quarter. To get there we threaded our way through narrow, crowded streets, passing a number of interesting shops and tempting restaurants which I would have loved to patronize if there had been an opportunity.

The Kazinczy Street Orthodox Grand Synagogue was built in 1913, just before the First World War, in a style which is the last thing I would have expected from a conservative and traditionalist denomination: Art Nouveau. In fact it is considered a masterpiece of Art Nouveau architecture. The narrow street and the limitations of my equipment (not to mention the skills of the photographer) prevented me from doing visual justice to the synagogue, but one can see more adequate photos online, for example here. In the post-World War II period, under the kindly auspices of the Communist regime, the Orthodox Grand Synagogue deteriorated to the point of unusability, and a smaller house of worship, the Sasz-Chevra Orthodox Synagogue, was built next to it (after the collapse of Communism the main synagogue was restored and can be visited today). I initially mistook the unpretentious doorway providing entry to the smaller synagogue, which also leads to the Hanna glatt kosher restaurant, for the main entrance to the Grand Synagogue.

From Kazinczy Street we ambled on to the Carl Lutz Memorial, at the corner of Dob and Rumbach Streets. Carl Lutz was a Swiss diplomat who is credited with saving 62,000 Hungarian Jews from the Nazis during World War II.

Interestingly, Carl Lutz as a young man had emigrated to the United States. He lived there for two decades and worked his way through college, graduating from George Washington University in Washington, D.C., in 1924. By that time he had started working in the Swiss Legation there, and continued to pursue his diplomatic career in other American cities, remaining in the USA until 1934. In 1935 the Swiss diplomatic service sent him as a vice-consul to Jaffa in Palestine, where he apparently developed strong Jewish sympathies after watching a Jewish worker being lynched by an Arab mob. In 1942 he was appointed Swiss vice-consul in Budapest, and soon began helping Hungarian Jews emigrate to Palestine. He did so by issuing safe-conduct documents to Jewish families and by establishing safe houses, such as the famous “Glass House”, where Jews could live under official Swiss protection. His activities became so provocative that the German plenipotentiary in Hungary actually contemplated having him assassinated, but failed to obtain permission from his superiors. The Swiss government’s reward for his efforts was to reprimand him for exceeding his authority, though this was later reversed. He died in Switzerland in 1975.

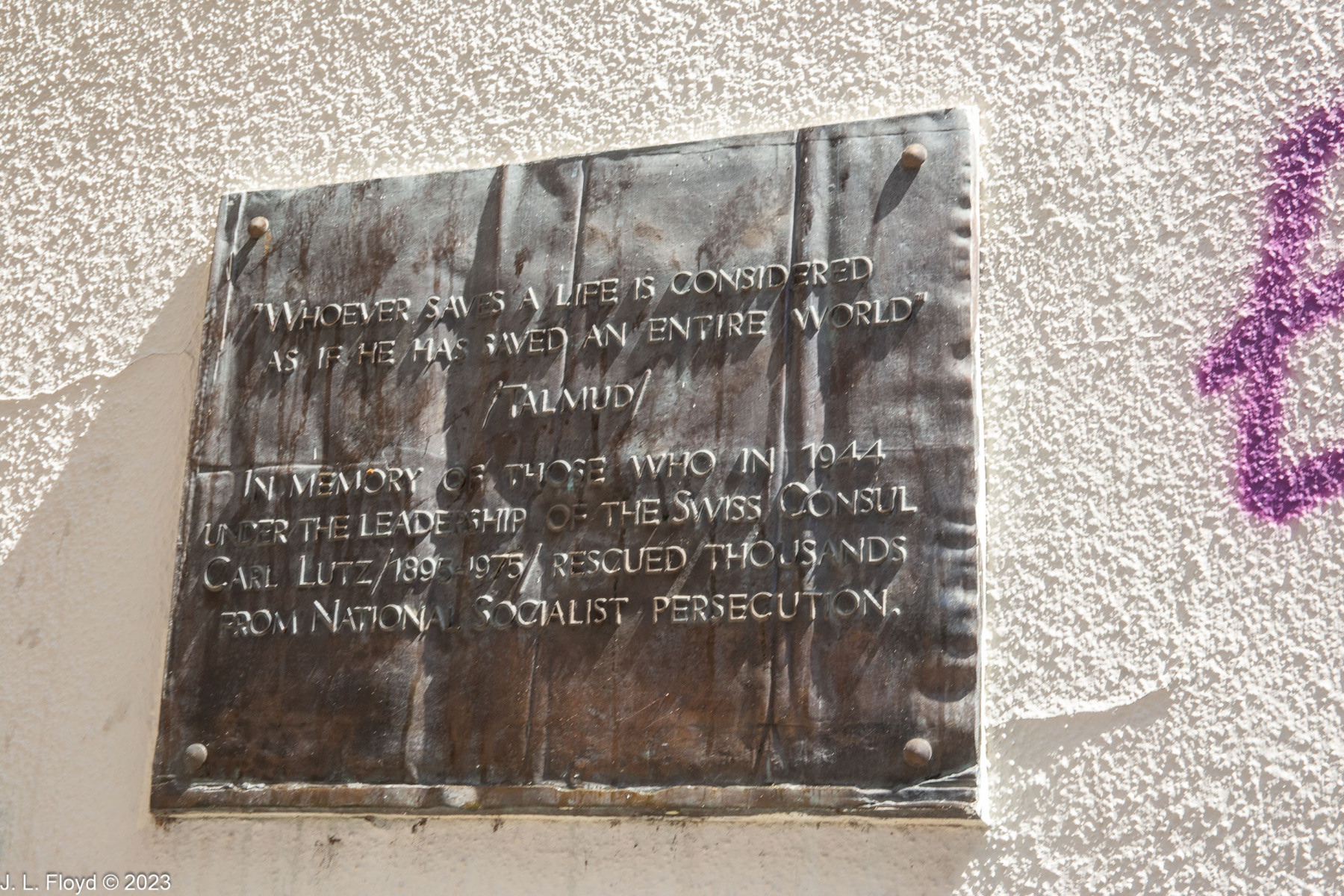

The Carl Lutz Memorial on Dob Street is a most unusual construction. Its most striking component is a statue of Lutz in the form of a golden angel standing sideways on the side of a building. From his height, Lutz throws a very long cape to serve as a ramp for an wounded Holocaust victim lying on the ground. extending an arm up to plead for help. Also on the wall is a plaque featuring a quotation from the Talmud, “Whoever saves a life is considered to have saved an entire world.” Beneath the golden statue on the wall have been scrawled a plethora of graffiti, which some people feel has ruined the atmosphere, but it didn’t bother me. The graffiti were unintelligible to me, and I could not tell whether they consisted of the ravings of anti-Jewish hatemongers displaying their idiocy for all the world to see, or else they have nothing to do with the memorial at all, in which case they are merely artwork. In any case, the memorial is set in a shady garden which provides a semblance of peace. On the street corner, at the opposite end of the garden from the memorial itself, we noticed three mounds which consisted of the same kind of brickwork as that supporting the victim statue, but which had nothing near them to indicate what they represented. I don’t recall whether the guide said anything about them and I haven’t been able to find out anything more, so if anyone reading this can help I would be much obliged.

Turning the corner of Dob and Rumbach Streets, I found a graffiti-bedecked parking lot which turned out to be the base of an outfit calling itself Hot Rod Budapest, which offers tours of the city in fake “Deuces” – cut-down, souped-up 1932 American Ford open roadsters. Although these are obviously cheap imitations of the real thing, we would have tried them if we had a chance; we did something similar a few days later, in Prague, and enjoyed it greatly.

Continuing down Rumbach Street, we came across the Frogbite Tattoo Parlor. I don’t favor tattoos myself but I loved the name of the place. I had an old friend from FileNet days (mid-80s), Dennis Griesser, who was a ranarophile, otherwise known as a frog freak. I would have sent him a picture of the logo, but he passed away earlier this year. This page is dedicated to him in memoriam.

Also on Rumbach Street we encountered a number of other enticing establishments, such as the gaily decorated Bluebird Cafe, where I shot a picture of the entrance with an attractive young member of our tour group in front.

The Rumbach Street Synagogue is an octagonal structure built in 1872 in Moorish Revival style, like the Dohany Street Synagogue. In fact it was intended for the Neolog branch of Hungarian Jewry, but in the 1870s the schism between the Orthodox traditionalists and the Neolog modernizers evolved into a three-way split, with another conservative branch following its own path, to become known as the “Status Quo” faction; and the Rumbach Street Synagogue came under their aegis. Like the other two synagogues we viewed, the Rumbach deteriorated badly in the late 20th century, and was eventually restored to its pristine grandeur; today all three rank among the top architectural wonders of Budapest.

From Rumbach Street we headed back down Dob Street toward Károly Boulevard, a wide main thoroughfare which converges with Dohány Street near the Great Synagogue, where our bus awaited. On the way I was able to capture a few more subjects of interest with my camera, including a couple that probably won’t show up in any guidebooks.

For example, I noticed that in the crowded Jewish Quarter some attempts had been made to maximize the use of real estate by building archways spanning the space between buildings over an intervening street. An example is shown below.

Károly Boulevard and Dohány Street mark the border of the Jewish ghetto of World War II, and the “Gentile” side of the street is lined with upscale apartment buildings, pricey boutiques and posh hotels. Nevertheless, I found a specimen of the ubiquitous Budapest graffiti even here, and in a rather inaccessible yet highly visible place.