On a foggy March morning we explored the mist-enshrouded ruins of the ancient city of Hierapolis. Hierapolis means “Holy City” in Greek; it was supposedly called thus because of the large number of temples found there. It is located in what was in ancient times the kingdom of Phrygia, famous for such legendary characters as Midas, whose touch turned everything to gold, and Gordias, who tied the Gordian knot.

Hierapolis came to prominence as a health resort during the second century BCE. People came to retire or seek healing there because of the supposed medicinal properties of its thermal baths. Many of them, being ill, died there also; Hierapolis consequently became the site of a large necropolis, situated at the north end of the city, and that was where we began our visit.

It turned out that Lara Croft, Tomb Raider, had beaten us here, so the tombs were empty and there was nothing left to plunder.

Grass grows on some of the tombs, and sheep graze there. I thought it was decent of the authorities to let the shepherds pasture their sheep in the ruins.

Of course, sheep need a shepherd, and a shepherd needs a dog. We enjoyed hobnobbing with both of them, and Attila translated for us.

Some of the other local residents showed up too, and kept Sandie and Cherie company for a while, along with their plump and fuzzy sheep.

One of the shepherds helped Cherie zip up her jacket to keep warm. It was chilly, even after the fog lifted.

The Basilica Bath is at the north of Hierapolis, between the necropolis and the Gate of Domitian. It was built during the 2nd century CE and was converted into a basilica church during the reign of Justinian, in the 6th century CE. There was another, better preserved bath complex at the south end of the city; it houses the Museum of Hierapolis.

Somewhere along the main drag, we came across this edifice, with a large stone block precariously suspended between two others. I wondered whether this was by chance or design.

I also wondered whether the stone arch in the next picture was the legacy of an existing structure that had collapsed, the result of a partial restoration, or the product of an archaeological prank. We found no answer to this question then or later. I opted for the third choice. What do you think?

The next identifiable landmark was a monumental gate built by the Roman proconsul Julius Frontinus in 84-86 CE. It consisted of three triumphal arches flanked by two circular towers (see next photo).

The Gate built by Frontinus is also known as the Gate of Domitian, since it was built during his reign, which lasted from 81 to 96 CE. Domitian was the third and final emperor of the Flavian dynasty, the son of Vespasian, a general who led the Roman suppression of the revolt of Judea (66-70 CE) before seizing the throne, and the younger brother of Titus, who completed the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE. Domitian himself played little part in those events, and had no significant accomplishments before coming to the throne on the untimely death of his older brother; he was apparently not a charismatic leader or a very attractive person, and hasn’t fared well at the hands of ancient historians such as Tacitus and Suetonius, who considered him a cruel and paranoid tyrant. He was assassinated in a court conspiracy in 96. Modern revisionists have tended to treat him more favorably, some crediting him as a “ruthless but efficient” autocrat who sponsored reforms which laid the foundation of the peace and prosperity enjoyed by the Roman Empire during the second century CE.

South of the Domitian Gate lay the confusingly named Northern or Byzantine gate, which was built not during the Byzantine period but during the reign of Theodosius (late 4th century CE) as part of a system of fortifications. Like the Domitian Gate, the Byzantine gate was also a monumental entrance, with two large square guard towers at either side. The 4th century was a more troubled time than the 2nd, and one may guess that the city was undergoing contraction and retrenchment from the fact that the Byzantine gate was constructed using stone plundered from the agora, which lay just to the east.

Now and then we encountered signs warning that picnicking in Hierapolis was disallowed. It was fortunate that the Turkish words were accompanied by an English translation; otherwise we might have thought that they said something like “Official Picnic Area.” Turkish, being a non-Indo-European language, is rather opaque to me.

South of the Byzantine gate we encountered the Temple of Apollo, originally built during the Hellenistic period (late first millenium BCE) but reconstructed during the 3rd century CE. Inside the sacred court (peribolos) surrounding the temple, a shrine called the Nymphaeum was built in the 2nd century CE. This was a monumental fountain which distributed water to the houses of the city via a network of pipes.

To be quite honest, I wasn’t able to distinguish between the ruins of the Temple of Apollo and the Nymphaeum – the signs didn’t quite make it clear precisely where one ended and the other began, or which stones belonged to which structure. I’m guessing that the Nymphaeum included both the rectangular structure facing the main street and the adjoining arched building behind it, and that the latter held the fountains. The signage was more concerned with preventing picnics than providing information about the ruins.

In any case, the Temple of Apollo was deliberately built on an active earthquake fault, as was the temple of the same god at Delphi. In both locations, noxious gases emanated from the chasm. In Delphi, the vapors were inhaled by the Pythia, the priestess of Apollo, who went into a trance under their influence and uttered prophesies. In Hierapolis, however, Apollo had to share the site with Pluto, the god of the underworld, as well as the mother-goddess Cybele, who was the national deity of Phrygia. She was known as Magna Mater in Rome. The priests of Cybele, the Galli, were required to be eunuchs, so they had to castrate themselves to enter the priesthood; this was thought to confer on them powers of prophecy.

Next to the temple of Apollo was located the Ploutonion, the shrine to Pluto, a sinister-looking structure leading to a small cave which in ancient times emitted gas from the earthquake fault. According to Wikipedia, the gas involved was carbon dioxide, but I suspect that something more lethal was involved, most likely sulfur dioxide, because it was said to cover a 2,000 square meter area in front of the entrance and kill any living creature that entered the area. The priests of Cybele, who managed the site, sold birds and small animals to pilgrims so that they could thrown them into the fog to demonstrate how deadly it was. Then they would go into the shrine, and, holding their breath, seek out the pockets of oxygen which they knew the poisonous gas would leave because it was heavier than air, subsequently emerging unharmed as “proof” that they were under divine protection. Convinced of the priests’ divinely bestowed powers, the pilgrims would then pay exorbitant fees for Pluto’s prophesies, providing a lucrative source of income for the temple.

In the 4th century, as Christianity became dominant throughout the Roman Empire, its adherents, as part of the effort to eliminate the competition, desecrated the Temple of Apollo and walled up the Ploutonium. Later earthquakes completed the destruction.

The Amphitheater of Hierapolis was built during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 CE) and remodeled in the early 3rd century. It was considered one of the largest and finest in the ancient world and seated 15,000 people. It was wrecked by an earthquake in 614 CE.

At the time of our visit, the theater was undergoing restoration. You could still walk up the hill to see it; some did, and shot some magnificent pictures, but Sandie and I did not, which I regret.

Our visit to Hierapolis fell on a Monday, and the Museum is closed on Mondays, so we didn’t get to see it. This was unfortunate, because the Museum was housed in the old Roman baths, worth seeing in themselves; plus it contained numerous historical artifacts, dating all the way back to the Bronze Age, unearthed by modern excavations.

The ultimate source of Hierapolis’ prosperity, of course, was the spa, which consisted of a number of pools. Shown below is the Antique Pool, which is filled with the ruins of a marble portico which was destroyed by the great earthquake of 614 CE.

In the mid-20th century, hotels were built over the hot springs, causing considerable damage to the travertine terraces. When Hierapolis was declared a World Heritage Site in 1988, the hotels were torn down and replaced with artificial pools, like the one shown below, which is known as Cleopatra’s Pool. New hotels, such as the one we stayed in, were built in more ecologically favorable locations, and the spa continues to be a tourist attraction.

The ancient city of Hierapolis is also the site of the modern town of Pamukkale, which means “cotton castle” in Turkish. The name refers to the fluffy-looking terraces composed of calcium carbonate deposited by the water from the thermal springs.

When water from the hot springs, supersaturated with calcium carbonate, reaches the the surface, carbon dioxide degasses from it, and the mineral precipitates out as a soft gel. Eventually the gel hardens into travertine.

At the foot of the cotton castle lies the modern town of Pamukkale, where the residents spend their free time flying balloons over the cliffs.

The water from the hot springs forms pools at the top of the cliffs, where you can take off your shoes and go wading. Most of us did just that. The seemingly placid waters posed hazards, however, as we shall see.

There was a path from the town up the hill to the wading pools, and some travelers came up that way.

Elouise and Chuck Mattox found the water to their liking, as did Rick Gering.

As noted above, the calcium carbonate suspended in the spring water initially precipitates out as a soft and very slippery gel. Insufficiently careful waders – and you had to be very careful to avoid this – soon discovered the hazard that lay in wait here.

Sandie wisely declined to risk taking a spill and getting soaked in the wading pool, and posed demurely in front of the white cliffs.

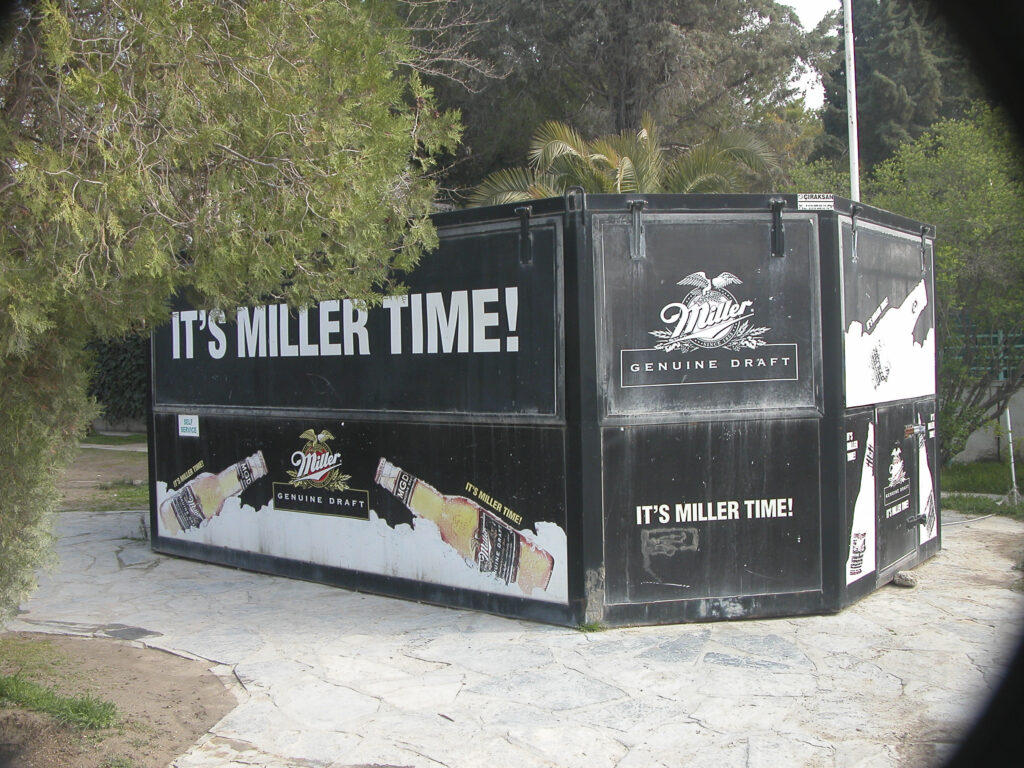

Turkey, of course, is an Islamic country, and Islam forbids the consumption of alcohol, so it was a bit of a surprise to me to encounter a billboard prominently displaying a beer ad next to the spa pools. But, as our guide Attila explained, the Turks believe that such strictures can be relaxed, provided it’s done with an appropriate dose of moderation. I should also note that the Turkish national spirit is raki, which is distilled from grapes, with a touch of anise. It is similar to the Greek beverage ouzo, but is said to be much stronger. Several people in our tourist group developed a taste for raki.