On the morning of April 1, 2006, our tour group visited what I regard as one of the greatest monuments in the world, the former basilica, later mosque, later again museum, and now again (as of 2020) a mosque, Hagia Sophia, or Aya Sophia as it is known in Turkish.

Hagia Sophia was built in the reign of the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I and completed in 537 CE. At the time it was the world’s largest cathedral and remained so until the completion of the Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville, Spain, in 1520.

The name Hagia Sophia does not pertain to any particular saint but rather means “Holy Wisdom,” referring to Jesus Christ.

Over the centuries Hagia Sophia has undergone many changes, as a result of both natural disasters and human events. Among the first of the former was the cracking of the main dome and collapse of the eastern semi-dome in 558, destroying the altar area. The main dome had to be completely rebuilt, but the result has survived, with some reinforcement and repair, down to the present day. I’ll mention some of the other circumstances in the course of this post.

The day before, our guide, Attila Mahur, had warned us that avian flu had been going around in Turkey, and he recommended that we wear masks the following day. Now I had read, before embarking on the trip, that avian flu was circulating in Turkey. Not only that, but I was a bit apprehensive about the long flight from Chicago to Istanbul and back again, because every time I had flown commercial aviation over the previous few years I had contracted a respiratory illness, so I had brought along a box of surgical masks and had even worn one on the flights to Turkey. I took Attila’s warning seriously and wore one of the masks on our last day in Istanbul, when we boarded the bus to head for Hagia Sofia.

I had no idea at the time that April Fool’s Day was observed in Turkey. Once we arrived at Hagia Sophia, Attila removed his mask and cheerfully confessed to his mischief. Either because I was the only person to bring masks on the trip, or because I was the only one dumb enough to fall for the joke, I was almost the only person who had a mask on at the time. Actually a couple of others had worn masks, but I think they just did it to humor Attila and weren’t actually fooled.

The Hagia Sophia that we saw is at least the third church to be built on the same site. The first was the Magna Ecclesia of Constantius II, son of Constantine the Great, built around 360 CE. It burned down during a riot in 404 CE. The second was commissioned by Emperor Theodosius II and completed by 415; it burned down during the Nika riots of 532. Emperor Justinian then began construction of a new church, which was completed in 537. During the 1930s, excavations conducted by a German archaeologist unearthed fragments of the old Theodosian church; they are now displayed in an area outside the existing Hagia Sophia.

The Corinthian-style column capital pictured below is one of the few surviving remnants of the Theodosian church.

Another remnant of the Theodosian church is the frieze with lambs pictured below, representing the twelve apostles of Christ.

The Imperial Gate, or Emperor’s Door, is the largest entrance to Hagia Sophia at 21 meters, or 23 feet, in height. Legend says that it was made of wood from Noah’s Ark or the Hebrew Ark of the Covenant. It is made of oak, with a bronze frame. Entry was restricted to the Emperor and his entourage. The mosaic in the tympanum above the door dates from the late 9th or early 10th century and depicts Christ seated on his throne, with the emperor bowing down to him. The circular medallions on either side feature busts of Christ’s mother Mary and the Angel Gabriel.

A narthex is defined as “A western vestibule leading to the nave in some (especially Orthodox) Christian churches.” Hagia Sofia has a double narthex, with both an outer (exo-) and an inner (esonarthex). A ramp from the northern part of the outer narthex leads up to the upper gallery.

The exo-narthex is huge and has a number of doors, each one with a distinctive design.

We caught a glimpse of the nave (central part of the church, on the ground floor) before proceeding to the upper level. It was evident from the scaffolding that extensive restoration work was going on.

Ascending to the second floor, we found ourselves in the upper gallery, which encloses the nave of the church on three sides; the fourth side is occupied by the apse. (For those not familiar with church architecture, the apse is a large semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault; the nave is the central part of a church building, intended to accommodate most of the congregation.)

After the Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque, and over the centuries a number of Muslim decorations and symbols were added. Most prominent and striking are the huge green medallions hanging on the walls of the nave, added in conjunction with restoration work undertaken performed in 1847-49. They are inscribed with the names of Allah, Muhammad, the first four caliphs, and the grandchildren of Muhammad. In my view they clash with the rest of the decor.

The central section of the upper gallery, above the Imperial Gate, contains the Empress’ Loge, and the north side the matroneum, or women’s gallery, from which the empress and the ladies of the court could watch church services.

I admired the way that the green marble columns were joined to and integrated with the gallery arches throughout the building. This close-up shot of a double-column capital is from the Empress’ Loge.

At each corner of the square formed by the upper galleries, there is an exedra – a semicircular columned recess which relieves the starkness of sharp corners and provides nooks for conversation.

From the south gallery, we were able to get a good view of the ground floor entry and the Empress’ Loge on the west side.

Attila began our exploration of the upper gallery by discoursing on its architecture and decor to the assembled tour group. The beautiful green marble used for the gallery columns, as well as elsewhere throughout the cathedral, came from Thessaly in northern Greece.

The immense main dome of Hagia Sophia has 40 windows, which both reduce the weight of the dome, making it easier to support, and in combination with the windows in the walls, flood the interior of the nave with light, creating an effect of the dome hovering in the air.

We developed a fascination with the details of the column capitals, which came in a number of somewhat different though similar styles, each with its own design, but all equally intricate and finely crafted.

Columns and other marble elements were imported from throughout the Mediterranean world for the construction of Hagia Sophia.

Even though the columns were made specifically for Hagia Sophia, they vary in size and style.

The intricately carved column capitals in the upper galleries are called “basket capitals” and are carved with the monograms of Emperor Justinian, his wife Theodora, and their titles.

In the Southern Gallery there is a chamber that was used in Byzantine times for conclaves of church officials, such as patriarchal synods. It is entered through the famous Marble Door, which features panels with plant, fruit and fish motifs. Supposedly one side of the door is supposed to represent heaven and the other side hell. I wasn’t aware of that at the time, and I didn’t study it closely, so I have no idea which is which; but I suspect that hell could be found on both sides of the door.

In 1204 the Roman Catholic Pope Innocent III initiated a new Crusade (the Fourth, officially) with the aim of retaking Jerusalem, which had been wrested from Christian control in 1187 by Saladin. Over the Pope’s objections, the Venetians, under the leadership of their Doge, Enrico Dandolo, diverted the Crusaders to attack Constantinople instead. This led to one of the most infamous episodes in medieval European history. The Crusaders, taking advantage of a succession crisis in the Byzantine Empire, first gained control of the city, then sacked it, massacred much of the population, desecrated the churches, and looted the treasures of the city. Hagia Sophia of course did not escape their ravages, and the church was stripped of everything that could be carried off, as well as being vandalized. Fortunately, the great mosaics were up high, hard to reach, and not easy to remove and carry off, so many of them survived.

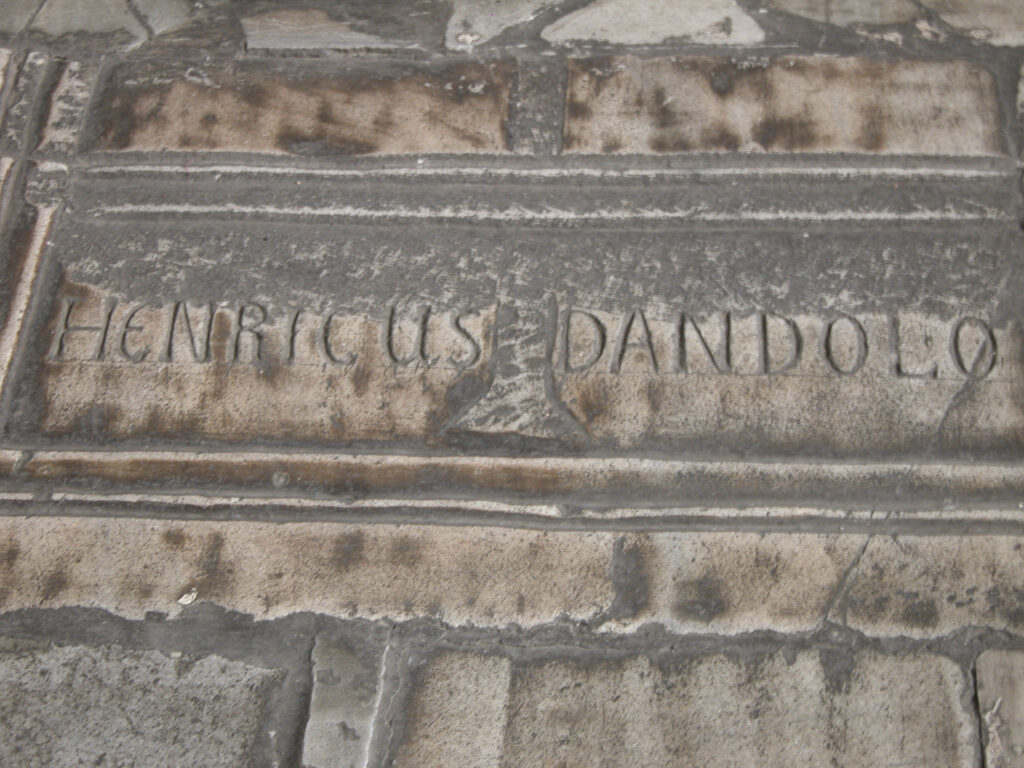

Enrico Dandolo, a very long-lived man, was already 97 (and blind) at the time of the sack; he died soon after, in 1205, and was buried in Hagia Sophia. Following their conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottomans destroyed his tomb, so that the plaque here is only a cenotaph, installed in the 19th century by an Italian restoration team.

Neither Sandie’s camera nor mine had flash equipment adequate to cope with the low lighting inside Hagia Sophia. Sandie’s Canon, if I recall correctly, had no flash at all and was thus utterly dependent on ambient light. My Nikon had a rather puny flash and was unable to illuminate very dark corners effectively. As a result, many of our photos taken inside the cathedral turned out quite blurry and indistinct. But in a few cases we were able make lemons into lemonade, as the saying goes, and turn our cameras’ shortcomings to our advantage. The next picture, taken by Sandie in the upper gallery, is a case in point. I doubt that she had any idea that she would create this amazing light show, but that’s how it turned out.

The southern part of the upper gallery, the Emperor’s turf, contains some of the most famous and best-preserved mosaics. Although mosaics were part of the original ornamentation of the church, most were destroyed during the period of the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy, which broke out in 726 CE and continued, on and off, until 842. The controversy arose from a conviction which took hold among some circles of the Eastern Orthodox church that too much veneration, verging on idolatry, was being accorded to religious images, in violation of scriptural prohibitions on the worship of graven images. Some of the emperors, adhering to the iconoclast position, attempted to enforce a ban on religious images, removing them from churches and other locations by force, against fierce resistance and violent protests among many sectors of the population. The Roman Papacy refused to support the iconoclastic movement, contributing to a growing estrangement between the Eastern and Western branches of Christianity. In the end the opponents of iconoclasm won out, and the creation and placement of icons in Byzantine churches resumed. Thus, most of the surviving mosaics in Hagia Sophia date from the later 9th century onwards.

Where the colorful arched ceilings with their elaborate abstract figures met the marble walls of the gallery, they were bordered by alabaster reliefs, as seen in this detail photo.

The Empress Zoe mosaic, on the eastern wall of the southern gallery, dates from the mid-11th century. It features Christ Pantocrator (“Almighty” in Greek), a specific type of depiction of Christ seated on a throne holding a Bible in his left hand and giving a blessing with his right. Here he is flanked by Emperor Constantine IX on his right and Empress Zoe on his left. The Emperor is holding a purse, symbolizing donations made to the church, while the Empress is presenting a scroll listing all her good works.

The Comnenus mosaic is also on the eastern wall of the southern gallery. It features the Virgin Mary seated, with the Christ child on her lap, holding a scroll in his left hand and giving a blessing with his right. On their right is Emperor John II Comnenus, holding a purse, and on their left is Empress Irene, bearing a scroll. Empress Irene was a daughter of King Ladislas I of Hungary.

The Deësis mosaic, also on the eastern wall of the southern gallery, is from a later time than the Empress Zoe and Comnenus mosaics. The Latin Fourth Crusaders, after sacking Constantinople in 1204, set up their own regime, the Latin Empire, as a replacement for the Byzantine Empire. Baldwin, count of Flanders, was crowned Emperor in Hagia Sophia. But the Latin Empire lasted only a few years. Byzantine aristocratic refugees escaping the sack of Consantinople regrouped and established their own successor states, one of which, the so-called Empire of Nicaea, eventually retook Constantinople in 1261 and re-established the Byzantine Empire. The Deësis mosaic was commissioned to commemorate the return of Hagia Sophia to the Orthodox Church. It features Christ Pantocrator in the center, along with the Virgin Mary on his right and John the Baptist on his left. Deësis means entreaty, and the two are interceding for humanity on Judgment Day. Unfortunately, the bottom part of the mosaic has suffered greatly from the ravages of time.

Despite the 1261 restoration, the Byzantine Empire never recovered its former extent or strength; it was beset on all sides by increasingly voracious enemies, both Christian and Muslim, and after precariously clinging to life another two centuries, finally fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

From the upper gallery we descended through a dark passageway back to the ground floor.

Upon reaching the ground floor again, we immediately encountered the famous “wishing column”, alternately known as the “weeping column”, or the “perspiring column,” or the “crying column”. Legend has it that the spirit of a saint named Gregory the Miracle-worker, a third-century bishop of Neocaesarea, appeared near the column in 1200. The legend further states that after the apparition of 1200, the column began to exude moisture. Touching the moisture, which Christians tended to view as the tears of the Virgin Mary, and Muslims saw as the tears of the Sultan, was supposed to cure various illnesses. Over time, so many people touched the column that they wore a hole in it. Then bronze plates were installed on the column to protect it, but people continued to touch it and ended up wearing a new hole in the bronze plate over the old hole. Now the legend says that if you stick your thumb into the hole, rotate it 360 degrees and make a wish, your wish will come true.

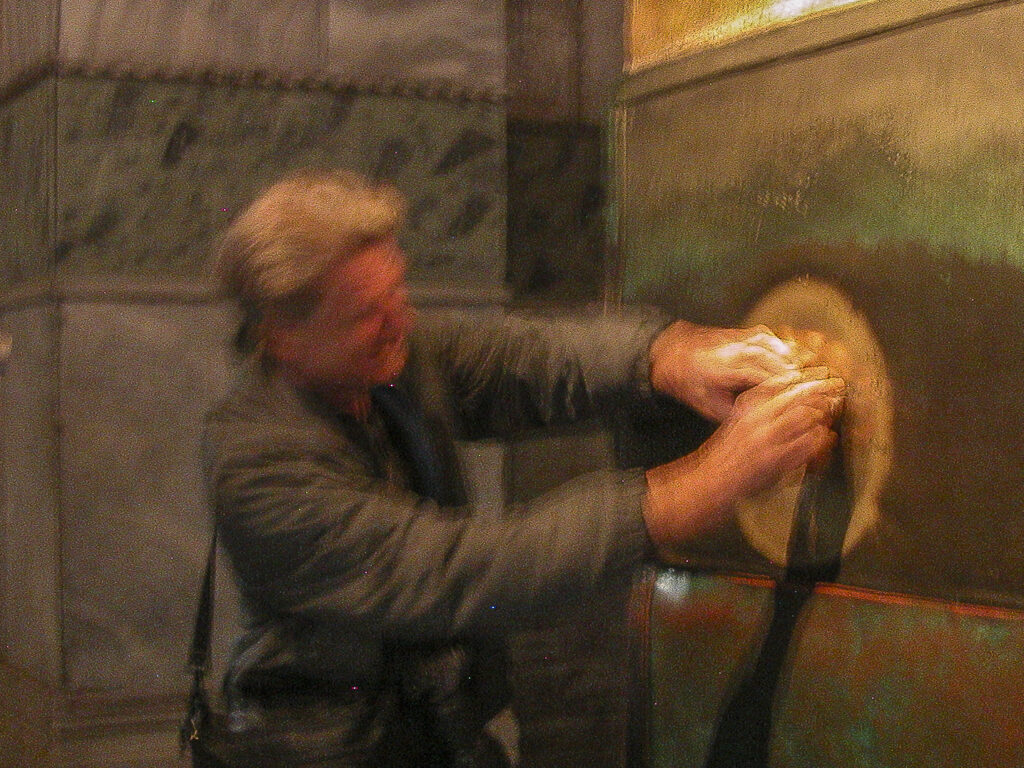

Several of our party tried putting their thumbs into the hole in the Wishing Column. David Lindquist was one of them. I don’t know what he wished for, but he wasn’t sick at the time, so he couldn’t make a valid test of the putative health-giving properties of the column. (Note: David has since passed away, and this post is dedicated to him in memoriam.)

Sandie also tried her luck at the Wishing Column. This was a very dimly-lit corner of Hagia Sophia, and my camera wasn’t able to take in enough light at the speeds required to freeze motion, so my pictures here came out blurred and indistinct.

Not to be outdone, Cherie made a great effort to ensure that she rotated her hand 360 degrees around the hole, in an agonizing attempt to defy the limits of human anatomy. I also tried the column, and I can now authoritatively state that the legend is not trustworthy. I wished for world peace and the end of international strife, and, well….

Sultan Murad III, who reigned from 1574 to 1595, began his reign by having his five brothers strangled, according to Ottoman custom. Sometime during his reign he also stole from Pergamon two huge alabaster lustration (ritual purification) urns, carved during the Hellenistic era from single blocks of marble, and installed them on the sides of the nave in Hagia Sophia. David Lindquist posed by one of them with his mascot bear Hero (which also became the mascot of our entire tour group during this trip).

The half-dome over the apse, at the east end of Hagia Sophia, features the Virgin and Child mosaic, which depicts the Virgin Mary sitting on a throne holding the Christ Child on her lap.

Theotokos is a Greek term meaning “the one who gave birth to God.” The dating of the Theotokos Virgin and Child mosaic is uncertain; it may be a ninth-century reconstruction of an original sixth-century mosaic destroyed during the iconoclastic period, but it also could be a restoration from a later time. Nobody knows for sure.

When the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453, they converted Hagia Sophia into a mosque, replacing Christian appurtenances with Muslim ones. In the apse, the altar and iconostasis (icon wall) gave way to a mihrab and minbar. The mihrab is a niche in the wall of a mosque indicating the qibla, the direction of Mecca, toward which believers must kneel when praying. The minbar is a pulpit from which the imam delivers sermons. The Christian mosaics depicting Jesus, Mary, the saints, etc. were removed or plastered over in accordance with the Islamic prohibition on representations of humans and animals. The stained-glass windows in the apse now display Islamic inscriptions in elegant calligraphy instead of Christian imagery.

The present-day appearance of the apse is largely a product of the restoration of 1847-49 carried out at the behest of Sultan Abdulmejid I by the Swiss-Italian Fossati brothers. They made some structural repairs and reinforcements, rejuvenated many of the decorations, renovated the minbar and the mihrab and built a new hexagonal loge for the Sultan. With the permission of the sultan, they also did exploratory work on the mosaics, rediscovering and exposing some of the great Christian mosaics plastered over after the Ottoman conquest. But in most cases, in accordance with the Sultan’s wishes, after uncovering the mosaics they documented them and then painted over them again. It was not until after 1935, when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk turned Hagia Sophia a museum, that the mosaics could be restored to public view.

In the center of the apse is the mihrab, the niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, i.e. the direction of Mecca, toward which Muslims should face when praying. In Hagia Sophia, it occupies the same spot as the Christian altar before the Turkish conquest. The two giant candlesticks on either side of the mihrab were donated by Grand Vizier Ibrahim, who pillaged them from the Hungarian court church during the Turkish conquest of Buda in 1526.

The minbar or pulpit, from which the Imam delivered sermons on Fridays, was first added to Hagia Sophia during the reign of Murad III (1574–1595), but the current one is a product of the renovation of 1847-1849.

Looking up from the ground floor into the vault of one of the exedrae, I was doubly impressed by the way in which these semicircular recesses provide a pleasing way to round out what would otherwise be a stark and abrupt junction between the gallery sides.

Feral cats were a common sight in Hagia Sophia. I thought they provided a nice touch of warmth and coziness in contrast to the cold stone walls and floors of the cath…er, I mean, mosque. I imagine that they were tolerated as an economical means of keeping down the rodent population as well.

Sultan Mahmud I added a library to Hagia Sophia in 1740. It included benches for reading and stands to hold books for readers sitting on the benches.

A series of elegant grilles separate the library from the nave.

In the library stood a piece of furniture which greatly intrigued us. There was nothing to identify its provenance or purpose, and we could only speculate on who made it, when and why. One might guess that it provided light to read by, but the light in the dome seemed too dim to be adequate for that purpose. Even with the illumination from the window, the library was so dark that Sandie’s camera could only capture the picture with a very low shutter speed, so the result is somewhat indistinct; but I was so impressed by the piece that I couldn’t resist including it here.

On our way to the exit we trod marble steps which were worn down by many centuries of foot traffic passing over them.

We exited Hagia Sophia through the Southwestern entrance, another monumental doorway, with a mosaic in the tympanum (archway over the door), depicting the Virgin Mary seated in the center with the Christ child on her lap, with Emperor Constantine on her left, presenting a model of the city of Constantinople, and Emperor Justinian on her right, presenting a model of Hagia Sophia. This mosaic dates from the reign of Basil II (976-1025), one of the most powerful Byzantine emperors, at a time when Byzantium was at the height of its economic and cultural ascendancy.

The figure of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child in the mosaic closely resembles the one in the mosaic on the semi-dome of the apse, pictured earlier, and was likely copied from it. This mosaic was plastered over after the Ottoman conquest, and rediscovered during the restoration of 1847-49.

Exiting from the southwestern entrance, we passed the Muvakkithane, or Timekeeper’s Station. The muwaqqit or timekeeper is the person – ideally an astronomer – whose duty it is to determine the correct time for Adhan (ezan in Turkish), the call to prayer. The Fossati brothers added the Timekeeper’s Station to Hagia Sophia as part of the renovation of 1847-49, in the reign of Sultan Abdulmajid. The renovation also involved (in addition to the interior modifications already described above) altering the minarets to make them equal in height.

After exiting Hagia Sophia, we passed by this beautiful Şadirvan (fountain for ritual ablutions), added by Sultan Mahmud I in 1740. Its rococo style is reminiscent of the Tulip Period, although that had supposedly ended a decade earlier.

At the time of our visit in 2006, Hagia Sophia was a museum, having been made so by a decree of the first president of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, in 1935. In 2020, the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan converted Hagia Sophia back into a mosque. This action evoked massive protests from Christian and secular commentators around the world, though Muslims generally supported the conversion, and the Turkish government staunchly defended its position. I’ll refrain from expressing any opinions on the subject, but I will note that so far Hagia Sophia has remained open free of charge to visitors of all faiths except during Muslim prayer times, during which Christian imagery is obscured by curtains or lasers, but otherwise continues to be visible, and the Turkish government has promised to continue to protect the mosaics and other Christian images.