When we arrived in Istanbul on the morning of March 30, 2006, we found that the mostly sunny and balmy weather we had enjoyed on our travels from Izmir to Side had given way to clouds and rain.

Our first stop in Istanbul, even before checking into our hotel, was Kandilli Observatory, or more precisely Kandilli Observatory and Earthquake Research Institute, which is located in the Kandilli neighborhood of the Üsküdar district on the Anatolian (Asian) side of Istanbul, atop a hill overlooking the Bosporus.. We stopped there first because the airport is also on the Asian side and the observatory was more or less on the way to the hotel. The observatory belongs to Boğaziçi University, a major research university in Istanbul.

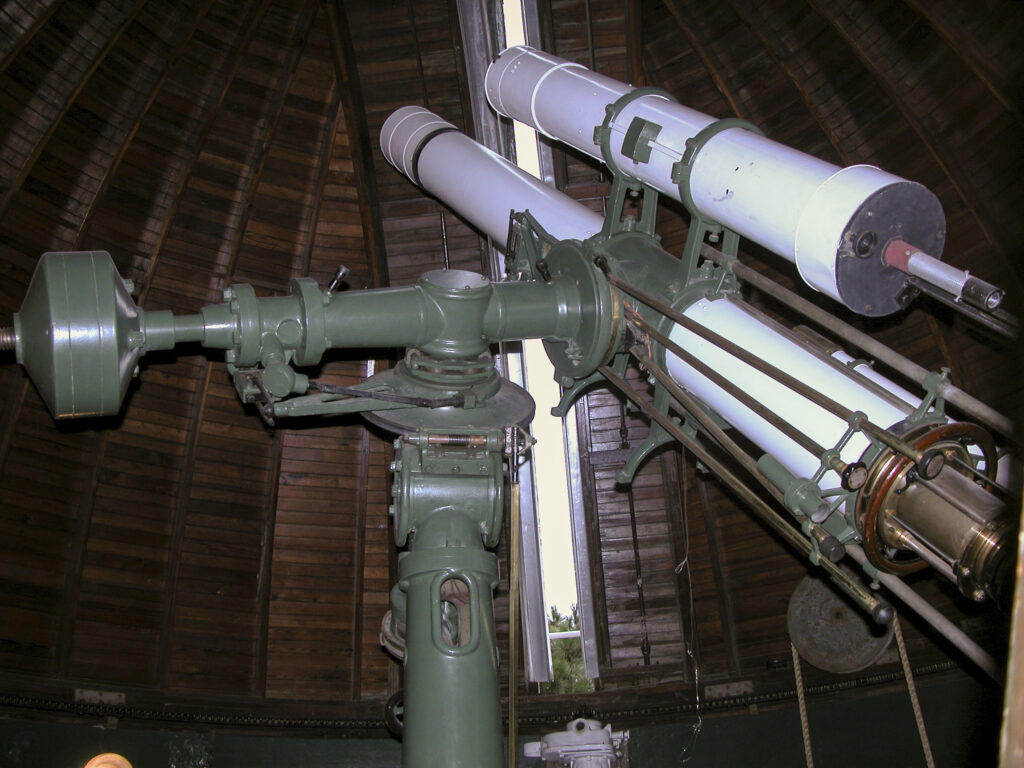

Kandilli has a 200 mm (7.87 inch) aperture Zeiss refractor mounted on an equatorial drive installed in a dome at the observatory building. It was purchased in 1918, but delivery was held up until 1924 because of the calamitous circumstances following the end of World War I. The observatory was not completed until 1935, and only then did the telescope go into operation. Initially it appears to have been devoted to solar observation and research. It was only the third research telescope delivered to Turkey; the first was destroyed in a fire during the Crimean War, and the second was a small (80mm) scope housed in an observatory which was destroyed in a riot in 1909, though the scope itself appears to have survived and ended up in a high school.

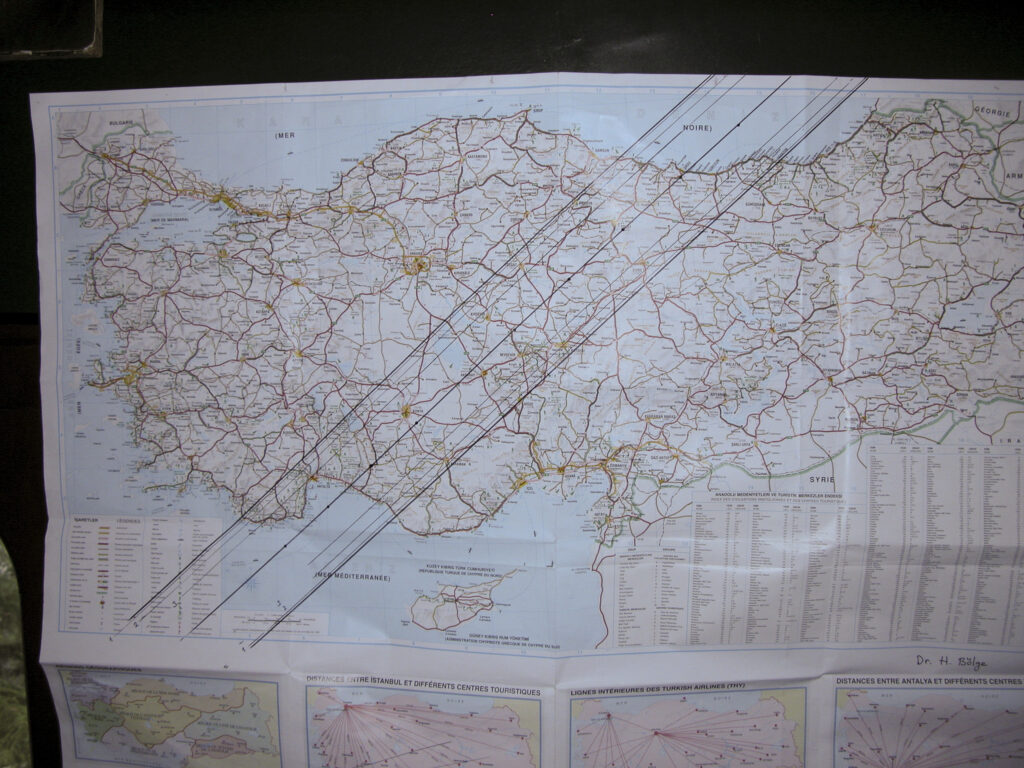

Turkey has come a long way since then. The country has a number of high-profile research observatories, such as TÜBİTAK National Observatory near Antalya, with a 1.5 meter reflector, and the new Eastern Anatolia Observatory (DAG) in Erzerum Province, with a 4-meter infrared telescope made in Italy, scheduled for “first light” at the end of 2022.

From the observatory, we crossed over to the European side of the city and checked in to our hotel, the Richmond. Located on Istiklal Street in the Beyoĝlu district of Istanbul, the Richmond was well-placed to optimize our navigation of the city.

We didn’t linger at the hotel for long; the sights of Istanbul beckoned, rain or no rain. Soon we were back on the bus, headed for Sultanahmet Square, in the heart of old Constantinople.

In old Byzantium it was the Hippodrome, the horse track, the center of the city’s social life. Chariot-racing was not just a spectator sport; it was a serious business, with major political ramifications. Each team was supported by a faction in the Senate, and competitions between teams became entangled with political and religious rivalries. In 532 CE the famous Nika riot between the supporters of the leading teams, the Blues and the Greens, escalated into a virtual civil war that resulted in the deaths of 30,000 people and the destruction of much of the city, including the Hagia Sophia cathedral. Emperor Justinian had the cathedral rebuilt, and his version is the one still standing today.

We got our first glimpse of Hagia Sophia from Sultanahmet Square on this rainy March morning; but our schedule for that day directed us elsewhere, so our visit to the cathedral had to wait.

Two Egyptian obelisks stand in Sultanahmet Square. One was originally erected at Karnak in Egypt by Pharaoh Thutmose III in the 15th century BCE, and moved to Constantinople by Roman Emperor Theodosius I in 390 CE.

At the end of the square opposite the Obelisk of Theodosius I stands the Walled Obelisk. The date of its original construction is unknown; it may have also built in the time of Theodosius I. It is also known as the Constantine Obelisk, after the 10th century Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, who had it restored and coated with bronze plates. These were plundered by the Latin occupiers during the Fourth Crusade, and now only the stone core remains.

Next to the Hippodrome stands a structure no less imposing than Hagia Sofia: the Blue Mosque, officially known as the Sultan Ahmed mosque. In the early 17th century the Ottoman Empire suffered a series of military reverses at the hands of the Habsburg Holy Roman Empire and the Safavid Persion Empire, and Sultan Ahmed I, the namesake of Sultanahmet Square, saw these setbacks as an omen that he was losing the favor of Allah. In order to win it back, and to reassert the glory and majesty of the Ottoman empire, he decided to build a new mosque that would rival Hagia Sophia as a work of art and engineering. The Blue Mosque, begun in 1609 and completed in 1617, was the result.

The architect of the Blue Mosque, Sedefkâr Mehmed Ağa, was the last student of the master architect of Suleiman the Magnificent, Mimar Sinan, considered the greatest exponent of the Ottoman classical style. This style combines elements of Byzantine and Islamic architecture, and you can clearly see the resemblance to Hagia Sophia.

Sultan Ahmed I’s predecessors had traditionally paid for their building programs with the spoils of their conquests, but he had no loot to show for his mostly unsuccessful wars, so he had to raid the public purse to pay for the Blue Mosque. This caused an uproar among the Islamic ulama (Muslim religious authorities), who were also scandalized that it had as many minarets as the Grand Mosque in Mecca. Sultan Ahmed partially assuaged their ire by causing a seventh minaret to be built for the Grand Mosque in Mecca.

The front portals as well as the interior are decorated with verses from the Koran, many of them the work of Seyyid Kasim Gubari, considered the greatest Ottoman calligrapher of his time.

In addition to the six minarets, the Blue Mosque has five main domes and eight secondary domes. It was built on the site of the Grand Palace of the Byzantine Emperors.

The forecourt is as large as the mosque itself and is surrounded by a continuous vaulted arcade.

Only the Sultan was permitted to enter the gate to the forecourt on horseback; others had to walk. But even the Sultan had his constraints; a large chain was stretched across the gate at such a height that when he rode through, he would have to duck his head by way of showing his humility before Allah. I doubt that this act of abasement had the effect of curbing any sultan’s ego with respect to his fellow mortals, however.

The four minarets at the corners of the mosque itself have three balconies each, whereas the two at the end of the forecourt only have two balconies. It must have been an onerous chore for the muezzins to climb the spiral stairs five times a day to make the call for prayer from these balconies; on the other hand, it was a good way for them to keep in shape.

Flash photography is not permitted in the Blue Mosque. Even though artificial lighting supplements the natural light admitted through the stained-glass windows, it was still too dim for our cameras inside the mosque, so many of our pictures came out blurry.

Since the Blue Mosque is a working mosque as well as one of the main tourist attractions of Istanbul, just as in Christian churches there are rules of etiquette, some of which have the additional purpose of facilitating the preservation of the site. Our guide Attila made sure we were properly instructed in the rules and gave us a brief rundown on the history and architecture of the mosque.

Visitors are required to remove their shoes and carry them in a bag, which is provided free of charge. (This practice is followed in many historic sites, e.g. the Imperial Russian palaces of Pavlovsk, Tsarskoe Selo, etc.) Both men and women are expected to dress modestly (no short pants or miniskirts), and head coverings for women are mandatory. Flash photography is disallowed and taking pictures of worshipers praying is discouraged. Quiet and respectful deportment is expected.

Carpeting in the Blue Mosque was equal to the most beautiful and lavish we had seen in Denizli. Of course, with many visitors passing through constantly, the carpets wear out quickly and have to be replaced often. Donations from worshipers, and I would hope also the donations (encouraged though not required) made by infidel visitors like us, pay for the new carpets.

The interior of the Blue Mosque is lined with 20,000 ceramic tiles, made in Iznik, a city 90 kilometers (56) miles southeast of Istanbul. In ancient times the city was known by its Greek name of Nicaea, where in 325 CE the Nicene Creed, one of the defining documents of Christianity, was adopted. During Ottoman times it was famous for the production of elegant ceramic tiles. Sultan Ahmed fixed the price of ceramic tiles by decree and made no provision to compensate for inflation over the eight years of construction, with the result that the quality of the tiles in the Blue Mosque is said to be somewhat uneven. However, I didn’t notice this myself.

The arches over the doorways and alcoves are a feature of Islamic architecture that I find particularly attractive. I was later to find very similar constructions in Moorish buildings in Spain, most notably the Great Mosque of Cordoba.

The main dome of the Blue Mosque is quite striking, but it is sometimes compared unfavorably to the central dome of Hagia Sophia because it is supported by four stout pillars, whereas Hagia Sophia’s central dome is anchored by “pendentives” which distribute its weight on the walls of the cathedral. The next picture doesn’t show the pillars, but you can see them in the two following.

The mosque has over 200 stained-glass windows. The glass for the windows was a gift from Venice to the Sultan. Venetian glass, made on the island of Murano in Venice’s lagoon since the 13th century, was the finest available. There is some irony here: after plundering the treasures of Christian Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, the Christian Venetians later bestowed their largesse on the city’s Muslim conquerors.

Supposedly ostrich eggs were put on the chandeliers to repel spiders and thereby keep them free of cobwebs. I don’t know why ostrich eggs would repel spiders, but I’m not able to put that notion to the test because ostrich eggs are hard to come by in Southern California. In any case, I saw neither ostrich eggs nor cobwebs. I suspect that nowadays the cobwebs are taken care of by the cleaning crew.

In the southeastern corner of the Blue Mosque there was an area reserved for the Sultan and his retinue. It contained a loge, where the royals could be seen by the public, and several secluded rooms, to which they could retire when they wanted privacy.

The Janissaries were the elite infantry of the Ottoman Empire, the household troops of the sultan. They were recruited via a levy known as the devşirme, which was in effect a tax on the empire’s Christian subjects whereby their male children of ages from 6 to 14 were taken from them, converted to Islam, given rigorous military training and subject to strict disciplinary rules. They were forbidden to engage in trade or to marry before age 40. They were a formidable and feared military force, but as time went on, their discipline was relaxed, they acquired excessive power and privileges, and ultimately became a kind of praetorian guard, making and breaking sultans, and acting as a reactionary barrier to progress. Eventually, in 1826, Sultan Mahmud II issued a decree disbanding the corps. This provoked the last of their many mutinies, in which the Sultan used artillery to kill 4,000 of them and then beheaded the rest. During the revolt, the Grand Vizier made the retiring rooms in the Blue Mosque his headquarters for directing the suppression of the rebels.

I found the Blue Mosque a magnificent and overwhelming architectural masterpiece, but I have heard that it is only one of several equally stunning mosques in Istanbul. I wish I had been able to tour some of the others, but there are just too many amazing sights to see in Istanbul and even in three days we didn’t have time to tour more than a small fraction of them.