Sultan Mehmet II began the construction of the Topkapı Palace in 1459, six years after conquering Constantinople. Since he already had a palace by then, the new palace was called – surprise – the New Palace. It was not called Topkapı, which means Cannon Gate, until the 19th century. Mehmet’s successors greatly expanded the complex, adding many new structures as well as restoring and remodeling existing ones.

Topkapı served as the Sultan’s primary residence as well as the headquarters of the Ottoman Empire’s government until the mid-17th century. After that the Sultans migrated to new palaces along the Bosphorus and the government functions were relocated elsewhere. In 1856 Sultan Abdulmejid I made the transition official by moving the court to his newly built, European-style Dolmabahçe Palace (I’ll deal with that also in another post). In 1924, after the Ottoman Empire gave way to the Turkish Republic, the government made Topkapı a museum. Only a few of its hundreds of buildings and rooms are actually open to the public at any given time, but the palace is so huge that even that fraction is overwhelming. It was impossible to record and report on everything we saw and experienced, so this account can provide only a brief glimpse into the wonders of the place.

The Topkapı Palace has four courtyards. The First Courtyard, also known as the Court of the Janissaries or the Parade Court, was a parklike area where janissaries paraded and provided an outer buffer of security for the Sultan. It also contained the Church of St. Irene, the Imperial Mint, and various other governmental offices. The Second Courtyard enclosed the palace, properly speaking, i.e. the area where the Sultan lived and the business of government was conducted. The Third Courtyard was also called the Inner Palace and was the Sultan’s private domain. The Fourth Courtyard was a more private inner sanctum, also called the Inner Sofa, containing pavilions of various kinds, gardens and terraces. I shall deal with the Third and Fourth Courtyards in the next post, along with the Harem.

The Bâb-ı Hümâyûn – Imperial Gate – provides entrance to the First Courtyard. It was previously known as the bab-i ali, or High Gate, and its French translation (French being the language of diplomacy in those days) became used throughout Europe a synecdoche, or metaphor, for the Ottoman government as a whole: the Sublime Porte, or most often just the Porte. This derived from the Byzantine and Ottoman practice of issuing decrees and announcements at the gate of the palace.The Topkapı Palace has four courtyards. The First Courtyard, also known as the Court of the Janissaries or the Parade Court, was a parklike area where janissaries paraded and provided an outer buffer of security for the Sultan. It also contained the Church of St. Irene, the Imperial Mint, and various other governmental offices. The Second Courtyard enclosed the palace, properly speaking, i.e. the area where the Sultan lived and the business of government was conducted. The Third Courtyard was also called the Inner Palace and was the Sultan’s private domain. The Fourth Courtyard was a more private inner sanctum, also called the Inner Sofa, containing pavilions of various kinds, gardens and terraces. I shall deal with the Third and Fourth Courtyards in the next post, along with the Harem.The Bâb-ı Hümâyûn – Imperial Gate – provides entrance to the First Courtyard. It was previously known as the bab-i ali, or High Gate, and its French translation (French being the language of diplomacy in those days) became used throughout Europe a synecdoche, or metaphor, for the Ottoman government as a whole: the Sublime Porte, or most often just the Porte. This derived from the Byzantine and Ottoman practice of issuing decrees and announcements at the gate of the palace.

The Bâb-ı Hümâyûn is adorned with verses from the Qur’an and tughras (calligraphic monograms) of the sultans in gilded Ottoman calligraphy. The tughra on the archway is that of Sultan Abdülaziz, who renovated the gate in the 19th century.

The protection of verses from the Qur’an was reinforced by Turkish Green Berets. Some years after our visit, on November 30, 2011, a Libyan terrorist attempted to emulate the achievements of the Norwegian madman Anders Breivik, who killed 77 people on July 22 of that year, by attempting to stage a similar massacre in Topkapı Palace. He got no further than the Bâb-ı Hümâyûn, where the guards, observing that he carried two hunting rifles, stopped him. However, he did succeed in wounding the two guards at the gate and evading them briefly, until he encountered other guards, who drove him back to the gate, where he hid out until a Turkish SWAT team arrived and put him out of his misery. After that incident, additional security measures were implemented, though I haven’t been able to find out the details. The contrast between this outcome and the Norwegian massacre illustrates the principle that if you’re a terrorist who likes to murder innocent people, you may want to consider operating in some country other than Turkey.

Passing through the Imperial gate, we proceeded down a pleasant tree-lined lane through the First Courtyard toward the Gate of Salutations, the entry to the Second Courtyard.

On the left while passing through the First Courtyard, one encounters the Basilica of Hagia Irene, the original of which was completed in the reign of Constantine the Great. However, like much of the rest of the city, it burned down in the Nika riots of 532 and had to be rebuilt. It has been restored several times since. It was one of the few Christian churches not converted into a mosque after the Turkish conquest; instead the Ottomans used it first as an arsenal, later converting it into a military museum, which it remained until 1978. At that time it was turned over to the Ministry of Culture, and nowadays it is used as a concert hall in addition to serving as a museum in and of itself.

If one turns to the right after emerging from the Imperial Gate, upon reaching the courtyard wall one encounters the Fountain of the Executioner. According to legend this is the place where the Sultan’s headsman washed the blood off his sword and hands after lopping off a victim’s head. I have not been able to verify whether this legend is true. As far as I know, the Sultans preferred to execute people by having them garroted.

Traversing the First Courtyard, one arrives at the Gate of Salutations, or Middle Gate, leading to the Second Courtyard (also known as Divan Square) and the Palace proper. Only the Sultan (and, according to some sources, his mother, though I’m not sure that the palace women actually rode horses) was allowed to pass through this gate on horseback; everyone else had to walk.

On the south side of the Second Court are the palace kitchens, to which we proceeded first after passing through the Gate of Salutations. The kitchen area constituted almost a palace in itself, incorporating not only food storage and preparation areas but also dormitories, baths, and a mosque for the cooks, a harem (whether for the cooks’ families or the female servants, or both, I don’t know) and even a school.

The kitchen complex contained ten domed buildings, arranged in two rows with a narrow street or courtyard separating them. It was originally built in the 15th century and expanded during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. Heavily damaged in a fire in 1574, the complex was then remodeled by the court architect, Mimar Sinan.

Nowadays, the kitchens are not used to prepare food but to house museum exhibits. These include a collection of tens of thousands of pieces of fine Chinese, Japanese and European porcelain. I neglected to photograph the porcelain because there was too much to do it justice in the time we had, it was too hard to decide which pieces to photograph, the exhibit rooms were dark and flash photography was not allowed. Sandie did take some shots of the porcelain, but they came out very blurry, so I haven’t posted them here.

There was also a wonderful collection of silver in the form of gifts presented to Sultans over the years, and I did have some success shooting a few of them. One was this exquisite replica of the Fountain of Sultan Ahmet III located near the Imperial Gate.

I love maps in general, and I was mightily attracted by this silver globe. I wanted to take it home with me, but the museum guards were unenthusiastic about that idea.

I also favored this vessel (chalice? bowl? I’m not sure what to call it) presented to Sultan Abdul Hamid II on the 25th anniversary of his accession to the throne, in 1901, by whom I don’t know.

My favorite item in the silver collection was a gilded bird cage which reminded me of some lines from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam:

Come! And in the fires of spring

The Winter Garment of repentance fling;

The Bird of Time hath but a little way to fly,

And Lo! The Bird is on the Wing!

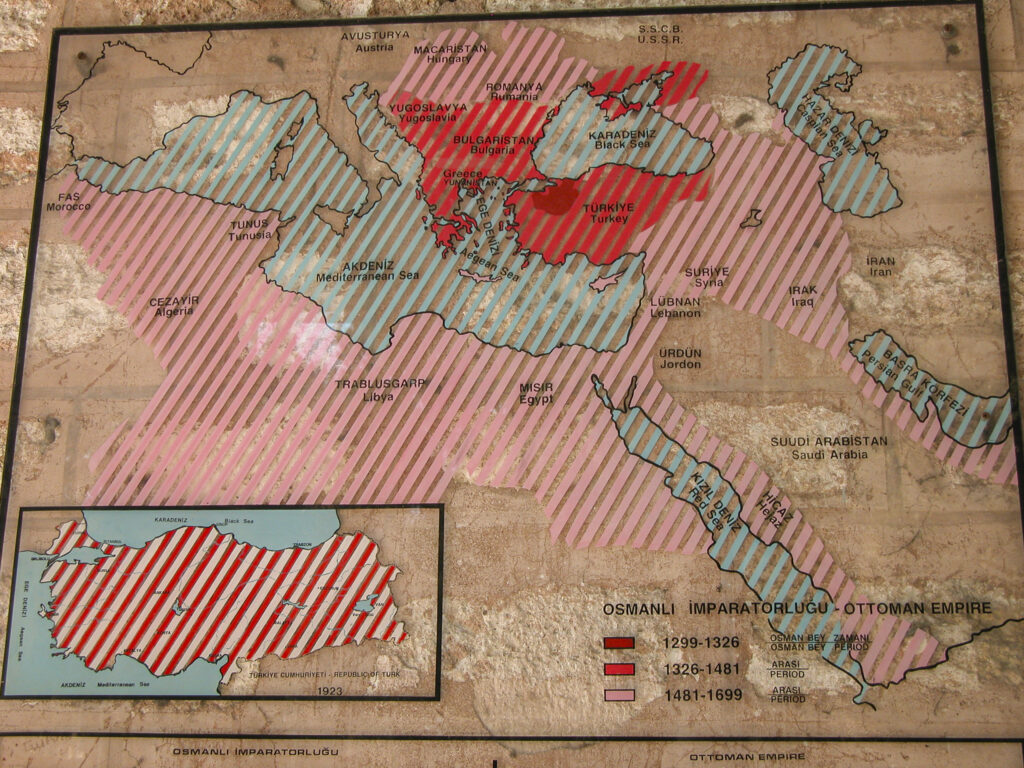

Somewhere in the kitchens, if I remember correctly, we also encountered this map showing how the Ottoman Empire expanded from its early days at the beginning of the fourteenth century CE, when it occupied just a small area of Anatolia and the Balkans (solid deep red patch), to the conquest of the former Byzantine Empire in the Balkans and Anatolia in the fifteenth (red diagonal striping), and thence to control most of the Near East and North Africa, not to mention Hungary, Transylvania and Moldavia in the fifteenth (pink diagonal striping) – and also how it contracted in the twentieth as it became transformed into present-day Turkey (inset). Sic transit gloria mundi.

On the north side of the Second Court, opposite the kitchen complex, stand a very different set of buildings, of which the most important is the Imperial Council Chamber. This was the setting for the chief deliberative body of the Ottoman government, the Dîvân-ı Hümâyûn, composed of the Grand Vizier (a kind of prime minister) and the other ministers of the crown. It is usually just referred to as the Divan.

The present Imperial Council building dates from the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, but was rebuilt and remodeled many times thereafter, so it represents an amalgam of styles.

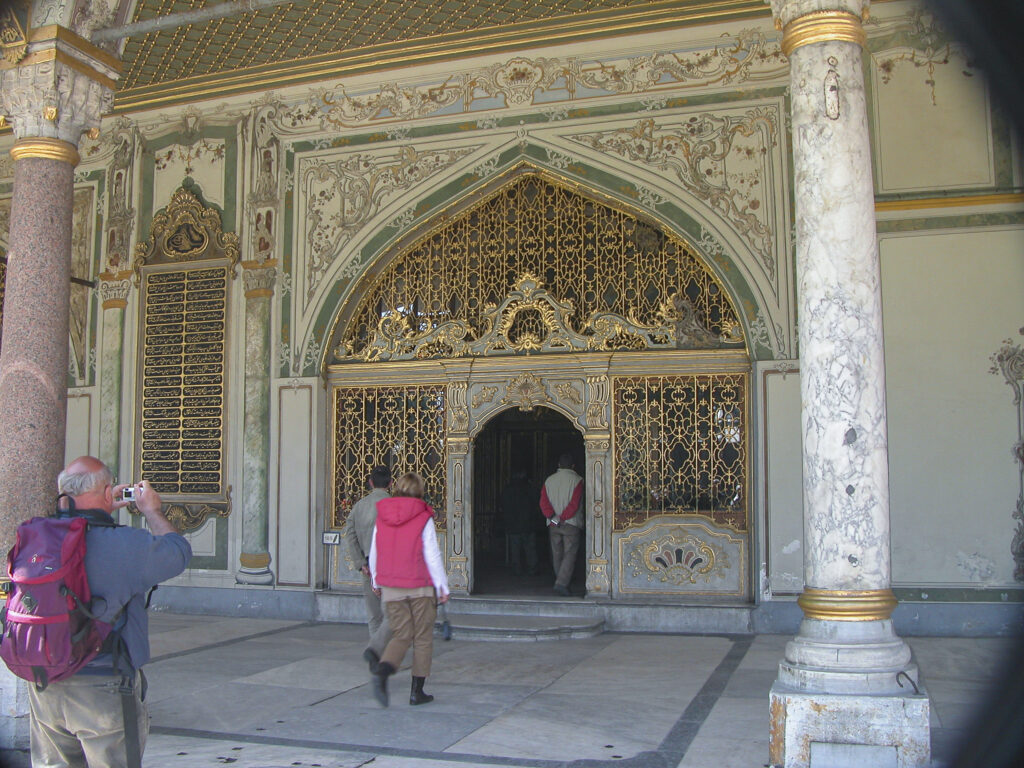

There are several entrances to the council hall, both from inside the palace and from the courtyard. The main courtyard entrance, through which we entered, is shown below. The marble and porphyry pillars holding up the porch are associated with the period of classical Ottoman architecture, while the rococo grilles and the wall and ceiling decorations are in the later rococo style of the 18th century.

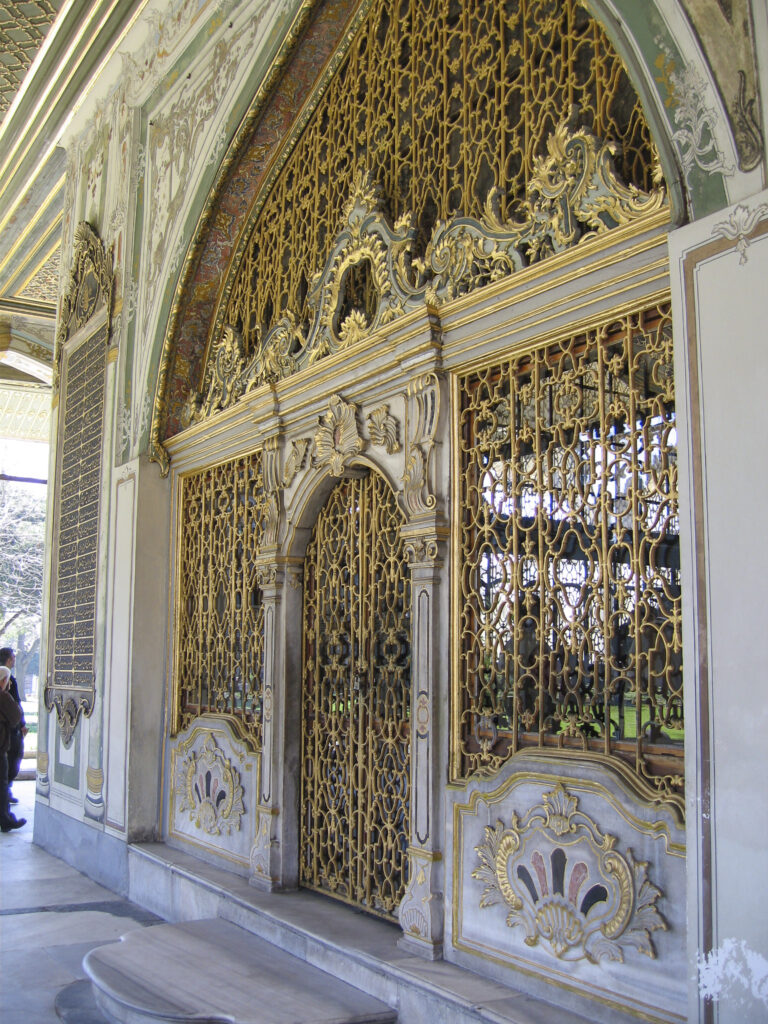

A close-up view of the golden grilles reveals that they allow light and air to pass freely into the Council rooms, and a person standing outside could easily observe and hear the discussions of the Divan inside while not being able actually to enter the building. This satisfied a legal requirement that Council sessions be open to the public.

The Divan building has three main chambers, each with its own dome: the Kubbealtı, where the Divan actually met; the secretariat, where the clerical staff worked; and the Defterhane, where the archives were stored. The domed ceiling of the Kubbealtı is framed in the photo below.

To be fully appreciated, the domed ceilings have to be viewed in the context of the supporting walls and arches; taken together, they impart an overwhelming atmosphere of opulence.

At one end of the Kubbealtı was a grille-covered window (kasr-ı adil) which overlooked the chamber; behind it was a loggia connected by a passage to the adjoining Tower of Justice, and thence to the harem. The Sultan, or his mother, the Valide Sultan, who was often the most powerful person in the palace next to the Sultan himself, could sit in the room behind the window and secretly monitor the Council’s sessions. Suleiman the Magnificent is said to have particularly favored its use.

Next to the Kubbealtı was the room where the secretaries did their work; its lower panels were workaday in comparison with the Kubbealtı, but the upper walls and dome were just as lavishly decorated.

For many years the Divan was the main executive body of the Ottoman Empire, overseeing both foreign and domestic affairs, and acting as a court of law as well. Its heyday lasted from the 14th to the first half of the 17th centuries, after which its importance began to decline, its powers being increasingly assumed by the Grand Vizier. In 1654 a new building was built, outside the Topkapı Palace, to serve as the residence and offices of the Grand Vizier. Like the Palace, this building had a monumental gate, and thereafter that building together with its gate became the new Sublime Porte. (The building now houses the offices of the Governor of Istanbul.) In the late 18th century, the Divan lost all its importance, and in the early 19th government reforms did away with it altogether. However, even as these developments were taking place, repair and remodeling of the Council building continued; the rococo wall and ceiling decorations seen below probably date from the renovations of 1792 and 1819.

The Tower of Justice (Adalet Kulesi), located between the Council Chamber and the Harem, is the tallest structure in the palace. From what I can gather it was built by Sultan Mehmet II and apparently served as the council chamber until Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha had the Imperial Council building constructed in the 1520s.

As we passed through the courtyards, we noticed a number of huge old trees that appeared to have lost most of their foliage and become hollow, as if they were dead. It turned out that they have fallen victim to a fungus that has completely hollowed out their trunks, yet they somehow survive and remain standing.

Years after visiting the Topkapı Palace, I read that in the Second Court there are cases where two trees of different species have grown together and effectively fused into one, without human intervention. Although Sandie probably wasn’t aware of it when she took the picture, the tree in the photo below appears to be one such self-grafting pair.

Next we explored the Third and Fourth Courtyards and the Harem, but for that you’ll have to see the next post.