Perge first came into history in Hittite times (before 1200 BCE) as Parha. Hundreds of years later, as a Pamphylian Greek city, it came under Persian rule until the conquests of Alexander the Great, and then fell under Seleucid domination. It most celebrated inhabitant was the mathematician Apollonius, a student of Archimedes, who lived there during the late third and early second centuries BCE.

Perge came under Roman rule in 188 BCE, and prospered thereafter. Proximity to the Kestros (now the Aksu) River gave it access to seaborne trade, until the silting-up of the river in late antiquity. Most of the surviving structures date from the Roman period. Perge also became an early center of Christianity; Paul the Apostle preached there, and by the 5th century CE the city had become the seat of a bishop. But it did not fare well during the Turkish invasions of the 11th century, and by 1000 CE it was abandoned.

A visit to Perge begins by entering through the Roman Gate, built in the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211 CE).

While passing through the Roman Gate, you get a view of the next portal, the much older Hellenistic Gate, which dates back to the 3rd century BC.

I don’t know why the Romans thought the city needed another gate; the Hellenistic Gate is arguably the most imposing structure in the city and would have been a formidable bulwark, far better suited to protect the city with its twin towers and its horseshoe-shaped courtyard at the back. The towers had three floors and were crowned by a conical roof.

In back of the Hellenistic Gate we encountered a horseshoe-shaped courtyard, not part of the original gate, but an expanse redesigned in 121 AD by Plancia Magna, daughter of the governor and priestess of Artemis, who decorated it with inscriptions and statues to honor the emperors and their relatives.

Near the Hellenistic Gate we encountered Roman baths, a Christian Basilica, the Agora, and a great deal of scattered rubble awaiting reassembly by archaeologists.

There were two sets of baths in Perge, a northern and a southern. Google Maps misidentifies a large structure northwest of the Hellenistic Gate as a 6th-century Byzantine basilica, but this was actually the Southern Baths, seen in the picture below. According to the text on a sign posted nearby, “These were Pamphylia’s largest and most magnificent baths. The people of Perge, after performing their physical exercises in the large palaestra, which was surrounded by porticos, rid themselves of their sweat in a cold pool and then entered the Frigidarium. From the architectural embellishments and statues revealed by excavations, this was obviously an outstanding structure. Subsequently the public went on to the Tepidarium and Caldarium, which were interconnected. The brick props used in the hypocaust system through which hot water was transmitted to these sections can be seen.” From what I know about ancient Roman baths, this has it partially backwards. The standard routine was to begin with the Tepidarium, which contained no water, but was merely a heated room where the warm air prepared one for the hot baths to come, and, upon returning, for the transition back to the cold air outside. (It was not a sauna, the ancient Roman counterpart of which was in a separate room called a laconicum.) The Tepidarium might also double as a place for undressing, or this might be relegated to another room called an apodyterium. From the Tepidarium, one proceeded to the Caldarium, the actual hot bath, then finally to the Frigidarium, which was a cold bath intended to close one’s pores in preparation for the return to the frigid air outside. Of course, practices varied among different provinces within the Roman Empire, and even among different establishments in the same area, but it seems more logical to take the cold bath last.

The on-site description continues, “It is said that in antiquity the public used the baths for both enjoyment and holding discussions. A fee was paid upon entry and the baths were used by women in the morning and men in the afternoon.” Some Roman baths, such as those in Pompeii, had separate facilities for men and women; but it has been noted that in Rome itself mixed bathing was common by the first century CE. One may doubt whether this was the case in the provinces, though.

Pictured below is a section of the southern baths. A “hypocaust” is a hollow space under the floor of an ancient Roman building, into which hot air was sent for heating a room or bath.

To the east of the Hellenistic Gate lies the Perge Agora. This a square area, dating from the 4th century CE, 65 meters on a side, surrounded by a stoa, a colonnaded portico with a covered walkway. It was in fact an ancient shopping mall, where the inhabitants could purchase all kinds of goods.

Looking north down the east side of the Agora afforded a view of the Acropolis, which dominates the northern part of the city. Traces of human habitation dating back to the Bronze Age (3300-1200 BCE) have been found there, but the structures visible today all are relics of late Roman or Byzantine times.

Systematic excavations of Perge began in 1946, led by Professor Arif Müfid Mansel, under the auspices of the Turkish Historical Society, and have been continued by his successors down to the present.

In the middle of the Perge Agora stands a large stone ring. I called it the “Perge Henge” because it reminded me of Stonehenge in England (which I’ve never visited). There were no signs or inscriptions to indicate its purpose, and for years I wasn’t able to find out anything more about it online. I speculated that it might be a pool into which virgins were thrown as a sacrifice to the gods, as in the ancient Mayan cities. However, recently I came across an article on the internet according to which the ring structure is now believed (presumably by archaeologists) to have contained a fountain.

Greco-Roman cities of this period were adorned with fine tile and splendid mosaics. I thought this elegant tile might have fallen from a ceiling that collapsed.

This marble tile at ground level on the side of a building fascinated me. If you look closely you can see a serpentlike figure and a knife carved in relief in the center. It shows up better in the next picture.

I don’t know whether the people of ancient Pamphylia ate snakes (people in southern China today consider them a great delicacy, and the more poisonous the tastier), but this could also be an eel, which they would certainly have eaten. So this is clearly a sign identifying a restaurant.

Perge occupies a very large area. It has a well-preserved theater and stadium, but these are somewhat removed from the main part of the city, and we skipped them since we had already seen the best-preserved theater at Aspendos and the most imposing stadium at Aphrodisia. At Perge the Agora, the Nymphaeum, the Baths and the main boulevard with its waterway were the focus of attention.

In one of the stoa shop doorways we encountered a couple of pirates who wanted to kidnap Sandie and sell her into a harem, but we managed to escape their clutches.

The main north-south street of Perge, called the Sütunlu Cadde in Turkish, extends 300 meters from the city gates to the foot of the Acropolis. In the middle ran a channel which supplied water to the fountains and baths. The city also had an underground sewer system, and many private houses also had indoor plumbing.

The water distribution system was quite sophisticated for its time. In the channels weirs (dams) had been built to regulate the flow of water and keep the level even.

While strolling up the main drag I encountered a column decorated with two human figures in relief, a male near the base (shown in the next picture) and a female higher up. There was no sign or inscription to identify the figures. I speculated that the lower one might be a city official offering a sacrifice to Artemis, patron goddess of Perge. But the same source that purported to identify the ringed structure in the Agora as a fountain also asserted that it might be Calchas, one of the mythical founders of Perge.

There was never any question about the identity of the female figure – it was clearly the goddess Artemis: she holds a bow, one of her identifying symbols; Perge was devoted to her worship and was famous as one of her chief shrines; and her image was stamped on coins minted in Perge.

I could not capture Calchas and Artemis in sufficient detail in one frame, so I had to shoot the column in segments.

Proceeding up the main drag, we headed for the Nymphaeum, the northern terminus of our exploration of the city, nestled at the foot of the Acropolis. The structure on the left in the photo below is probably the Palaestra, associated with the Northern Baths.

A palaestra could be a wrestling school, gymnasium or simply an exercise area, depending on local practice. It could be either a building or simply an open courtyard. In this case, it seems to have been a building constructed from travertine, but I’m not entirely sure, because the source I’m relying on also says that it was an open courtyard surrounded by changing rooms. The same source (Turkish Archaeological News) says that the palaestra was dedicated to Emperor Claudius by Gaius Julius Cornutus Tertullus, the husband of Magna Plancia. It’s hard to imagine a less athletic person than Claudius, and it’s unlikely that Plancia’s husband would have dedicated anything to Claudius, who reigned from 41 to 54 CE, whereas Plancia Magna and her husband were active much later, in the early second century. (They would not even have been born when Claudius was alive.) Plancia Magna made her important contributions to Perge mainly during the reign of the Emperor Hadrian, who reigned from 117 to 138, and her husband would likely have dedicated the palaestra to him – it was the custom to dedicate newly-constructed landmarks to the reigning emperor. Anyway, other sources say that the palaestra dated from 50 BC and was built by Gaius Julius Cornutus Bryonianus, who was probably the father of Plancia’s husband, and dedicated to Emperor Claudius by him. Bryonianus was a Roman senator and native of Perge.

The Acropolis loomed above as we neared the northern end of the main drag.

Near the Nymphaeum we encountered a drawing of how it was supossed to look, and did look, when it was built. Water was piped into it from hillside springs and flowed from underneath the reclining statue of Kestros in the center into the canal that ran downhill to the city gates.

Perge is located near the Aksu River, which in ancient times was known as the Kestros, which was also the name of its god. The Nymphaeum building is known as Hadrian’s Nymphaeium, but it was dedicated to Artemis of Perge, the Emperor Septimius Severus, his wife and his sons.

The statue in the arched window, however, represents not Hadrian or Septimius Severus or Artemis of Perge, but Kestros the River God – or so I’m told, since I wouldn’t be able to tell Kestros from Bacchus, especially without a head. So whose shrine is it?

As can be seen from the photos, since it was built the Nymphaeum has lost its second story, arches of the first-floor windows, the perpendicular side wings, the columns, and most of the statuary. Not only that, but the Nymphaeum should have nymphs. Where were they? It turned out that they were on their way.

When they arrived at the Nymphaeum, however, Sandie, Pam and Cherie found that a horde of savage barbarians had burst onto the site and were intent on pillaging the treasures it contained.

It turned out that the infidels were too late; other barbarians had been there first, and had spirited away the best of the treasures, including the two statues of Hadrian which had stood in the alcoves between the statue of Kestros, to the Archaeological Museum in Antalya.

Other barbarians had removed the head of Kestros the River God, as well as anything else worth taking.

Meanwhile, Sandie climbed halfway up the Acropolis above the Nymphaeum to get a fabulous panorama shot of the entire city of Perge.

From the Nymphaeum window above the statue of Kestros I took a picture of the main street and its waterway.

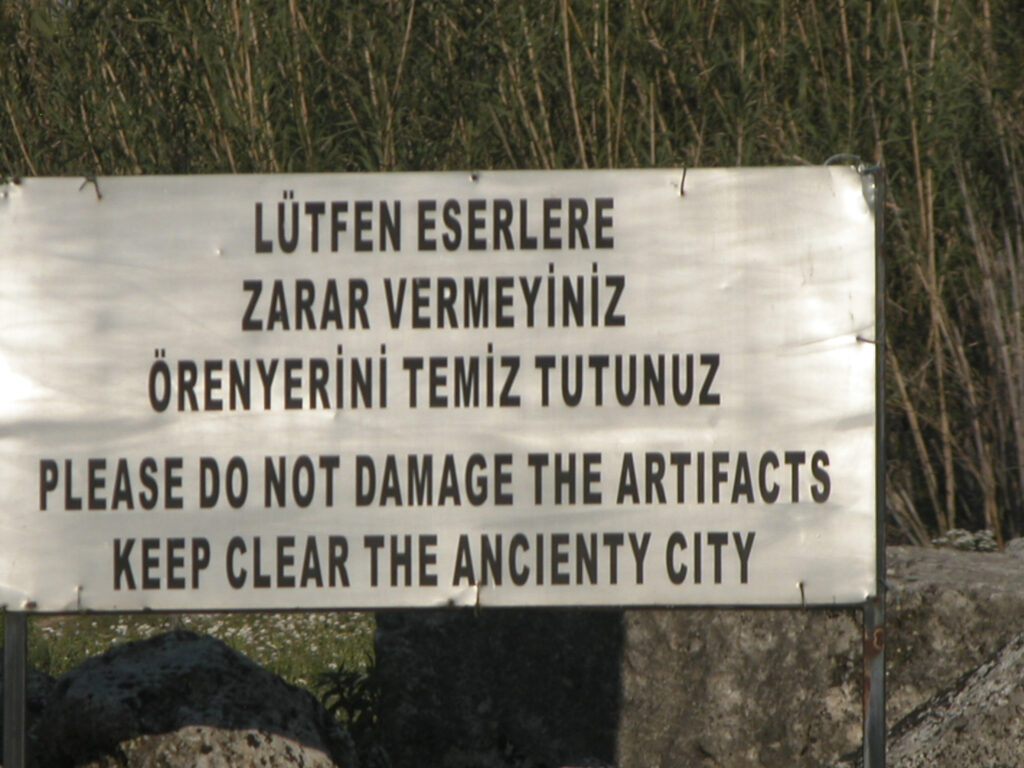

Somewhere along the way we stumbled across this placard imploring visitors in Turkish and English not to behave like barbarians.

As I wended my way back from the Nymphaeum, I snapped this view of the avenue by which we had come up.

Heading back to the gate, I passed a trio of fellow infidels, who, having pillaged the ancienty city, lounged nonchalantly among the ruins.