The Perot Museum of Nature and Science did not exist when I had previously been in Dallas, in 1992 and 2004. It was created in 2006 by merging three earlier museums, the Dallas Natural History Museum, the Dallas Science Place and the Dallas Children’s Museum; and in 2012 it opened in a new home, the building which currently houses it, in Victory Park on the outskirts of downtown Dallas. Construction of the building was financed entirely from private donations, the largest of which, $50 million, came from the five children of Ross Perot, the founder of Electronic Data Systems and two-time independent presidential candidate; hence the new museum was named for the Perots. Other donors also stepped up and brought the endowment to $185 million.

Designed by architect Thom Mayne, the Perot Museum structure is essentially a large cube standing on a large plinth (base), and has been described as “alluring but unsettling.” One possible source of this unease is a large (150 feet long) glass rectangle glued at about a 40 degree angle to the side of the building; this houses an escalator, affectionately known as the “T. rexcalator.”

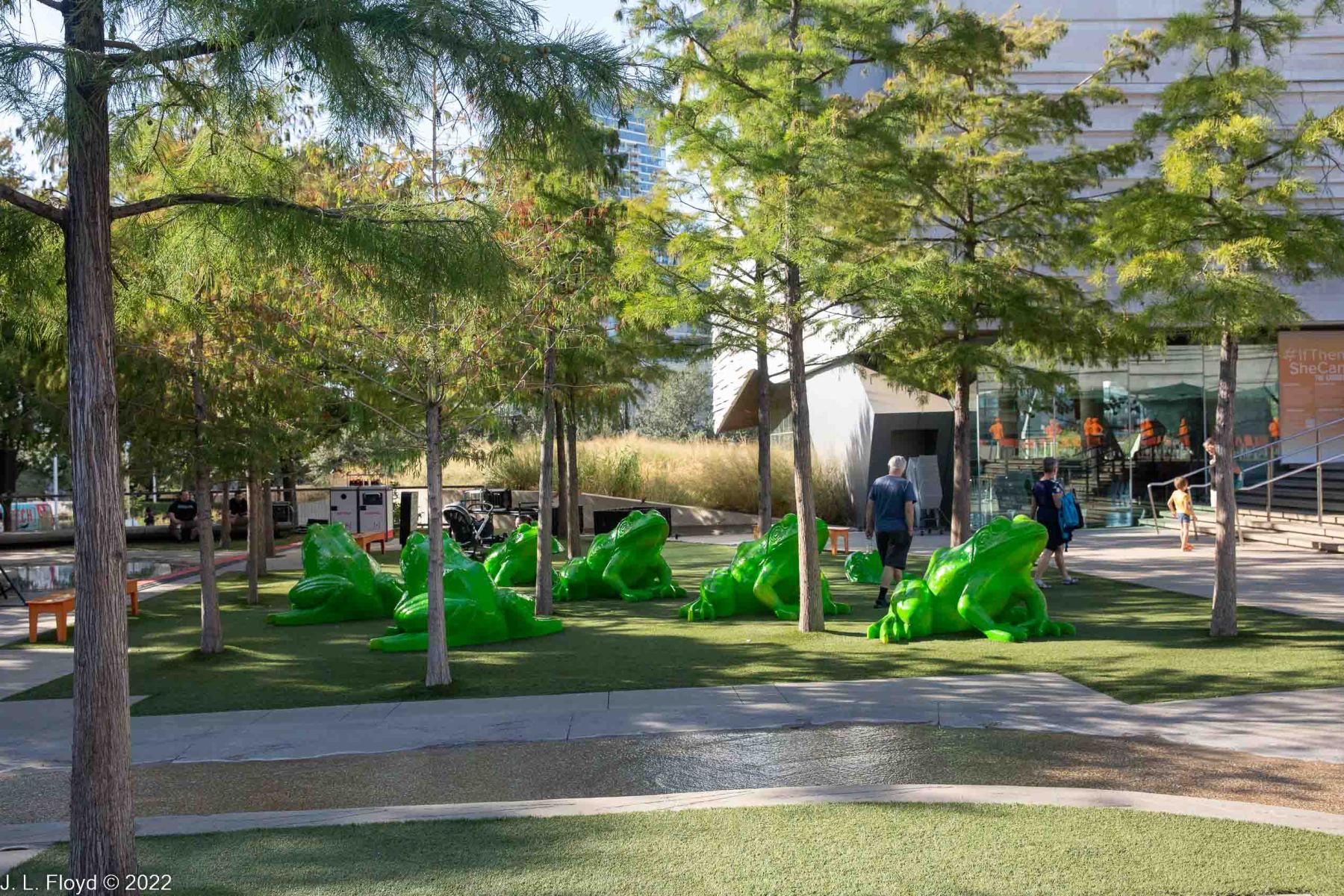

The Perot Museum is very proud of its sustainable and eco-conscious design. It uses advanced off-grid energy generation technology, including solar water heating. Low-wattage LED lighting is used throughout the building, aided by skylights directing sunlight into appropriate spaces. Landscaping is accomplished with drought-tolerant greenery, based on indigenous plants, fed by a rainwater collection system that captures runoff from the roof and parking lot.

Whatever one thinks of the architecture, the Perot Museum deserves a visit. There is a wide variety of permanent and temporary exhibits, devoted to astronomy, earth sciences, various branches of engineering, biology and life sciences, and even sports. But even though I’m an avid amateur astronomer, I was mostly interested in the paleontological exhibits, which are on display in the T. Boone Pickens Life Then and Now Hall, so I neglected most of the other attractions – all the more reason to go back for a return visit next time I’m in Dallas.

When you enter Pickens Hall, the first dinosaurs you see are the Tyrannosaurus Rex and the Alamosaurus sanjuanensis on display in the center. Before venturing further, I should note that when I make reference to a dinosaur, or other extinct prehistoric creature, I am usually talking about a skeletal reproduction. These are in general not actual fossils but replicas constructed on the basis of the actual fossil bones as well as imprints of bones. Although there are exceptions, the bones themselves are generally too fragile, fragmentary and precious to be put on public display, where they would be exposed to all kinds of pollutants in the air as well as vandalism and accidents. But paleontologists have become very skilled at reconstructing and replicating skeletons from even very incomplete specimens of actual bones, and the skeletal reproductions look identical to the real thing.

The Alamosaurus is colossal, the largest dinosaur ever discovered in North America, and it dominates the hall. It’s fitting that it should be on display in Texas, although it was first discovered in New Mexico in 1921. I should note that the Alamosaurus was not named for the Alamo in San Antonio, but rather for the Oso Alamo geologic formation in which it was found. This in turn was named after a New Mexico trading post, which in its turn was named after a tree: the word “alamo” means “poplar” in Spanish. Further, the name of the only species identified for the Alamosaurus genus, sanjuanensis, comes from San Juan County in New Mexico, where the Oso Alamo formation is located.

There are other interesting dinosaurs represented in the hall, too. I won’t write about the T. Rex because it’s too well-known, and there were others that I’d never heard of before and deserve to be better-advertised. There was Pachyrhinosaurus (meaning “thick-nosed lizard” in Greek), a centrosaurine ceratopsid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of North America. (Centrosaurine means pointed lizard in Greek and ceratopsid means “horn-faced” or beaked.) Three species of pachyrhinosaurus have been found in North America, two in Canada and one in Alaska. The third, most recently discovered, was unearthed by Perot Museum paleontologists in the Prince Creek Formation of Alaska in 2012, who had to climb a 300-foot riverbank in rain and snow to reach it. Anthony Fiorillo, who was curator of the Perot Museum at that time, named that species after the Perot family: Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum, in honor of their contributions to the museum. Pachyrhinosaurus was related to the famous three-horned Triceratops, but rather than having horns it had bony knobs on its face known as bosses.

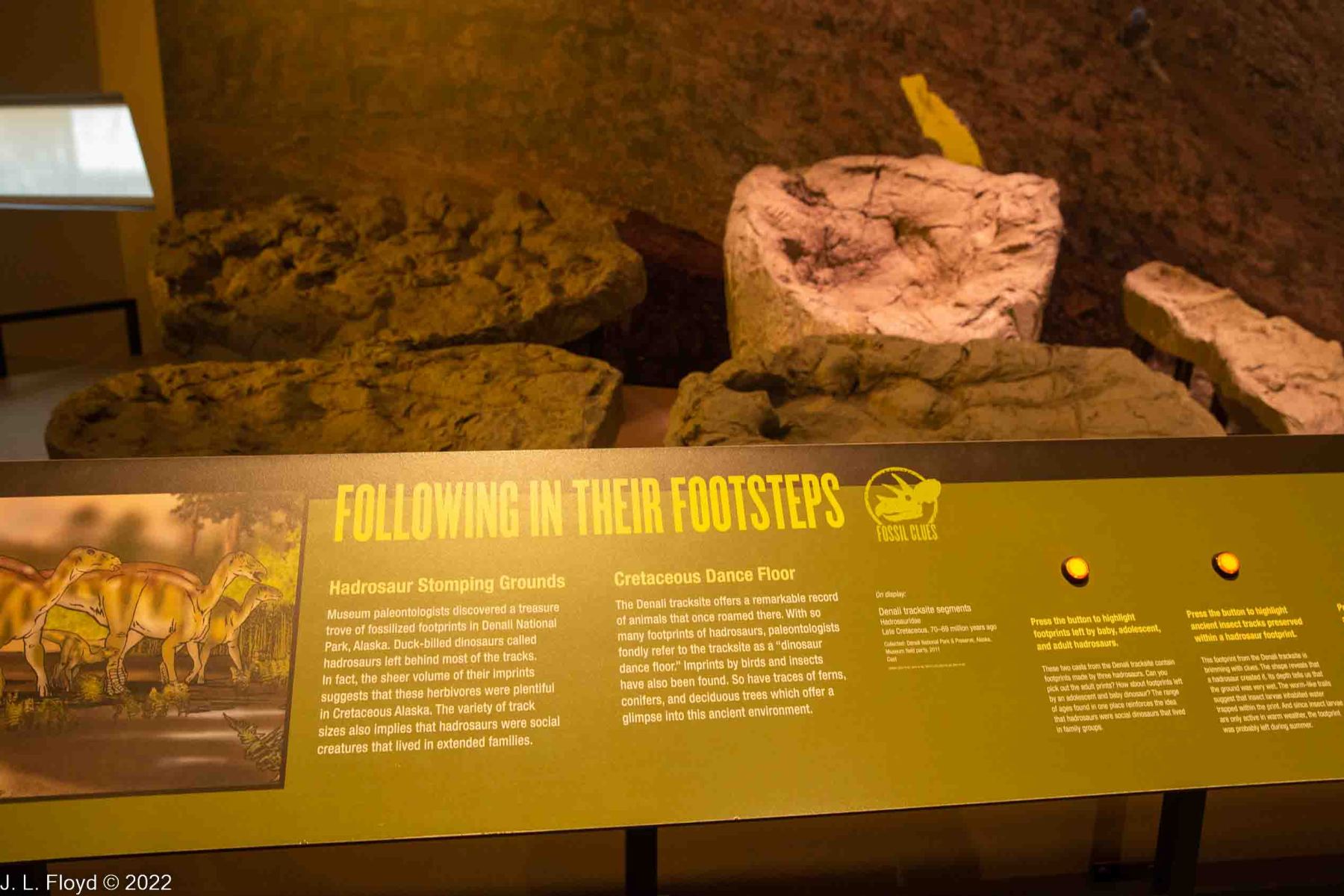

Not all fossils are bones. There is an exhibit titled “Following in their footsteps” featuring a “Cretaceous dance floor,” also known as a “Hadrosaur stomping grounds” – consisting of a set of footprints made by hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) discovered by Perot museum paleontologists in Alaska’s Denali National Park.

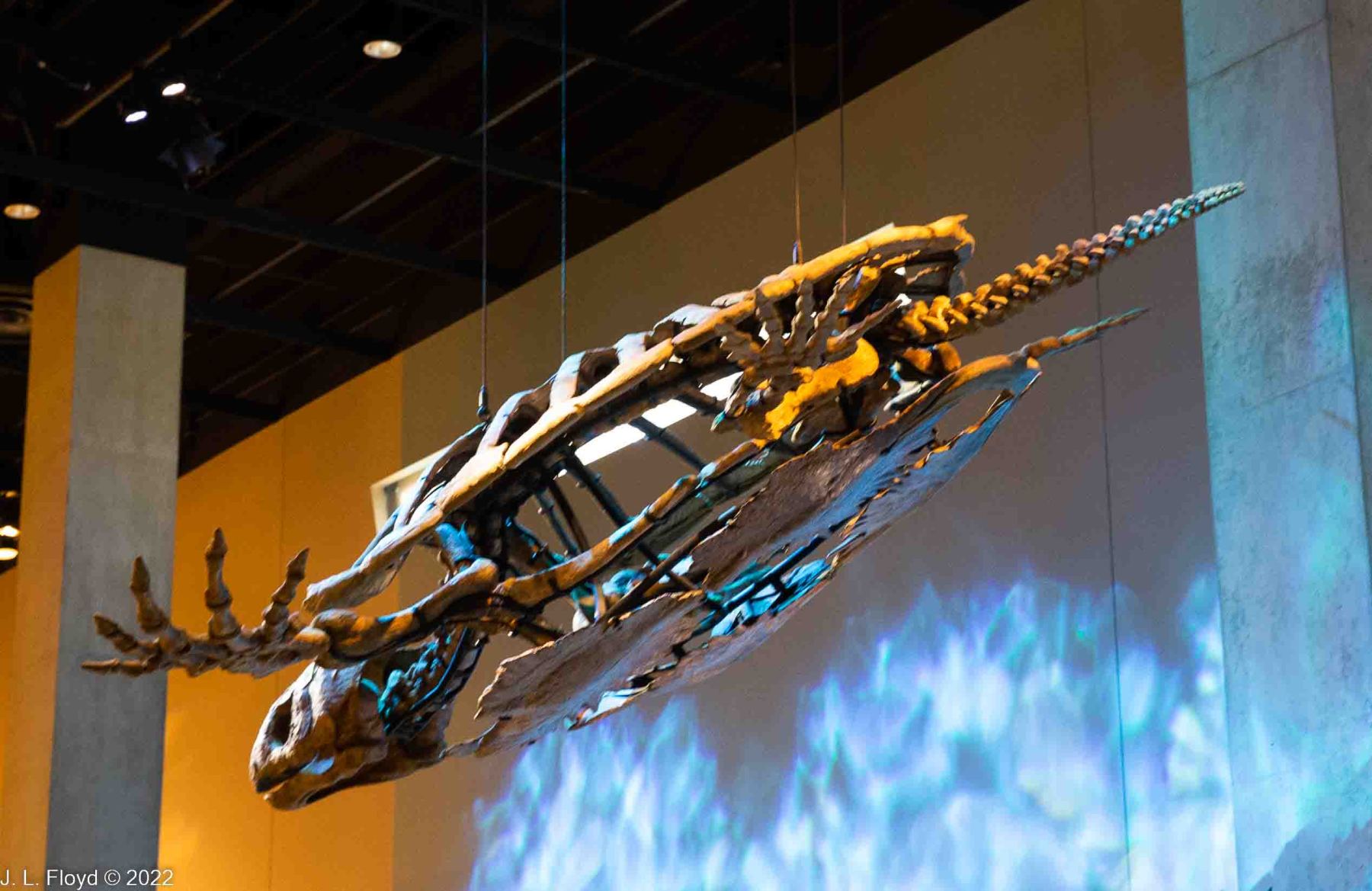

Representation in Pickens Hall is not restricted exclusively to dinosaurs. There was a pterosaur – flying reptile, not related to birds – up in the air above the Alamosaurus, and a prehistoric flying turtle too. (The turtle did not actually fly, even before it went extinct. It was just suspended in the air not far from the Tylosaurus.)

One of the exhibits most interesting to me was devoted to mosasaurs. These were large, predatory marine reptiles closely related to modern monitor lizards and to snakes. They lived in the late Cretaceous period, 90 to 66 million years ago. At that time Dallas was submerged in a tropical sea known as the Western Interior Seaway, which divided North America in half. The exhibit displays a skeleton of a Tylosaurus, one of the larger mosasaurs that lived in the tropical seas of Dallas during the late Cretaceous. This was a fearsome creature, the apex aquatic predator of its time, reaching lengths as great as 50 feet and feasting on all manner of prey including turtles, birds, bony fish, sharks, giant squid, and other mosasaurs.

In one corner of Pickens Hall I encountered the Paleo Lab, where fossils are prepared for research and reconstruction; it is separated from the exhibition room by glass windows, which allow visitors to see inside and watch the preparators work on the fossils.

According to a placard in the Paleo Lab, the smaller dinosaur displayed in the lobby on the first floor of the museum was a Malawisaurus, a smaller cousin of the Alamosaurus, first found in northern Malawi in Africa. It was a titanosaurian sauropod which reached a length of around 36 feet and a weight of 3 tons.

Mounted above the Paleo Lab is the only full-body reconstruction of Nanuqsaurus hoglundi in the world. Nanuqsaurus was another late Cretaceous dinosaur, in this case a carnivore, somewhat similar to T. rex though much smaller. It was discovered in 2014 in the Prince Creek formation of Alaska, and described and named by Anthony Fiorillo, chief curator of the Perot Museum at the time. The “nanuq” part of the name is derived from a word meaning “polar bear” in Inupiaq, a native Alaskan language, and the species name hoglundi honors Forrest Hoglund, a Texas oil executive who has donated generously to the Perot Museum.

Rose Hall of Birds

By climbing a short flight of stairs from the paleontological displays of Pickens Hall, one arrives at an area devoted entirely to birds, which is appropriate since birds are descended from dinosaurs. Exhibits in Rose Hall trace the evolution of birds, who first appeared in the age of dinosaurs, survived the extinction of their non-avian cousins, and continue to flourish today in the so-called age of mammals. Rose Hall also provides an experience whereby you can “create your own bird,” even including its own birdcall, although I did not take advantage of the offer.

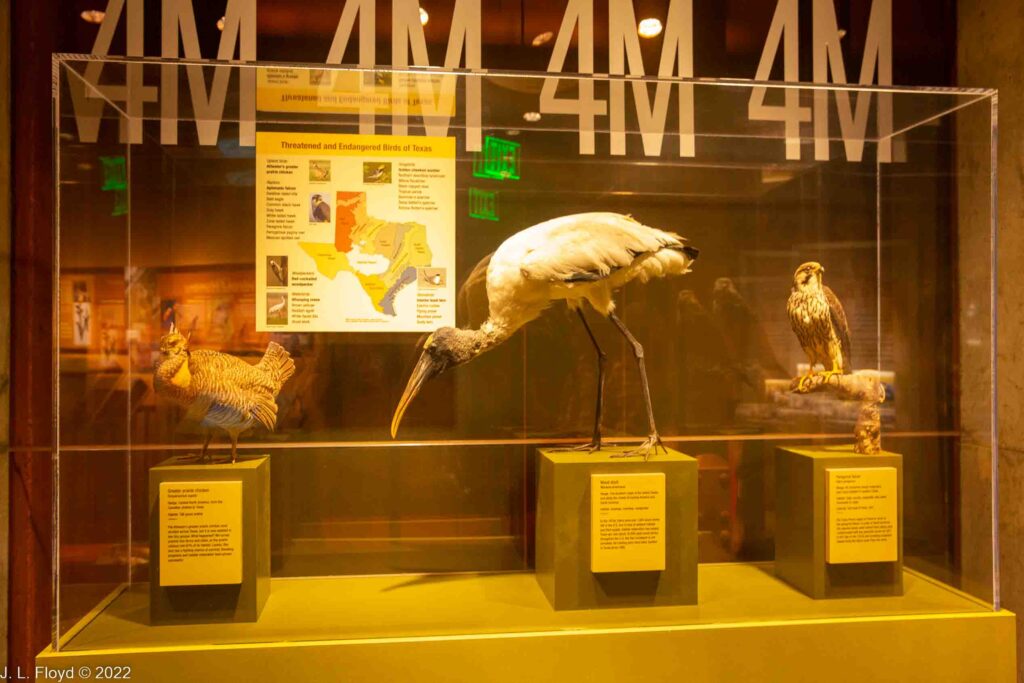

Although the bird exhibits were quite attractive and illuminating, the glass enclosures surrounding them overwhelmed my meager capabilities as a photographer – too many reflections and refractions playing tricks with the light – so I have only one picture to present here. As the placard indicates, it features threatened and endangered birds of Texas.