After completing the cruise on the Guadalquivir during the early afternoon, we were left with some free time to explore as we pleased; many of us chose to visit the Alcázar, which was not on the official itinerary of the tour. For me there was no option – I could not miss the Alcázar. Even more than the Cathedral, for me it is the paramount historical and esthetic attraction of Seville.

I’ve always been a fan of Moorish architecture, but I was unaware until visiting Spain in 2017 that some of the structures I had thought of as Moorish were actually built by Christians (or by Moors working for them) following the Reconquista, though with a strong Moorish influence, in a style known as Mudejar. The Alcázar is an example.

The original Alcázar was indeed built by the Moors, who constructed it as a fortified strongpoint in the tenth century. In the twelfth century a new Moorish dynasty, the Almohads, replaced the previous Almoravid rulers of al-Andalus, moving the capital from Córdoba to Seville; the Alcázar became their main palace, and they greatly expanded it. But in 1248 the forces of Ferdinand III took Seville, and in the aftermath the Castilian kings rebuilt the Alcázar according to their liking; few of the original Islamic-era constructions survived.

The Castilian kings took over the Alcázar as their royal palace, and that is why its name is officially the Real Alcázar (real means “royal” in Spanish; it was not assigned to distinguish it from the fake Alcázar down the street). Although some changes were made under Ferdinand III and his successors, Alfonsos X and XI, it was Pedro (Peter) the Cruel who began the rebuilding of the Alcázar in earnest, in the 1360s.

Peter the Cruel (1334-1369) was an interesting monarch. He seems to have earned his sobriquet of “the Cruel” by a number of murders and executions of his opponents, but he had a number of positive qualities as well; he was a patron of the arts, and he was noted for his support of the commoners, the merchant class, and of the Jews, which earned him the hatred of the Church and the nobility as well as an alternative characterization as El Justiciero, the Executor of Justice. In the end he was overthrown mostly by his own fecklessness, combined with bad luck.

Peter’s father, Alfonso XI, fathered a number of illegitimate children by his mistress, Eleanor de Guzmán, including the twin sons Fabrique and Enrique (Henry of Trastámara). Alfonso XI died of the Black Plague in 1350 and his wife, Queen Maria of Portugal, had Eleanor imprisoned and executed. This of course did not endear either her or Peter to Eleanor’s children, one of whom, Enrique (Henry) de Trastámara), eventually became Peter’s nemesis.

Peter married two women and deserted both in favor of his mistress, Maria de Padilla. His first queen was Blanche of Bourbon, a French princess, whom his half-brother Fadrique (Enrique’s twin) escorted from France for the wedding and was rumored to have slept with her on the way. Hearing the rumors, Peter shunned Blanche, eventually had her imprisoned, and may have had her murdered. He also forsook his second wife, Juana de Castro.

Henry of Trastámara, aided by the King of Aragon and other allies, began a series of rebellions against Peter. In his efforts to retain the throne, Peter committed a series of murders, including some of clergymen, for which he was excommunicated by the Pope. He also reputedly had Henry’s brother Fadrique treacherously murdered. Nevertheless, Henry was at first unsuccessful in his attempts to dethrone Peter. Peter had a good deal of support among the commoners, the merchant class, and especially the Jews, whom he favored. He also received aid from the English.

Eventually, however, Henry prevailed, with the help of his Aragonese allies and French mercenaries. He also took advantage of popular antisemitism to blacken Peter’s image, depicting Peter as “King of the Jews” because he employed a number of them, including one named Samuel ha-Levi as royal treasurer. Peter also tried to curb violence against Spanish Jewry, and had leaders of anti-Jewish pogroms executed.

In 1369 Henry and his allies defeated Peter, and during negotiations afterward Henry assassinated him with the aid of a ruse. As king, Henry of Trastámara proved to be no improvement over Peter, and his reign proved especially catastrophic for Spanish Jews. He enacted harsh laws against them and imposed crippling financial demands on the Jewish communities. In his reign anti-Jewish violence continued to mount, culminating in the great pogrom of 1391, when 4000 Jews were murdered by a mob in Seville, and many more in other cities as well. The Jews had indeed been ardent supporters of Peter, but that was because Henry had harbored animosity toward them from the start. Yet Henry continued to employ Jews as financial advisors and tax collectors.

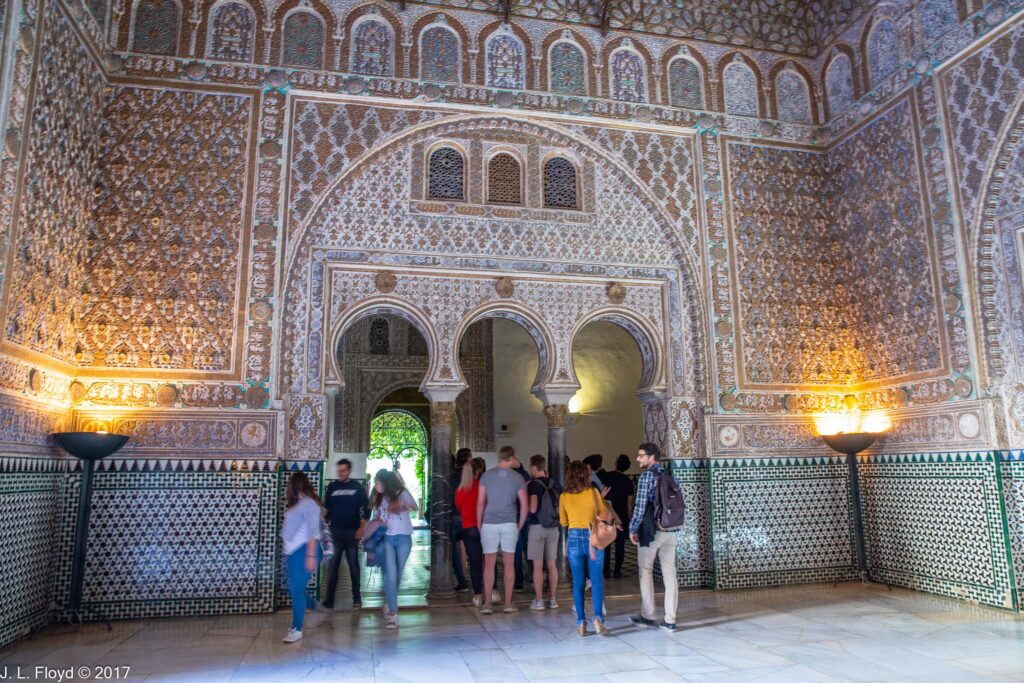

Between 1364 and 1366 Peter had the Alcázar rebuilt in Mudejar style. He was on friendly terms with the Muslim emir of Granada, and imported a number of skilled artisans from there as well as using local talent. Later monarchs made their own additions in other styles – Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, etc.

Visitors enter the Alcázar through the Puerta del León, the Gate of the Lion. This takes its name from a tile plaque inlaid in the stonework above it, which features a crowned lion holding a cross in its claws. Once inside the gate, one finds oneself in the Patio del León, the Courtyard of the Lion. The wall at the end of the Patio del León is one of the few elements of the Alcázar left from Moorish times.

Passing under the arches of the Moorish wall, one enters the Patio de la Monteria, the Courtyard of the Hunt. The entrance to the Palace of Peter the Cruel is at the far end of the patio. The northeast side of the Patio provides entry to the Sala de Justicia, the Hall of Justice; the wing on the southwest contains the is the Cuarto del Almirante (Admiral’s Room) and Casa de Contratación (House of Trade). Originally the palace was only one story high – construction of the upper story began in 1540 and was completed in 1572. But public access is limited to the ground floor only; the upper floor is still the residence of the royal family, when they are in Seville.

I turned off the Patio de la Monteria to explore the right wing of the palace, where the Salón del Almirante is located. It was part of the Casa de Contratación, which the Crown set up in 1503 to control the trade with the Americas. A placard in the Salón notes that the Queen (Isabel) chose Seville as the destination for the trade with the New World because it afforded protection against pirates. This was a wise choice; Cádiz, the obvious alternative, was a prime target for raiders. In April 1587 the English raider Sir Francis Drake occupied Cádiz harbor, destroyed 31 ships and delayed the sailing of the Spanish Armada for a year; in 1596 a combined Anglo-Dutch force occupied Cádiz, destroyed 32 ships and looted the city.

The Salón del Almirante displays several paintings of historical events and personages. The next room, the Sala de Audiencias, or Chapterhouse, was the meeting-place for the officials of the Casa de Contratación; today it is a chapel. It has a stone bench running around the walls where the members sat. It is most remarkable for the altarpiece, which is a triptych painting by Alejo Fernandez, Virgen de los Mareantes (Madonna of the Seafarers), depicting the Virgin Mary sheltering a group of Native Americans with four saints in attendance. The Sala also displays a scale model of a 16th-century caravel.

After the detour through the Casa de Contratación, I skipped back to the Mudejar Palace, where the real treasures awaited. The patios paved with geometric designs and furnished with central fountains were an Islamic tradition that the Christian Castilian kings enthusiastically embraced, and so did I.

Inside the palace, each door and wall was graced with colorful tile framing and borders. The most dazzling room in the palace is the Salón de Ambajadores (Hall of Ambassadors), also known as the Throne Room. It was in fact built as a throne room in the 11th century. King Peter completely remodeled it in the 14th, but continued to use it as a throne room, where he received ambassadors and other dignitaries.

Next to the throne room, in the middle of the palace, is the epitome of Mudejar architecture, the Patio de las Doncellas, Courtyard of the Maidens. The name originates in a legend that the Moors demanded a tribute of 100 virgins a year from the Christian kingdoms. The legend is apocryphal, but what is true is that the courtyard was paved over with black and white marble in the 16th century. It remained in that state until 2005, when it was excavated and restored to its original appearance.

I really needed an entire day to explore and photograph the Alcázar; in fact I had only about three hours, and I missed important parts of the palace, such as the Baths of Maria Padilla, where Peter the Cruel’s mistress enjoyed bathing in private. I devoted an inordinate amount of attention to the gardens, partly because the outdoor light was more conducive to photography – I don’t remember whether flash photography was allowed inside the palace, but in any case I didn’t have a flash attachment with me.

Be that as it may, the gardens of the Alcázar are fabulous, right out of the Arabian Nights. The Moors of course loved gardens, and cultivated them from time immemorial, but the Christian monarchs greatly expanded and reworked them. Today the gardens contain over 20,000 plants of 187 different species.

Immediately in back of the palace are the six Historic Gardens. These were inherited from the Moors but extensively redone during the 16th and 17th centuries. They include the Prince’s Garden, the Flower Garden, the Galley Garden, the Troy Garden, the Dance Garden and the Pond Garden.

The Prince’s Garden is on the southwest side of the palace and has a Renaissance gallery which provides access from the palace and separates it from the Garden of the Flowers. The latter received its present form in the 16th century from Philip II, who loved flowers. Although he was responsible for its Renaissance elements, including the niche with the bust of his father, the Emperor Charles V, he retained the basic Moorish layout of four sectors, planted with citrus trees, and a fountain in the center.

While I was wandering through the Prince’s Garden I stumbled into a beautiful courtyard, the Patio de los Levíes, just outside the Casa de Contratación, with a pool and a charming princess who obligingly posed for a couple of photos. The Patio’s name has to do with the fact that its outside wall was originally part of a house in the Jewish quarter, possibly belonging to King Peter’s treasurer, Samuel ha-Levi.

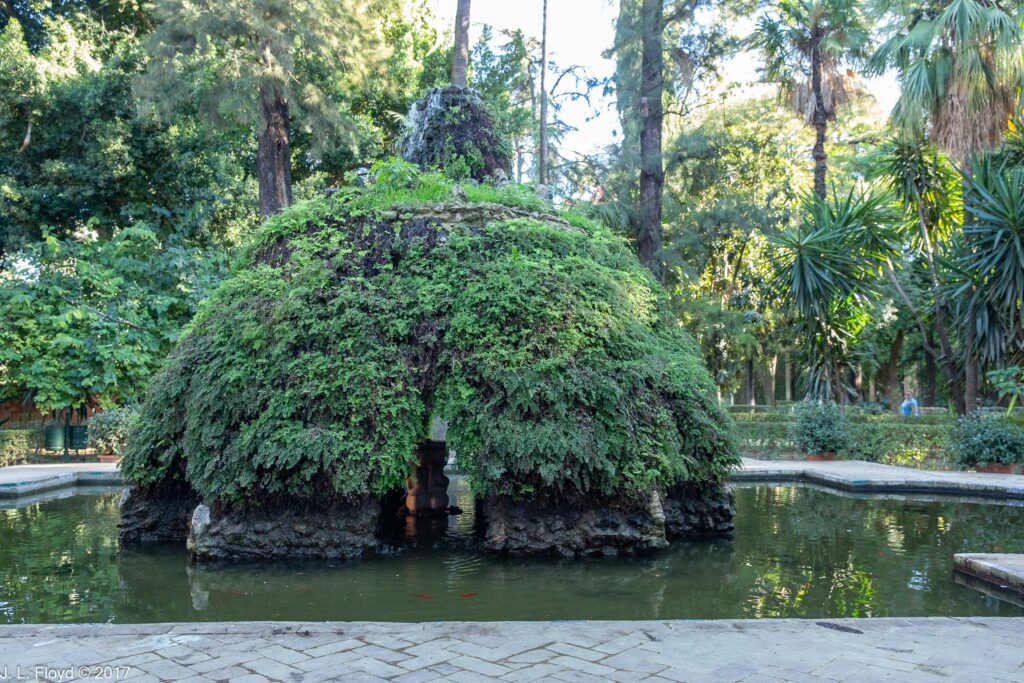

From Philip II’s Flower Garden I wandered out into the terra incognita of the back gardens, where it is easy to get lost. I first encountered the Jardín de la Cruz, the Garden of the Cross. A placard there informed me that it was also known from the sixteenth century onward as the Jardín del Laberinto Viejo, the Garden of the Old Labyrinth, which had been much more extensive – and really was a labyrinth – but in 1910 it had been obliterated, at the insistence of the Queen of Spain, Maria Christina of Austria, wife of King Alfonso XII, who did not like the idea of ladies and gentlemen of the court getting lost in the labyrinth, where all sorts of hanky-panky was possible. Now all that is left of the Old Labyrinth is its central source. This consists of a pool with a mound of greenery in the center, which was intended to represent Mount Parnassus, site of the Oracle of Delphi in Greece.

Next I found myself in the Jardín de las Damas, the Ladies’ Garden, which boasts a wonderful fountain made of Genoese marble, topped with a bronze statue of Neptune by the Spanish sculptor Bartolomé Morel (1504-1579), who also cast the Giraldillo.

From the Fountain of Neptune a walkway leads to a peculiar rose-colored structure with what looks like old-time streetlights on top. I still haven’t been able to identify this item, so I just call it the Mystery Tower.

From the Tower of Mystery the walkway continues to the Pavilion of Charles V. This square structure with a tiled roof seems to have originated in Moorish times, but it was rebuilt for the occasion of the marriage of Emperor Charles V to Princess Isabel of Portugal in 1526. It represents a combination of Mudejar and Renaissance styles.

From the Pavilion of Charles V I wandered off to the English Garden, which appeared to be the wildest and least-manicured sector of the Alcázar gardens. It was established to commemorate the marriage of King Alfonso XIII to Victoria Eugenie Julia Ena of Battenberg, a German princess who was also the youngest granddaughter of Queen Victoria of England. It occurred to me that it would have made a great alternate for the Old Labyrinth as a place for court hanky-panky after Queen Maria Christina’s depredations of 1910.

Eventually, after being lost in the gardens for a while, I managed to stumble back to civilization again, reaching the Galería de los Grutescos, or Grotto Gallery. This actually had been the wall of the Alcázar in the days of the Almohads; in the early 17th century Italian architect Vermondo Resta converted it into an L-shaped gallery, essentially a covered walkway with archways, supported by columns, affording views on both sides. I found that it provides an incomparable overview of the Alcázar gardens.

Resta is credited with introducing the Mannerist style to the Alcázar, in a variant called “grutesco”, in this case involving rocks that project from the wall of the gallery, blending the natural with the artificial – hence the term “Grotto Gallery”. In the wall of the Gallery (not seen in the photo below) is the Fuente de Fama, or Fountain of Fame, which used to play an organ pipe when the water was flowing. Maybe it still does, but I don’t recall it doing so the day I was there. It also formerly had 15 statues of mythological figures, of which six now remain; I haven’t been able to determine what happened to the others.

There is a lane or avenue that runs clear across the gardens from the Fountain of Fame to the opposite wall, and separates the six Historical Gardens from the rest. Looking to the left from above the Fountain, one can see clear across to the Charles V Pavilion. On the left also is the New Labyrinth Garden – that’s not its official name, and I later found out that there is a larger maze garden out beyond the English Garden that I never reached, but the one by the Grotto Gallery is definitely a little maze.

Looking to the right from the same point, one can see several of the Historic Gardens; the nearest and most noteworthy is the Pond Garden, which contains Mercury’s Pool. The pool was originally used as a cistern to collect the water brought in via the old Roman aqueduct and Calle Agua in Barrio Santa Cruz. But other water sources were found in the 16th century, and since then the pool has been merely decorative, and the statue of Mercury, the Roman god of trade – another work of Bartolomé Morel – was added, symbolizing Seville’s status as a prosperous port.

The Dance Garden is also visible in the picture below; it provides entrance to the Maria Padilla baths.

From a vantage point a little farther out, I was able to get a better view of the Little Maze Garden, as I called it. I also spotted a fountain in the guise of a stone lion that spews water from its mouth; this belongs to the Lion Bower, a small pavilion – out of sight in my photo below – with a blue and white tiled roof. Finally there was a pretty gazebo with a fountain in the center.

Closing time was getting near, and it was time to go. On my way out I shot one final picture of a lovely tiled bench with another charming princess sitting on it, feeding a peacock. It was a fitting conclusion to the day.