Seville Cathedral is the fourth largest church in the world, after St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady Aparecida in Brazil, and the Duomo in Milan. It is the third largest cathedral – St. Peter’s is not a cathedral, merely a basilica, because the seat of the Pope as the Bishop of Rome is St. John Lateran. Seville Cathedral is the world’s largest Gothic church – the larger churches are not Gothic in style.

When Ferdinand III took Seville in 1248, he converted what had been the city’s Grand Mosque into a cathedral. The mosque had been completed only fifty years earlier. Its minaret became the cathedral’s bell tower, known as the Giralda.

In 1401 the city fathers of Seville decided to build a grandiose new Gothic cathedral on the site of the former mosque; construction began in 1434 and, when it was completed in 1506, the new cathedral was the largest church in the world, eclipsing Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, which had held that honor for nearly a millenium.

The Giralda was left intact when the cathedral was built, but the builders topped it with a belfry, and, in 1568, erected a sculpture of a pregnant woman bearing arms and a cross atop the belfry. The sculpture’s official title is the Triumph of the Victorious Faith, but it is popularly known as El Giraldillo. It is 3.47 meters tall and is cleverly designed to function as a weather vane. A replica of the Giraldillo stands on the south side of the cathedral in front of the Door of St. Christopher. On the day of our visit, the Giraldo was undergoing maintenance and was partly covered with scaffolding.

We entered the Cathedral via the Puerta del Lagarto, the Door of the Lizard. It is so named because there is a reptile, actually a stuffed crocodile, hanging from the ceiling in front of it. The crocodile was a present from the Sultan of Egypt to King Alfonso X of Castile, successor to Ferdinand III. Why Alfonso had it hung in front of the cathedral door I haven’t been able to determine. But it remained over the door ever after, even when the converted mosque was replaced by the new cathedral in the 15th century.

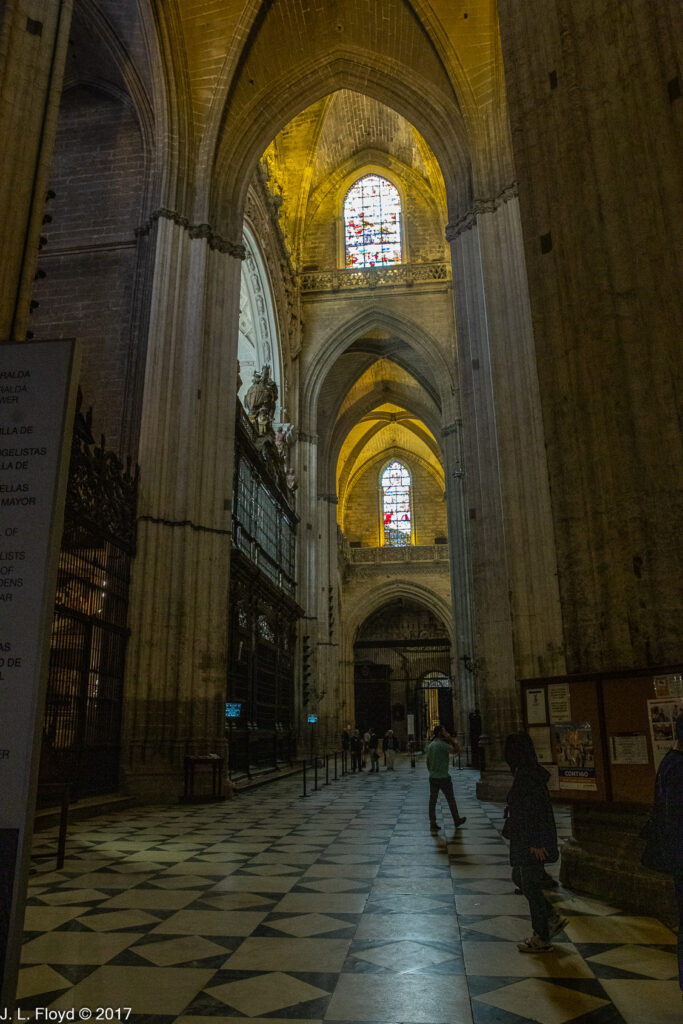

The dimensions of the cathedral are equally as overwhelming from the inside as they are from the outside. The nave is 42 meters (138 feet) high and the total area is 11,500 square meters or 123,785 square feet. There are 80 side chapels, 75 stained-glass windows, and countless paintings.

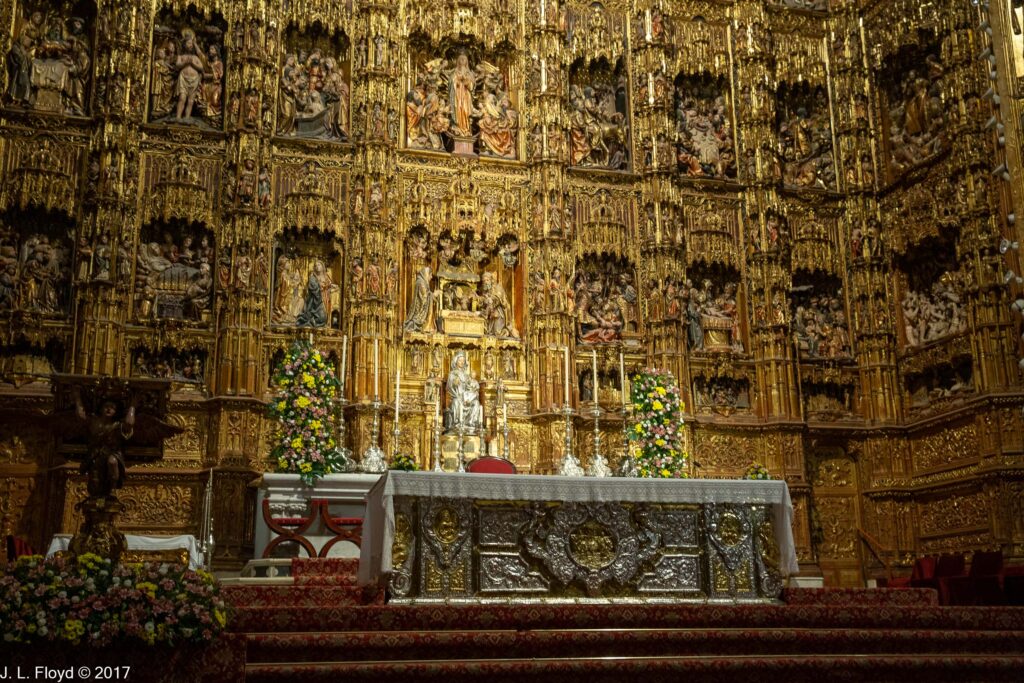

In the middle of the church are located the Choir and the Main Chapel (Capilla Mayor). The latter contains the main altar with its retable (altarpiece), which is carved out of wood and covered with gold. It was the magnum opus of the Flemish sculptor Pierre Dancart, who began it in 1482. He died in 1488, and others continued working on it until it was finished it in 1564. It is 30 meters high by 20 meters wide (98 x 66 feet) and consists of 45 scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary. It is claimed to be the largest and richest altarpiece in the world.

Adjoining the choir, on the opposite side from the Capilla Mayor, is the Antichoir, or Trascoro, containing the ornate stone altar of the Virgen de los Remedios, framed by the tall Gothic vault and its supporting columns. In front of the altar two obscuring white panels had been installed, for what reason I never found out.

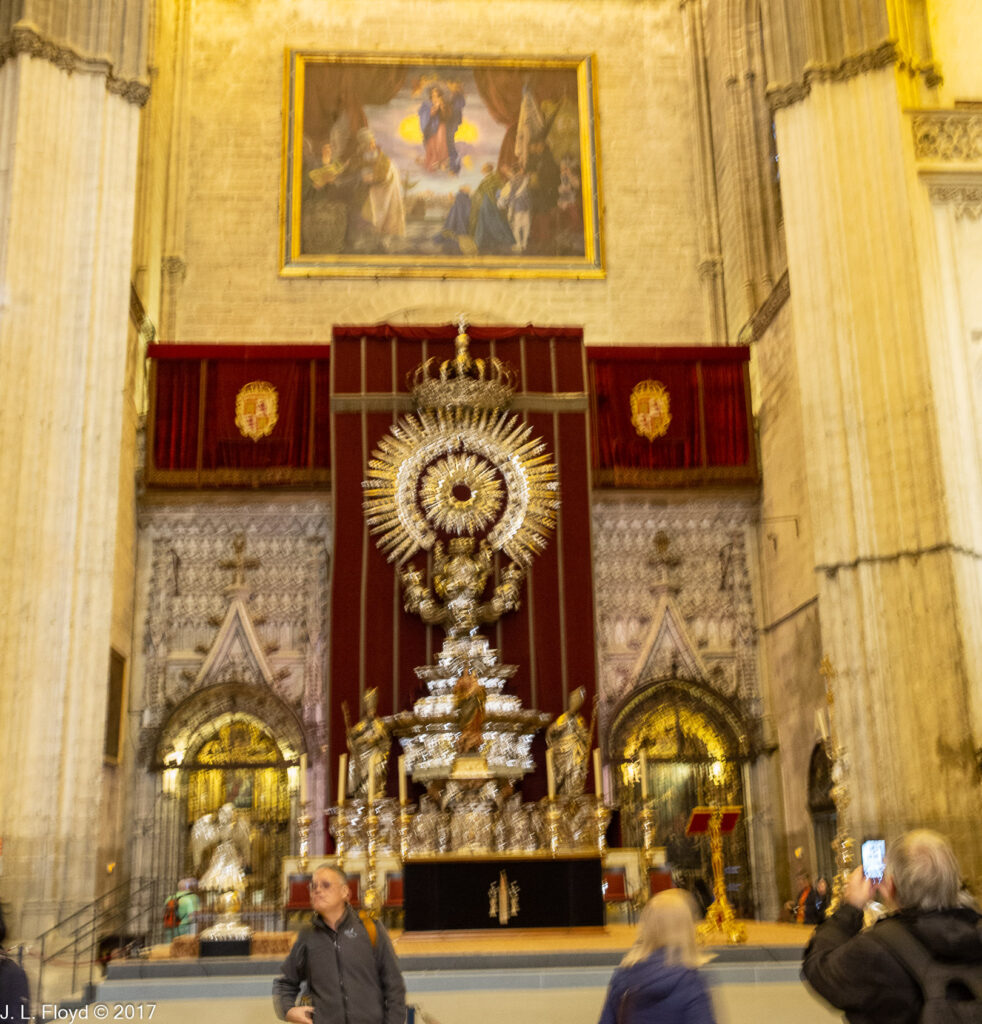

It has been estimated that there are around 40,000 kilograms, or 88,000 pounds, of gold in Seville Cathedral. There is also a rather large amount of silver. A good deal of it, 475 kilograms, is in the Silver Altar. Formally known as the Capilla de la Virgen del Pilar (Chapel of the Virgin of the Pillar), it is located in the north transept and houses a Baroque altarpiece from the end of the 17th century. Behind the altar is a large silver monstrance shaped like the sun. Above the monstrance is a painting depicting the Ascension of the Virgin Mary, and above that is a stained glass window by Arnao of Flanders depicting the entry of Christ into Jerusalem on the upper half and Charity on the lower half.

Chapels, paintings, windows – Many of the other chapels had famous paintings and/or stained glass-windows in them. Unlike the Silver Altar, most were protected by rejas – iron grilles.

The Chapel of St. Anthony is of particular note. It contains a number of paintings, several of which are shown below. On one wall, behind an elegant basin which I speculate is likely a relic of Moorish times, hangs an Adoration of the Magi on the left, and a Circumcision of Jesus on the right. But it is the altarpiece painting for which the chapel is famous: The Vision of Saint Anthony of Padua, a Baroque work from 1656 by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617-1682). It depicts St. Anthony, kneeling with his arms outstretched to a vision of the infant Jesus, who appears in a cloud surrounded by angels and saints. Its fame is not solely due to its artistic worth: it has a turbulent history. In 1813 French invaders looted a number of works of art from the Seville Cathedral, of which The Vision of Saint Anthony was one, but the cathedral chapter persuaded the French commander, Marshal Soult, to accept another painting by Murillo, the Birth of the Virgin, instead. Years later, in 1874, a thief cut out the figure of St. Anthony from the painting. He took the picture to New York, where he tried to sell it to an art dealer. The dealer recognized the clipping and arranged its return to the Spanish embassy, and in 1875 it was expertly restored to the original painting. I haven’t been able to find out what happened to the thief.

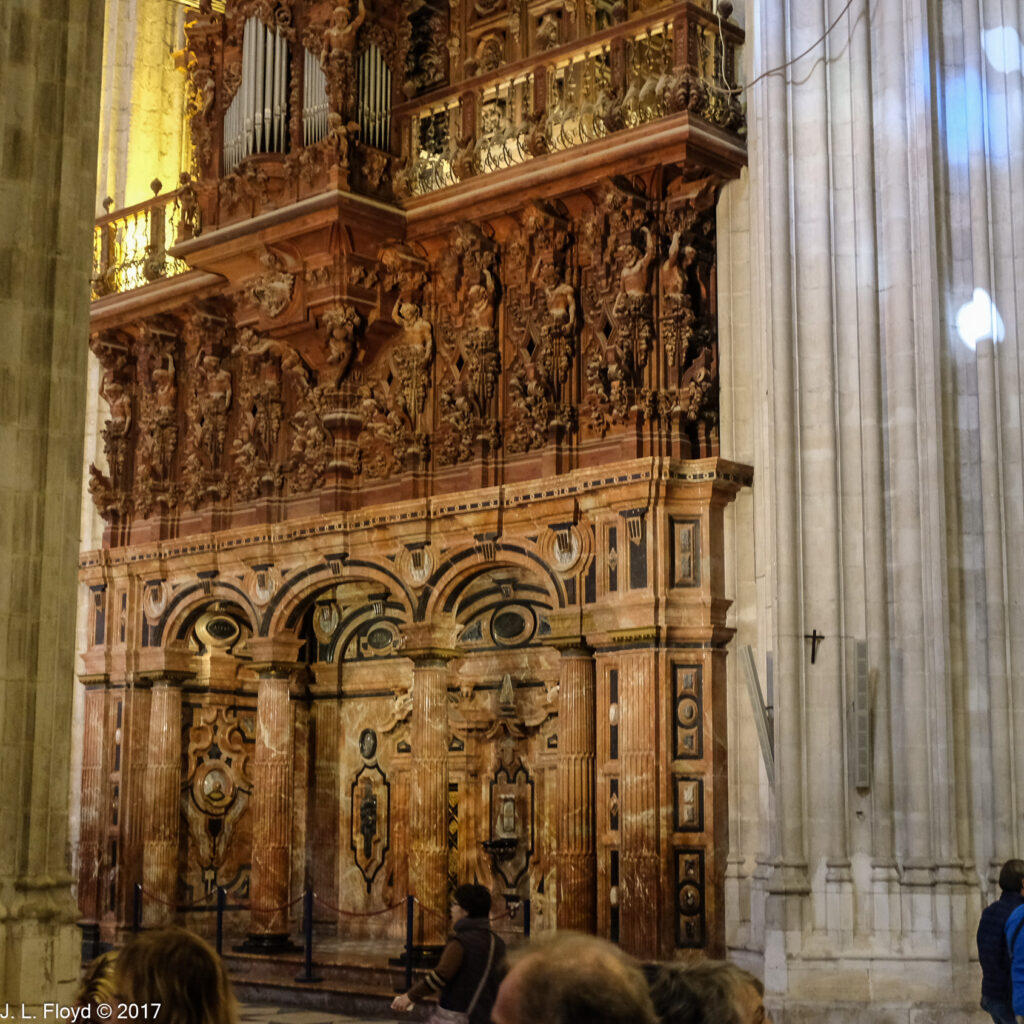

The Cathedral has two organs, each on a lateral wall of the choir. Neither of them are original; they replaced organs which were added to the cathedral in the late eighteenth century but were destroyed in an earthquake in 1888. The current instruments were installed in 1903 and updated in 1996. The organ on the south lateral wall stands on an intricately carved marble porch, and both are topped with elaborate sculptures. They are controlled electronically from a single console.

It is impossible to miss the tomb of Columbus, which stands in the south transept of the cathedral near the Door of St. Christopher. Columbus’ son Diego is also buried in the Cathedral.

Columbus, who died in 1506 in Valladolid, Spain, was originally buried in a convent there, but his remains were later removed to Santo Domingo, on the island of Hispaniola, and then to Cuba. The tomb which now stands in Seville Cathedral was originally built in 1892 for the Cathedral of Havana, Cuba, but when Spain lost Cuba in the Spanish-American War of 1898, it was brought to Seville and installed in the Cathedral. The elaborate catafalque, which contains Columbus’ remains, is borne by the kings of Leon, Castile, Aragon and Navarre. These are of course idealized kings and not historical figures.

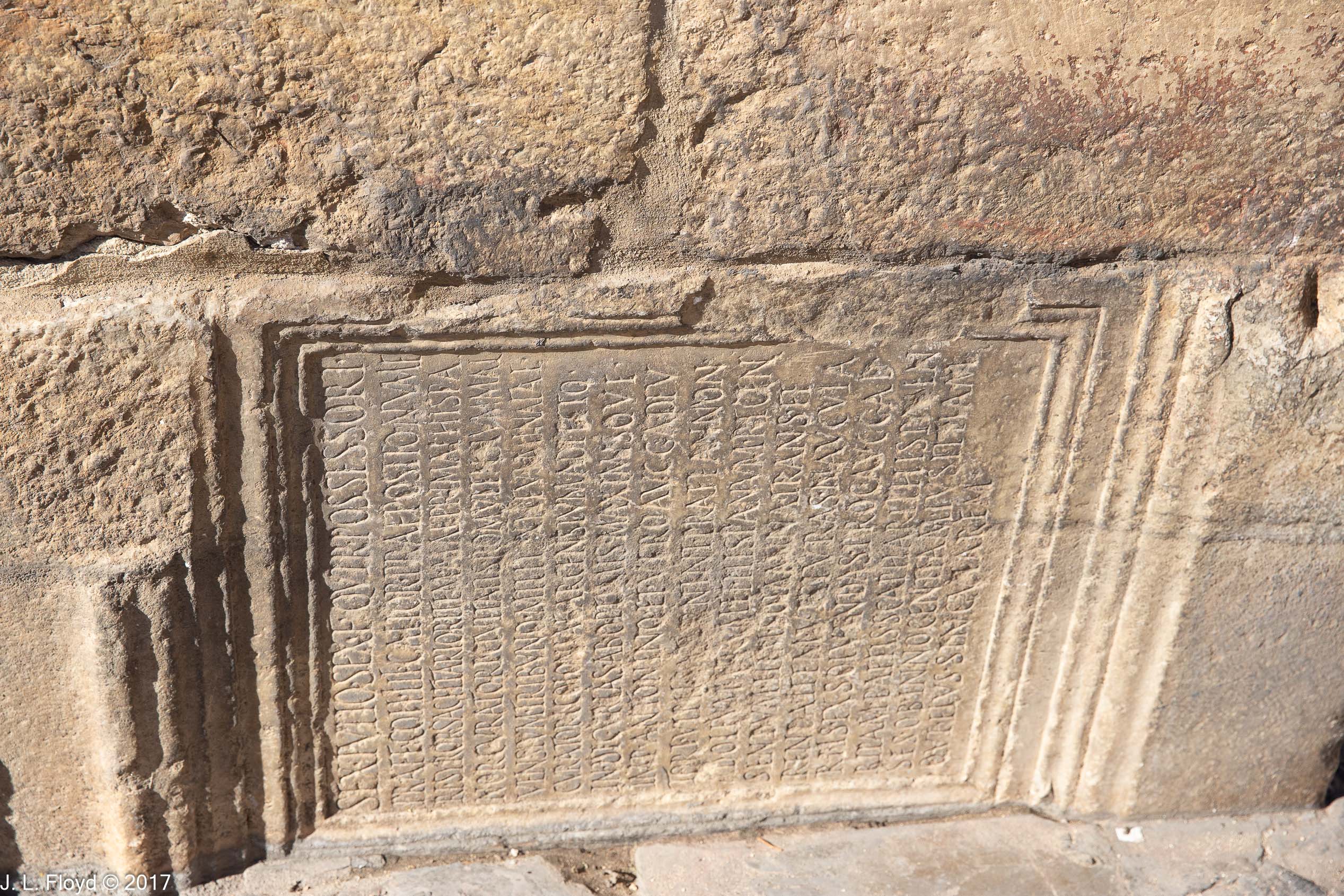

In addition to Columbus, a number of other eminent personages are buried in the Cathedral, including several kings of Castile and their wives (King Ferdinand III, conqueror of Seville; his successor Alfonso X, the Wise, and his wife; Pedro the Cruel). A number of lesser figures – cardinals, archbishops, etc. – are also commemorated there, such as the Bishop of Scalas, who died in Rome and is buried there, but has a cenotaph in Seville Cathedral, photographed by Sandie.

Near the tomb of Columbus I encountered an unfamiliar piece candelabra-like object which resembled a Hebrew menorah but has figures of saints instead of candlesticks; I haven’t been able yet to determine what it is called. In the Sacristy we found, as one might expect, a number of relics and religious objets-d’art.

The Cathedral employs a myriad of people to perform housekeeping and maintenance, and I encountered a worker who was producing some entertaining fireworks while evidently cleaning up one of the huge columns supporting the nave.

We exited from the cathedral via the Patio de los Naranjas, the Courtyard of Oranges. Along with the Giralda, this is one of the few elements surviving from the old Muslim mosque. It was the area where the worshipers performed their ablutions before entering the prayer hall. It is a garden spot, full of orange trees, and the builders of the Cathedral did well to preserve it.

From the Patio we exited to the Calle Alemanes (German Street) through the Puerta del Perdón, the Door of Forgiveness. It is also a holdover from the old mosque, as indicated by its horseshoe shape. Therefore, regardless of whether one is Christian or Muslim, all sins are forgiven when one passes through this door. 😉