One reason I wanted to go to Japan in April was to see the cherry blossoms, and according to Dave Winter, Oeno Park was a good place to do that. So Oeno Park was the first place I headed for, and I was not disappointed.

Prior to 1868 the grounds of the present-day park belonged to Kaneiji Temple, one of the largest and richest temples in Japan. The temple was destroyed in the civil war following the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and then converted to a public park, one of the first opened in Japan.

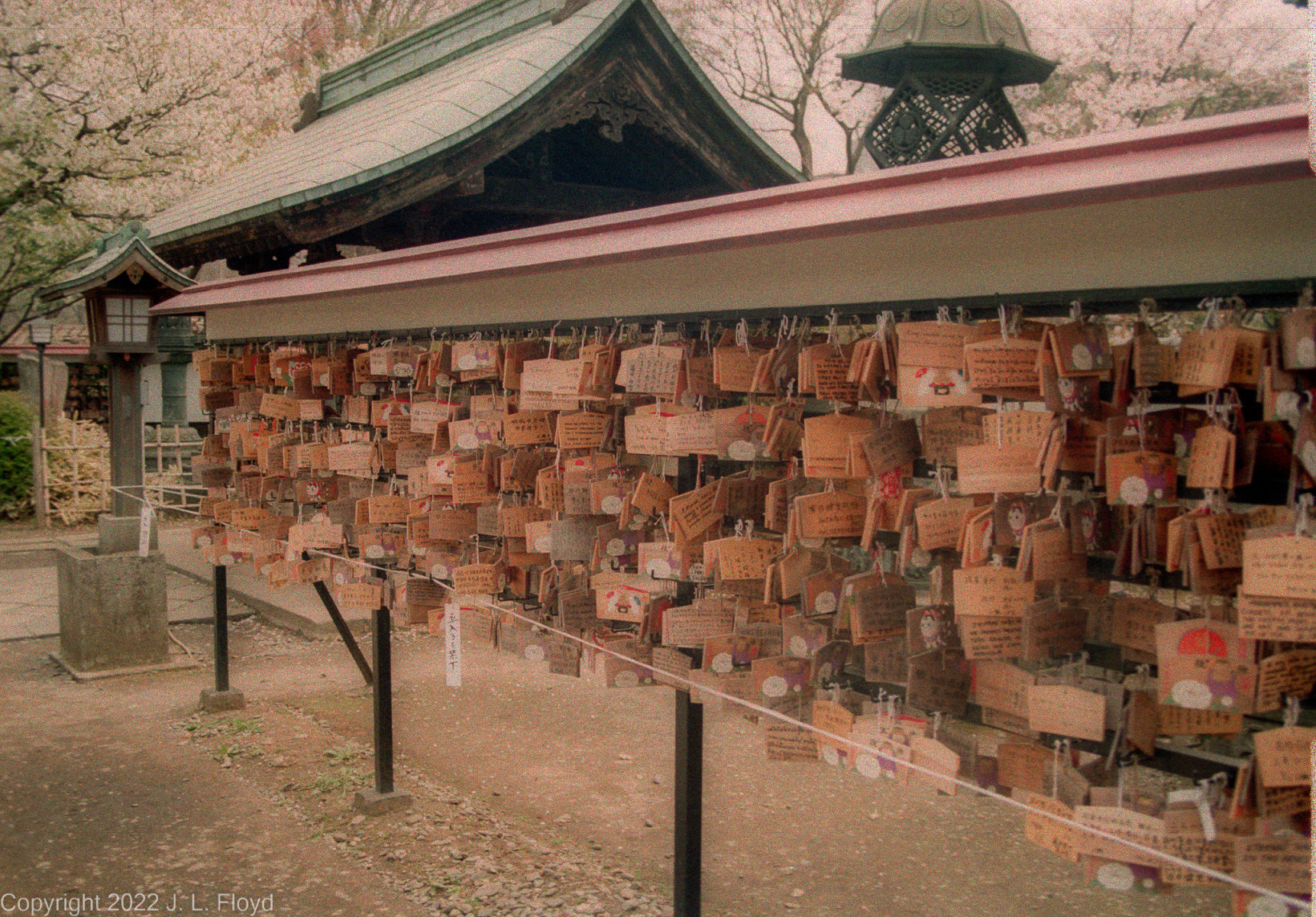

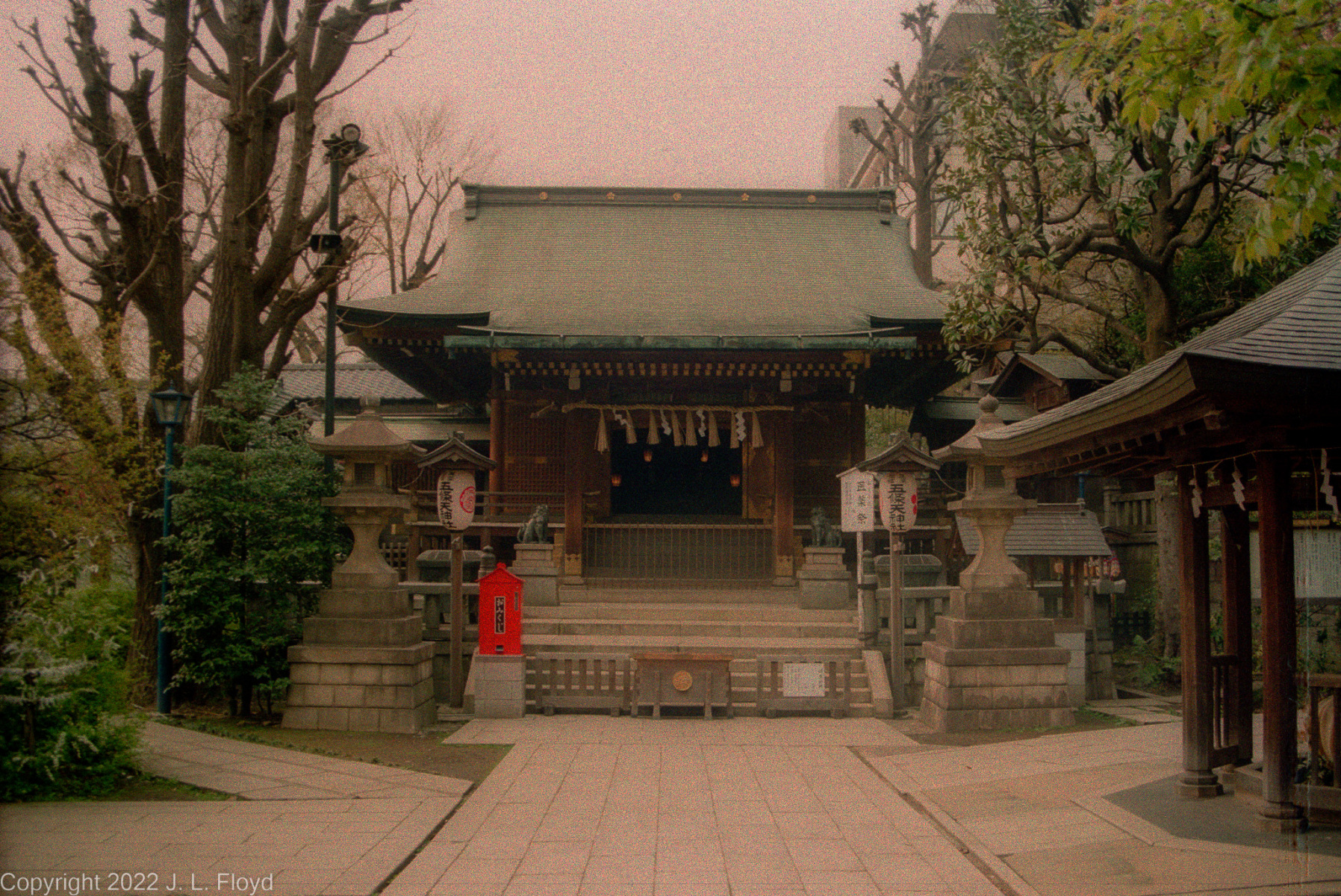

Today the park is one of the city’s most popular spots for viewing the cherry blossoms in the spring. It also contains a myriad of other attractions – several museums, temples, shrines and Japan’s first zoo.

My starting point for exploring Ueno Park was Shinobazuno Pond, a small lake on the west side of the park where one can rent boats and row around the lake in leisurely fashion. It’s a very relaxed setting amidst the hustle and bustle of a giant metropolis, with cherry trees lining the shore and a small temple on an island in the middle.

Skirting the pond, I moved on through the park’s lanes and byways, which were dense with crowds of people strolling and picnicking under the cherry trees.

Ueno Park is the site of a number of temples and shrines, the most famous of which is the Toshogu Shrine, built in the 17th century by the successors of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, and dedicated to his memory. In those days the shogun was the de facto ruler of Japan, and the Emperor was only a figurehead. Tokugawa Ieyasu was the model for the daimyo (warlord) Toranaga in James Clavell’s best-selling novel Shogun, and although the plot of the novel is preposterous, it is based to some extent on historical facts. For example, there actually was an English pilot who arrived in Japan on a Dutch ship and became an advisor to Ieyasu. His name was William Adams, not John Blackthorne, and he did not play the pivotal role in the events leading up to the climactic battle of Sekigihara assigned by Clavell to Blackthorne. Nor was he the illicit lover of a noble Japanese lady; there was indeed a Christian wife of a daimyo vassal of Ieyasu who was kidnaped and held hostage by their enemies, but her Christian name was Gracia, not Maria, and she was not Adams’ lover, nor was she the daughter of the traitor Akechi Jinsai. I don’t know why Clavell changed the names of so many of the characters in the book; the dictator Goroda’s real name was Oda Nobunaga, and he really was assassinated by a vassal who turned traitor and was then himself killed (Akechi Mitsuhide); and the man who first succeeded to his mantle, the Taiko Nakamura, was actually the formidable Hideyoshi Toyotomi, who really did invade Korea in the 1590s. Perhaps Clavell renamed Tokugawa Ieyasu to Toranaga Yoshi because “Yoshi” it is easier to pronounce than “Ieyasu,” but this isn’t true of the other names. One of the names not changed was Toranaga’s nemesis Ishido, or Ishida, who was defeated at Sekigahara, but not executed in the manner described by Clavell; that punishment was indeed inflicted, but on someone else, and not by Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Nevertheless, the real Tokugawa Ieyasu did become shogun, founding a dynasty that lasted for two and a half centuries. He did not have a ninja blow up Adams’ ship to placate the Portuguese. That ship, which was originally named the Erasmus, but renamed to the Liefde before it sailed to Japan, made landfall in Kyushu, not on Izu Peninsula in Honshu. It was later sailed to Edo, but by then was rotten and sank soon after arrival. Although Ieyasu did not allow Adams to leave Japan until 1613, he employed him in ship construction projects and made him his official interpreter, replacing a Jesuit priest in that capacity. When Adams finally did obtain permission to return to England, he turned down the opportunity, though he went on several commercial expeditions to Southeast Asia. Probably Adams remained in Japan because he liked it there; he lived a far better life at the shogun’s court than he could ever have aspired to at home. He died in Nagasaki in 1620.

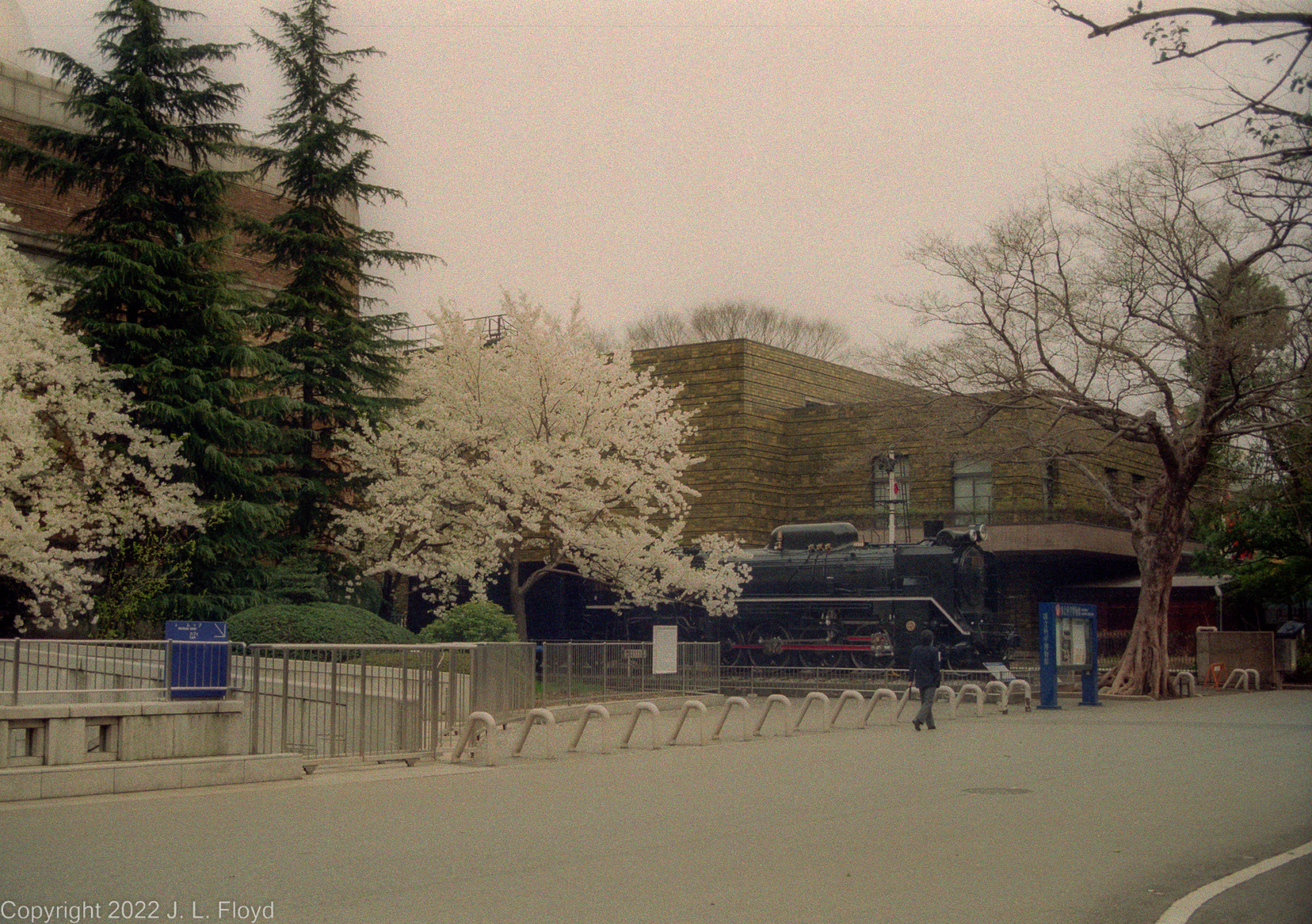

Ueno Park is home to several outstanding museums, and I would have liked to visit all of them, but I had time for only one, the Tokyo National Museum, which contains a number of historical and archaeological exhibits that I particularly wanted to see. I was tempted to visit the National Museum of Science and Industry, but time constraints forced me to settle for photographing the two major exhibits located just outside the museum, the Blue Whale and Steam Locomotive D51.231.

The Tokyo National Museum is a vast place, and I would have needed several days to see it all, let alone the other museums in the park. By closing time I was exhausted and ready to head back to Dave’s place for dinner. Fortunately Ueno Station was close by and it was a short walk to board the metro for the trip back.