On December 4, 2002 our tour group piled into two buses and set out for the eclipse viewing site, which was in the Outback, a six-hour bus ride from Arkaroola. The site was near Mt. Hopeless, which was appropriately named because there was obviously no hope of ever getting back to civilization, or even surviving, if you were stranded out there without motor transport. Quite simply, it was in the middle of nowhere.

It’s often said that getting there is half the fun. This is true, if you define “getting there” as traversing mile after mile of desolate, featureless landscape, then stopping halfway for lunch and finding out that one of the buses has a hole in the radiator and all its coolant has leaked out, so that it can neither go on nor go back, because there is no water the rest of the way, and you can’t risk having the other bus break down and leave everyone stranded in the middle of nowhere, so it looks like everyone will have to pile onto one bus, where the passengers will take turns standing up and sitting down while it wends its way back to Arkaroola, hoping that it doesn’t break down too.

Fortunately, that didn’t happen. We had a few bad moments while Rob Hill and the bus drivers discussed the situation. But they had a backup plan, and soon a Toyota truck showed up with a large tank of water in the bed. It followed us the rest of the way to the viewing site and back to Arkaroola, and whenever the bus radiator ran short of water, we stopped while it was refilled from the truck. I don’t know where the water truck came from nor whether this had been long planned for beforehand, but I have to hand it to Rob Hill and the bus operators for covering this contingency, because it saved the trip.

Finally we arrived at the viewing site. It was the most godforsaken place I’ve ever seen. It was completely flat for miles around. The landscape was absolutely featureless. There was nothing there – no gas station, no souvenir shop, no hot-dog stand, no toilets, no trees, not even a billboard or a beer can – nothing. It was absolutely perfect for our purposes, except maybe for one issue: the wind. I set up my camera on a tripod and the wind blew it over. But it was undamaged, and after righting the tripod I photographed the eclipse without further hindrance, except from my own ineptitude.

I had been advised not to try to photograph my first eclipse, because you risk becoming so involved in operating your equipment that you miss seeing the eclipse. I completely disregarded that advice. I had an Olympus OM-1 film camera and used a 70mm TeleVue Pronto scope for a lens, with a mylar filter over the aperture. I had the setup mounted on a TeleVue Telepod, which is just a plain tripod, suitable for holding a TeleVue scope but not equipped with any tracking or guiding capability. I had Ektachrome 200 and 400 color film, and some Fujifilm – I don’t remember what I actually wound up using.

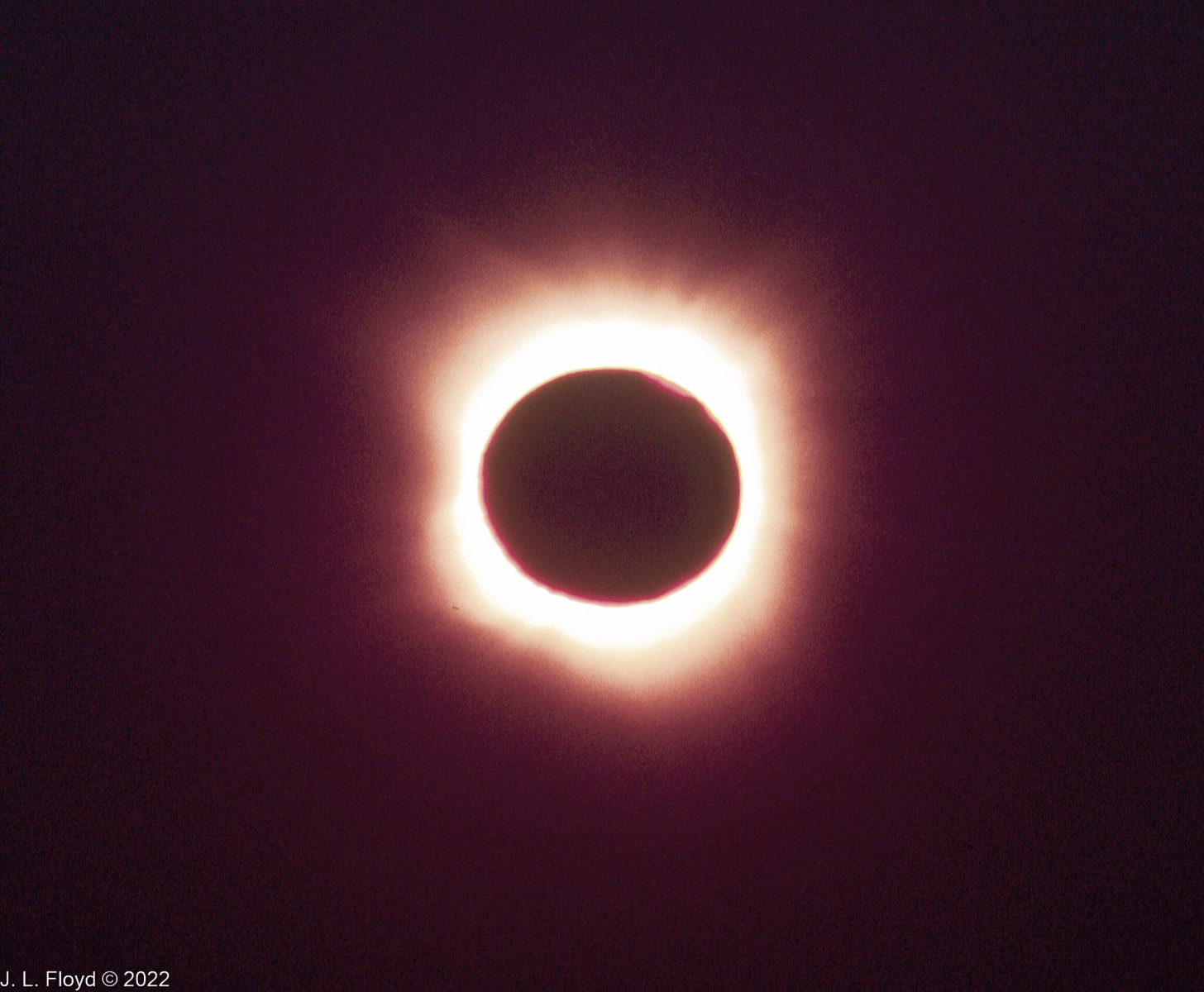

Although completely inexperienced as a solar eclipse photographer, and hardly an expert at photography in general, I managed to capture a respectable sequence of images. I was a little slow in finding the right combination of optics. The solar image didn’t fill the scope’s field of view as much as I would prefer, so I tried using eyepiece projection to magnify it, but that made it too large, so after a couple of shots I switched back to the unmagnified setup. I also fumbled around for a while trying to nail down the appropriate exposure settings, and missed shooting first contact (the second when the Moon’s shadow first reaches the Sun’s disk) as a result.

We were seeing the eclipse almost at the very end of its path across the Earth. It began over the South Atlantic, continued over Africa and the Indian Ocean, and finished up in Australia, a bit to the northeast of our site. The maximum duration of totality was 2 minutes, 4 seconds, but that was in the middle of the Indian Ocean. At our viewing site totality occurred about 7:45 PM and lasted about 30 seconds. The partial phase began about 6:40 PM. Shortly after the end of totality, the sun set, still partially eclipsed.

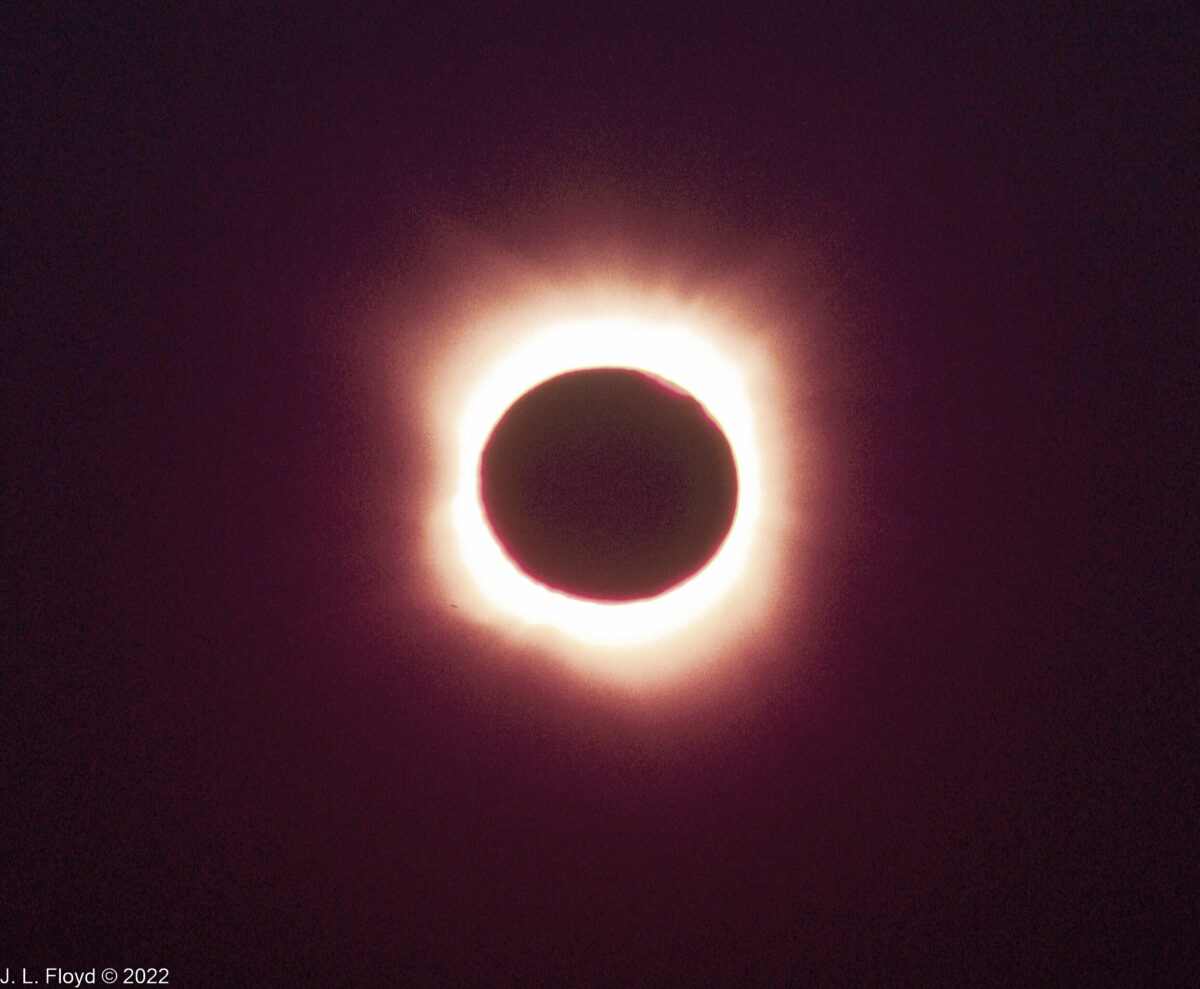

Photographing totality is tricky. Until it arrives, you have to keep the filter on your scope; if you look at the unfiltered sun, even when partially eclipsed, you will blind yourself and destroy your equipment. But when totality arrives, it instantly becomes dark, and you have to jettison the filter quickly – otherwise you’ll get no picture at all. You also have to speedily readjust your camera settings to compensate for the change in light levels. Especially with as short a duration of totality as we had in 2002, if you fumbled around trying to find the right settings for long you would miss totality entirely! Fortunately I managed to avoid this pitfall and captured some decent images of the totally eclipsed sun.

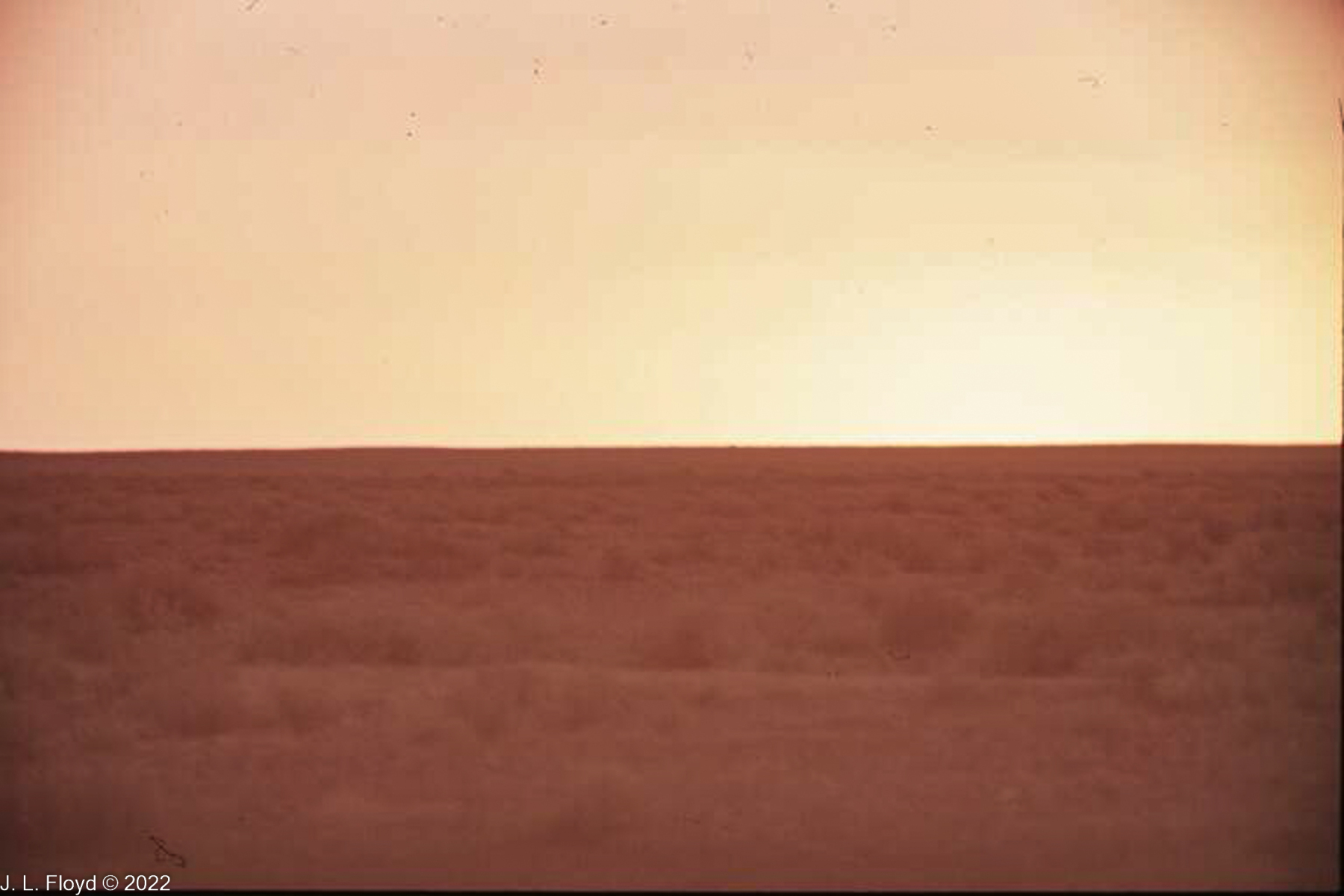

Normally the post-totality phase of a solar eclipse is something of an anticlimax, and many people ignore it altogether, packing up and going home right after the Sun begins to emerge from the Moon’s shadow. That wasn’t the case for the 2002 eclipse in Australia. The sight of the partially eclipsed setting on the horizon was spectacular and kept people mesmerized until the last tip of the crescent disappeared off the edge of the world.

The organizers had planned carefully, and they had brought along equipment to provide a superb barbecue using organic beef contributed by local ranchers. Once dinner was over, we climbed into the buses and began the six-hour drive back to Arkaroola, which most of us spent in an unconscious state. Arriving back at our lodgings in the middle of the night, we were able to get just a few hours more sleep before we had to rise and pack for an early-morning departure for Adelaide.