After seeing the Habsburg Winter Palace, the Hofburg, in the morning of June 19, in the afternoon I went to see their Summer Palace, Schönbrunn. It is located well to the west of the city center, in an area which was rural at the time of its inception. It began as a hunting lodge for the Habsburgs; it was only in the time of Empress Maria Theresa, the 1740s and 1750s, that Schönbrunn became a major palace, and since it was she that was mainly responsible for its construction, it’s appropriate to say a few words about her at this point.

Maria Theresa became Empress only because of a combination of unusual circumstances. Maria Theresa’s father, Emperor Charles VI, inherited the throne from his elder brother, Joseph I (r. 1705-1711). In 1703, Charles had signed an agreement called the Mutual Pact of Succession, which provided that in the absence of male heirs, Joseph’s daughters should have precedence over Charles’ in the succession to the throne. As it turned out, neither Joseph nor Charles had sons, and after Joseph died in 1711, his daughter was first in line for the throne. However, there was another obstacle: the Salic law inherited from the early medieval period precluded female inheritance. Though the Salic law no longer was considered sacrosanct, it ensured that any male Habsburg relatives who were around would contest the succession. Charles VI attempted to deal with both of these considerations by issuing the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, which proclaimed that his daughters, should he have any (none had been born yet), would have precedence over Joseph’s in the succession. As it turned out, Charles had three daughters but no sons, so Maria Theresa, as eldest daughter, born in 1717, inherited the throne.

Issuing an edict was one thing, getting all the interested parties, both foreign and domestic, to abide by it was another. Charles spent the rest of his life trying to get all of them to sign on, and in doing so he made concessions that seriously weakened the Austrian monarchy. Worse yet, when he died in 1740, most of the major foreign signatories – France, Spain, Prussia, Saxony and Bavaria – repudiated the Pragmatic Sanction. (Why should they uphold it, when Charles himself had renounced the Mutual Pact of Succession?) The result was the War of Austrian Succession (1740-48), which began when the Prussian king, Frederick II, invaded and annexed the rich Austrian province of Silesia. Then France invaded from the west and occupied Prague.

Maria Theresa had married Franz Stephan, Duke of Lorraine, in 1736, by virtue of which he had become de jure Holy Roman Emperor Franz I, and it was expected that he would become the de facto ruler as well. However, Maria Theresa defied these expectations and clung to power for the rest of her life; after Franz I died in 1765, and their son Joseph II became co-ruler with his mother, she continued to hold the reins of government until her death in 1780. She rallied the Austrian armies, instituted important reforms, and held her enemies at bay. Then, in 1756, she made an alliance with her former enemy France as well as the Russian Empire. In the Seven Years’ War which followed, she nearly succeeded in overthrowing Frederick the Great, who was on the verge of total defeat when the sudden death of Empress Elizabeth of Russia, and the subsequent accession of the Prussophile Tsar Peter III, led to the withdrawal of the Russians from the anti-Prussian coalition just as the Cossacks were entering the outskirts of Berlin. In the end, Maria Theresa kept her domains mostly intact, though she never regained Silesia from Frederick the Great.

Maria Theresa had received the Schönbrunn estate as a wedding present, and upon her accession to the throne she entrusted her personal architect, Nicholaus Pacassi, with the transformation of the hunting lodge into a real palace. During the remainder of her reign the palace acquired the extent and form it has today, although its external appearance would later undergo significant changes.

Sandie, who was exhausted after the morning’s trek in Vienna, wasn’t up to going to Schönbrunn and stayed on the boat. Thinking that there would be no occasion for long-distance shots in the palace, and knowing that photography was not allowed there anyway, I decided not to take my 70-200 mm telephoto lens with me, much to my later regret.

Arriving by bus in front of the main gate, flanked by two towers topped with Habsburg eagles, I was initially struck by the seemingly vast expanse of bare space in front of the palace itself, which took a while to cross. It turned out that this was a tiny fraction of the huge extent of the palace grounds. It is covered mostly with white stone and is called the “Ehrenhof,” translated either as “Court of Honor” or more loosely as “Parade Ground.” To the right as one crosses the court is a pool with a sculptured fountain. There are supposed to be two of these in the courtyard, called the Ehrenhofbrunnen, one in the east basin and one in the west, but I saw only the one in the west basin; its three main figures represent the major rivers of the area, the Danube, Ems and Inn. The fountain in the east basin supposedly features an allegorical representation of the Habsburg provinces of Galicia, Lodomeria and Transylvania, but I only saw an empty basin – perhaps the statues had been removed for refurbishing. (Note: Lodomeria is a Latinized form of “Volodymyr.” The name refers to a piece of Poland which Austria acquired along with Galicia in the First Partition of Poland in 1772. Transylvania was already a Habsburg dominion because it was part of the Kingdom of Hungary.)

Photography is not allowed inside Sch

My pretty little Sch

Upon finishing the tour of the palace interior, we had some free time to frolic in the gardens before meeting the bus for the return trip. Unfortunately the palace grounds are far too vast, and I was already too tired from all the trekking I had done that day, to see all but the attractions closest to the palace. Among the most accessible was the area right in back of the palace, known as the Grand Parterre, which is a large expanse of open space filled with grass, flowerbeds and walkways and bordered with tall hedges. Lining the walkways by the hedges are sculptures of figures mostly from classical antiquity. At the end of the Parterre is the fabulous Neptune Fountain, commissioned by Maria Theresa in the last years of her life and completed just before her death. It depicts the sea-god Neptune standing atop a rocky grotto in a shell-shaped chariot holding a trident, and surrounded by his entourage of demigods, nymphs and Tritons. Unfortunately, I did not get close enough to it to get a good picture, and I had left my telephoto lens behind. However, you can see a marvelous picture of the fountain here.

Beyond the Neptune fountain there is a hill, 60 meters (200 feet) high, on top of which stands a gloriette. A gloriette is a building in a garden situated on a site that is elevated relative to its surroundings. The largest known such structure is the one on the hill at Sch

The Gloriette served as an observation platform, dining hall and festival pavilion. It was furnished with decorative sculptures by the Salzburg master Johann Baptist von Hagenauer. Emperor Franz Joseph liked to take his breakfasts in the Gloriette. The Gloriette was destroyed in World War II, but afterward rebuilt, and the dining room was converted into a caf

After Maria Theresa’s death in 1780 the palace fell into disuse until the early nineteenth century, when Franz I again began to use it as a summer residence. Napoleon made it his headquarters in his invasions of 1805 and 1809 and occupied the quarters formerly used by Maria Theresa’s husband Franz Stephan. Afterward the bedroom he slept in became known as the Napoleon Room.

In 1810, following the French victory over Austria at the Battle of Wagram, Napoleon coerced Emperor Franz I into an alliance, to be sealed by marriage to Franz I’s daughter Marie Louise. Napoleon and Marie Louise had a son, Napoléon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte, After Napoleon’s defeat and abdication, Marie Louise, returned to Vienna with her son and resided at Sch

At the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Sch

Franz Joseph was born in the Sch

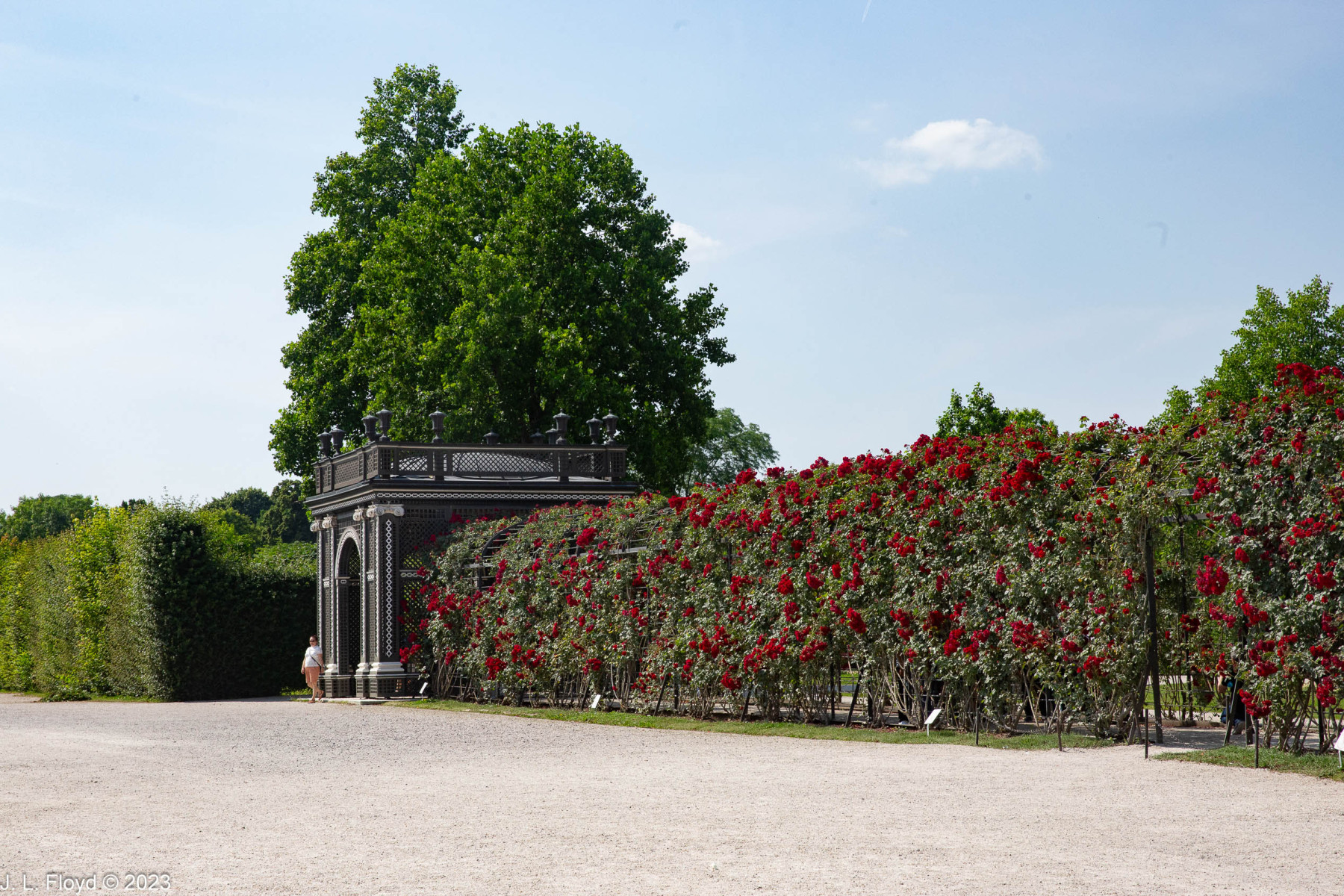

One of my favorite features of Sch

To the west of the Grand Parterre, among other attractions, is the Tiergarten, which claims to be the world’s oldest extant zoo. It was founded in 1752 by Maria Theresa’s husband, Franz Stephan. Out at the west end of the palace grounds is the Palmenhaus, a great greenhouse filled with exotic plants; the W

During the ride back to the Monarch Queen I attempted, mostly unsuccessfully, to shoot a few scenes from the bus. Nevertheless I have included a few of the pictures here to show some scenes of the outlying districts of Vienna.

This bus ride impressed upon me the extent of the graffiti problem in Vienna, which our guide had acknowledged earlier. The graffiti are far more profuse, and more visible, in the outlying districts than in the center, where I had never noticed any. It was a bit of a surprise to me because I had always thought of graffiti as mostly an American and southern European issue, not something shared by the disciplined and orderly Germanic peoples. But then the Austrians have always been considered by their northern brethren to be the least disciplined and most rowdy of the Teutonic tribes. (Now tell me that the graffiti craze has taken hold in Berlin, too….)

On the way back to the Monarch Queen we also passed the Wien Westbahnhof, or Vienna West Station, which for years was the main railway station of Vienna, until the advent of the new Wien Hauptbahnhof (Vienna Central Station) in 2015. Now the Westbahnhof is mainly a commuter station, though it also serves an intercity rail service from Salzburg. At the time I thought that the Westbahnhof was the striking building shown in the pictures here, but subsequently I discovered that it is actually associated with the BahnhofCity project, a development completed in 2011, and that it is an office building and shopping center; the railway station is hidden behind it in my pictures. Also not seen is an establishment called MotelOne, a colossal hotel flanking the other side of the Westbahnhof. Regardless, the BahnhofCity building with its unsupported upper-story corner section is one of the most unusual structures I encountered and well worth a picture. A better picture of the BahnhofCity complex on Europaplatz can be found on the Westbahnhof web page.

Back on the ship, I retrieved my 70-200 telephoto lens and used the remaining daylight hours to shoot a few scenes of the dock area and the river. The banks of the Danube in Vienna are a bustling area, and I was able to capture a wide variety of scenes, including some of the towering Vienna skyscrapers which I had not noticed earlier.

That was my last look at Vienna, which we had only a day to see. As with every place we went in Europe, this visit only whetted my appetite for a longer stay.

That night we started on our voyage upriver to the Wachau Valley, the subject of the next couple of posts.