Ephesus was one of the great cities of the ancient world. It was founded by Greek colonists in the 10th century BCE and became the site of the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. It came under Roman rule in 129 BCE. It was an important center of early Christianity, and the Apostle Paul lived there for several years in the early 50s CE. The silversmiths of Ephesus, who made a living from crafting and selling statues of Artemis, felt threatened by Paul’s preaching, and one of them, named Dimitrios, famously instigated a riot against him. The rioters marched to the amphitheater shouting “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” City authorities intervened to prevent Paul from being lynched, but he was imprisoned for a while as a threat to public order and forced to leave Ephesus. The Gospel of St. John may also have been written in Ephesus ca. 90-100 CE. During antiquity Ephesus was one of the greatest seaports of the Mediterranean, and for a time the most important city of the eastern Roman Empire after Constantinople; it was destroyed by the Goths in 263 CE, but rebuilt afterward. Later, however, it began to decline owing to the silting up of its harbor by the Küçük Menderes river, which repeating dredging could not delay indefinitely. In 614 the city was wrecked by an earthquake, and the depredations of Arab and Turkish invaders thereafter completed its ruin.

We entered the ancient city of Ephesus from the east, at the Varius Baths. The spelling of the name is not erroneous; there were not various baths at this location but rather one large bath complex, named after a wealthy citizen named Varius, who forked over the money to build it during the second century CE. The bath complex consisted of three sections: the frigidarium with cold water, the tepidarium with warm water and the caldarium with hot water. There were also resting, sitting and reading rooms.

Just beyond the Varius Baths lay the Odeon, a “small” amphitheater (capacity 1500) commisioned in the second century by Publius Vedius Antonius, a wealthy citizen of Ephesus, and his wife. It was used for political meetings, concerts, theatrical performances, etc.

Ephesus had two agoras, one for state business and one for commerce. The Odeon stood on the north side of the State Agora. Dating from the reign of Augustus (d. 14 AD, this was a 160-meter arcade which hosted both commercial enterprises and law courts. It was connected via three gates to the Varius Baths, presumably so people who felt soiled by their dealings with lawyers could quickly duck out to cleanse themselves.

Just to the west of the Odeon stood the Prytaneion, a government building where receptions, religious ceremonies and banquets were held. It also contained the sacred fire of Hestia, which was supposed to never be extinguished. To that end it was tended by priests called Curetes, who gave their name to the main street which leads from the State Agora down to the main residential district and the Commercial Agora.

Roman rule in Asia was initially quite unpleasant for the Ephesians, as well as all the inhabitants of Roman Asia, who were subject to rapacious taxation and corrupt administration. This created an ideal opportunity for Mithridates VI, King of Pontus, who took advantage of the unrest to invade and massacre the Romans in 87 BCE. The hiatus in Roman rule, of course, was only temporary; in response Rome dispatched the general Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who defeated Mithridates, retook Ephesus and, using the cachet conferred by his army command, went on to make himself dictator of Rome. At the beginning of Curetes Street stands a monument erected by Gaius Memmius during the reign of Emperor Augustus to commemorate Sulla’s reconquest of Asia. Memmius was Sulla’s grandson.

Just off the State Agora was the Fountain of Pollio, so-called because people who had polio were cured by bathing in it. No, I made that up. Actually, it is named for the Pollio family, a prominent Ephesus family who had it built in 97 AD. Unfortunately, the scene was spoiled by a scruffy tourist who happened to be strolling through when Sandie took the picture. You’d think that the Turks would know better than to let such riff-raff into their treasured historical sites.

Near the southwest corner of the State Agora stands the Temple of Domitian, erected in the first century BCE. The name seems to have been given erroneously, since it is now believed to have been erected in honor of the Emperor Titus, who would have been a much better choice than his successor Domitian, a brutal and unpopular tyrant who was killed by one of his servants. The official name was the Temple of the Sebastoi (“venerable ones”), the Greek form of the Roman imperial title Augustus.

Chuck Mattox, who appears in the photo below, on this occasion was wearing a t-shirt he had acquired after a previous eclipse, which he and Elouise had viewed in Austria in 1999. Chuck and Elouise Mattox are inveterate eclipse-chasers; the one in 2006 was at least their fourth – I may have lost track!

From the Temple of Domitian we strolled down Curetes Street toward the residential district. Along the way we noticed columns of smoke billowing from fires set at seemingly random places around the city. We concluded that these fires were set by descendants of the Goths, trying to emulate the exploits of their ancestors, who had burned the city in 263 CE. Fortunately, it was a rainy day (note the distant rain shower in the scene below), and the fires didn’t really do much damage.

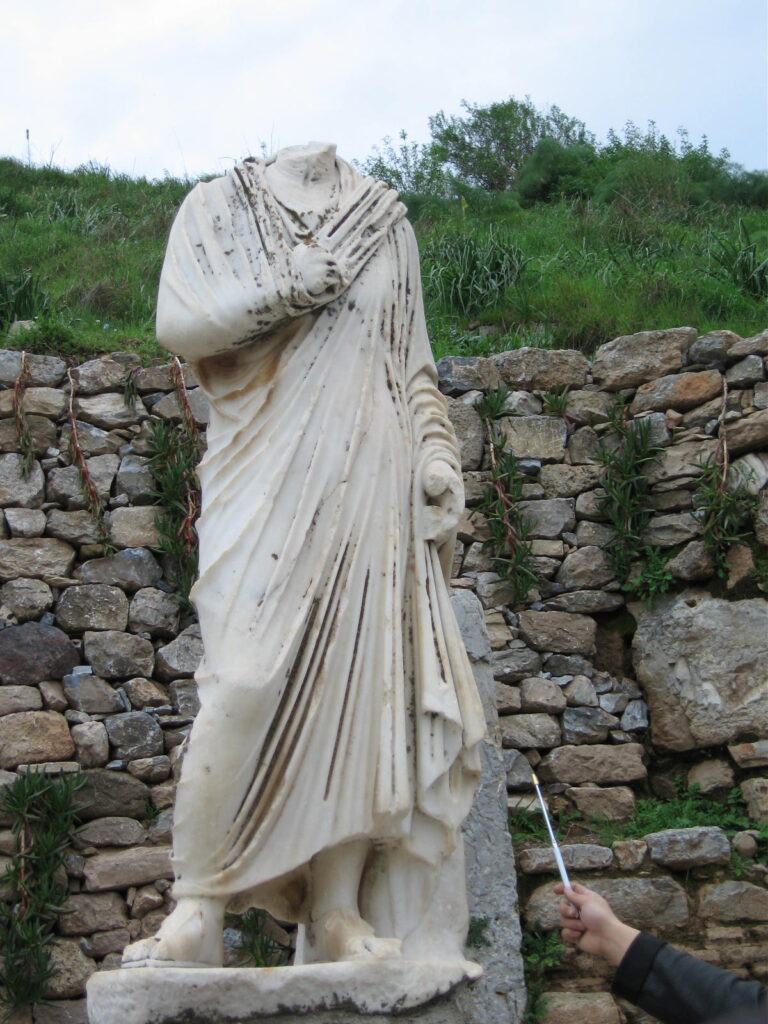

On the way down Curetes Street, we came across a statue of a woman with no head. We found out it had been erected during the Byzantine era in honor of a woman doctor who had rendered great services to the city. It was not known when the head was taken or by whom, but it was common for plunderers to cut the heads off statues since the entire statue was much heavier and hard to cart away.

Curetes Street proved to be a bustling area, just as it must have been in antiquity, with many attractions.

A side entrance to Curetes Street is framed by the Gate of Hercules, which features twin columns with reliefs of Hercules performing one of his Twelve Labors, strangling the Nemean Lion. Hercules had been tasked with killing a lion which had been terrorizing the people of Nemea. The lion had a skin so thick that arrows were useless against it, so Hercules had to strangle it instead.

Beyond the Hercules Gate, we passed the Fountain of Trajan, dedicated to the Emperor who reigned from 98 to 117 BCE), under whom the Roman Empire reached its greatest territorial extent. Originally the fountain was graced by a gigantic statue of the emperor, but now only the feet remain.

Further down on Curetes Street, we came to the residential district, seen at left in the following photo. The exhibits feature excavated interiors of houses, which have been covered with tin and plastic to protect them from the weather. The two-story structure at the bottom of the hill is the Library of Celsus.

The floors of upscale houses in the Roman Empire often contained beautiful mosaics, and some of them still survive in Ephesus.

Toward the bottom of the hill we encountered the Baths of Scholastica. Originally built in the first century CE by Varius, these baths were renamed after a Christian woman who undertook their restoration in the 4th century. They were the largest baths in Ephesus.

One of the best-preserved structures on Curetes Street is the Temple of Hadrian, built around 138 BCE to honor the Emperor Hadrian, who came to visit the city in 128.

The facade of the temple has four Corinthian columns supporting a curved arch, in the middle of which is a relief of Tyche, goddess of victory.

Near the Temple of Hadrian, Pam Bloxham and Cherie Rabideaux paused to frolic with one of the local felines who inhabited the ruins.

One of the most noteworthy features of ancient Greco-Roman cities was the abundant provision of running water, via the aqueducts built by the Roman authorities. Most houses did not have interior plumbing, but access to water was available via public fountains, baths and latrines. With the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, this amenity was lost and not regained in Europe until modern times.

The toilet facility was conveniently located next to the Scolastica bathss. Unlike modern airport pay toilets, the ancient ones in Ephesus were not coin-operated.

Since most people in antiquity were illiterate, public advertising had to take purely pictorial forms. On Curetes Street we encountered an ad for a brothel embedded in a concrete paving block. The footprint showed the way to go; the purse indicated that the service wasn’t free; and the hole provided a way to measure whether one had enough coins to afford it.

Located near the corner of Curetes and Marble Streets, the Brothel originally contained a figurine of Priapus, suitably endowed. Unfortunately, it was removed to the Ephesus Museum in the nearby town of Selcuk, which we didn’t get to visit.

Below is a shot of another room of the brothel, this time looking through the interior toward the nearby Library of Celsus, with Chuck Mattox framed in the doorway. I have a theory that the altar in the center of the room was where virgins destined for the trade were brought to sacrifice their maidenheads.

Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus was a Roman official of Greek origin, and a native of Ephesus, who served as governor of the province of Asia in 105/106 CE. At his death he bequeathed a large sum of money to have a library built by his son, Julius Aquila Polemaeanus, to serve as his monument and his burial place. The library was completed during the reign of Hadrian, after the death of Aquila himself, and came to hold more than twelve thousand scrolls, making it the third largest in the Roman Empire, after Alexandria and Pergamum. It was also an architectural triumph. The main floor served as a reading room and was lit exclusively by natural light from the windows.

Over the centuries invasions, fires and earthquakes left the library in ruins. In the 1970s archaeologists were able to reconstruct the facade, though the interior remains to be restored.

Next to the Library of Celsus stood the twin Gates of Mazeus and Mithridates, which led to the Commercial Agora. These predated the Library, having been built by two former slaves to honor the Emperor Augustus, who gave them their freedom.

The Commercial, or Lower, Agora is the larger of the city’s two agoras.

The Lower Agora was indeed quite spacious.

Along the east side of the Lower Agora, ran Marble Street, which led to the Great Amphitheater, our next destination.

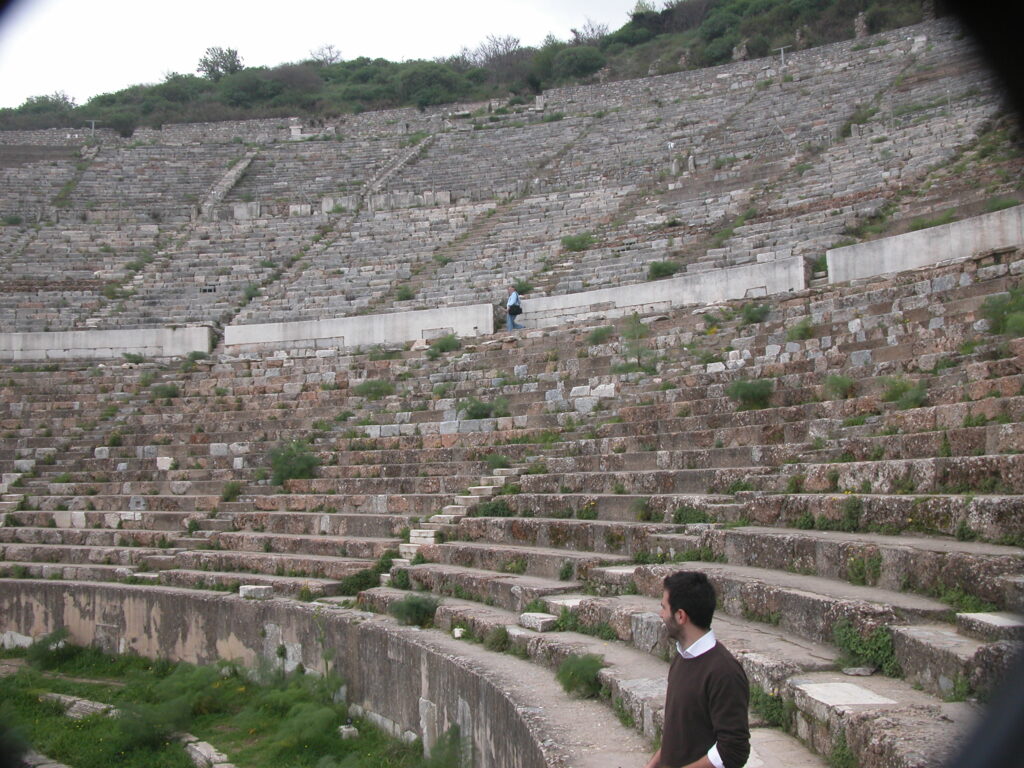

The Great Amphitheater of Ephesus was first built in the third century BCE and expanded and renovated several times during the Roman period. It was the largest in Anatolia, with a capacity of about 25,000 spectators. (By comparison, the Colosseum in Rome could accommodate up to 80,000 people.)

The Grand Amphitheater was built at the base of Panayir Mountain, using the rock of the mountain as a natural foundation for the seating. Other than the Temple of Artemis, which no longer exists, it was the most imposing structure of Ephesus.

The Grand Amphtheater was also the scene of the Riot of the Silversmiths that ended St. Paul’s residence in Ephesus. The next photo provides an idea of the scale of the seating.

From the Great Amphitheater we headed for the site of the Temple of Artemis. Two paltry columns next to a drainage pond are all that remains of what was once one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world.

Near the exit which took us back to our bus, a sign advertised the location of the modern pay toilets, which are coin-operated.