On March 22 Sandie and I flew from LA to Chicago O’Hare to catch our Turkish Airlines flight to Istanbul, along with the rest of the OCSS group. In Istanbul we transferred immediately to our connecting flight to our first tour stop, the city of Izmir, formerly known by its Greek name of Smyrna. In olden times it was famous for its figs, which are still sold (at least in the USA) as Smyrna figs.

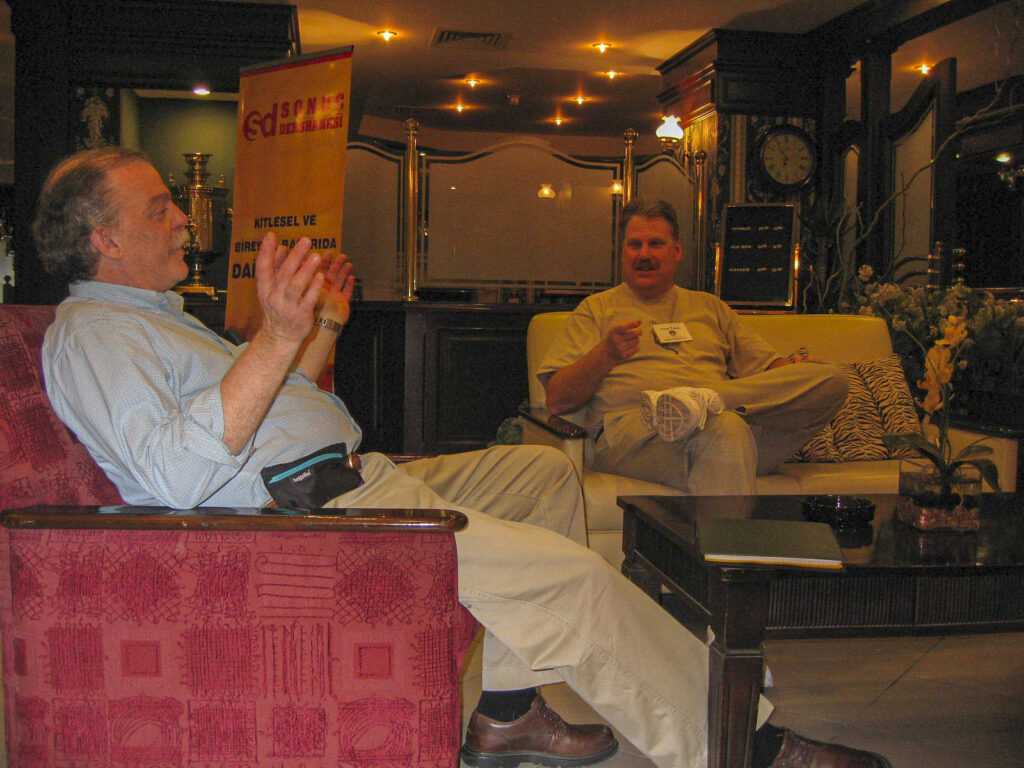

Upon arrival in Izmir, we were greeted by our guide from Troy Tours, Attila Mahur, later dubbed “Attila the Honey.” (The following pages will make it clear why he earned this sobriquet.) He whisked us to our lodging in the Hotel Karaca, where we shook the dust of travel off our feet, figuratively speaking, relaxed in the hotel lobby and began to get to know our fellow-travelers. Some Sandie and I already knew, such as Jim Windlinger of Fullerton, California, seen at right in the photo below; Jim is a member of Orange County Astronomers and a denizen of the OCA Anza observatory site, where now he has an observatory near mine. Others were new, such as Rick Gering of Chicago, at left in the photo.

Another new acquaintance was Marvin Blaski, shown in the next photo.

The exterior of the Hotel Karaca, as seen in the next photo, was unremarkable, but the interior more than made up for it. It was the first and probably least pretentious of the places we stayed in Turkey, but it was more than adequate.

From what we saw of it, Izmir appeared to be a thoroughly modern city. Appearances can be deceptive. The location has been settled since the Neolithic period, over 8500 years ago, and the city has over 3000 years of recorded history. For most of that time it has also been one of the greatest mercantile ports in the Mediterranean area. But whenever I think of Izmir/Smyrna I am reminded of Eric Ambler’s great spy novel The Mask of Dimitrios (published in the USA as A Coffin for Dimitrios). The career of the sinister title character begins in Smyrna at the time of the greatest disaster in its history, the fire which broke out after its capture by Turkish forces from the Greeks in 1922 and destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, and the accompanying forced evacuation of the population of those quarters. Subsequently, the city was rebuilt and is now the third largest in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara.

In fact, to exterior appearances Izmir could have almost have been a city in Italy or Greece. In particular, women generally went out unveiled and unescorted, typically dressed in Levis and other trendy European clothing.

We saw very little of Izmir proper during our stay there, since we spent most of our time in Ephesus and the Aegean Free Zone. Most of our photos of the city were taken by Sandie from the bus with her versatile little Canon camera.

At the end of World War I, the victorious Allies dismembered the Ottoman Empire and parceled out its components to various members of the alliance via the Treaty of Sevres of 1920. That was how the British got the Mandate for Palestine and Iraq and the French got control of Syria and the Lebanon. The western parts of Anatolia, where Greeks had been living since time immemorial, were promised to Greece, but it didn’t work out that way. The Greek Army, anticipating the treaty, landed forces in Smyrna in 1919, but they underestimated the recuperative powers of the defeated Turks, who began a national revival under the leadership of the formidable Mustafa Kemal, later known as Ataturk. In 1922 Ataturk’s forces routed the Greeks, drove them out of Anatolia and retook Smyrna. The attendant violence and the fire which broke out four days after the Turkish capture of the city resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of Greek and Armenian civilians, and all of the remainder who could fled. Many additional thousands, unable to find or afford passage aboard the few ships which would accept refugees, perished in the terrible conditions of those days. In Ambler’s novel, the fictional Dimitrios obtains the money to buy his passage aboard a ship in the harbor by killing a Jewish moneylender and framing a Turk for the crime. One of the non-fictional survivors was Aristotle Onassis.

Following the victories of Mustafa Kemal, the new Turkish Republic founded under his leadership renounced the Treaty of Sevres, which was then superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923. By its terms Turkey retained control of Anatolia, including Izmir, and the Greek and Armenian communities which had existed there for centuries were never re-established.

The disasters of the Greco-Turkish War caused the population of Izmir to shrink from around 300,000 to half that number, and it did not regain its former size until after World War II; but since then it has grown, largely by emigration from the interior of Turkey, to around 3 million. The city also now incorporates a number of ancient sites such as Pergamon, Sardis and Ephesus, the last of which which we visited on the following day.