Évora is overall a far more cheerful place than you would guess if all you ever saw of it was the Capela dos Ossos. From there we walked toward the center of town, our path leading down a street lined with cafés and boutiques which proved to be Évora’s equivalent of a shopping mall – I have to say it was a welcome relief from actual shopping malls. The shops featured local wares such as ceramics and cork purses. Évora is in the cork-oak country of southern Portugal, which produces 50% of the world’s supply of cork. Unfortunately for the cork producers, winemakers in recent years have taken to plugging their bottles with stoppers made out of material other than actual cork, which has forced the cork makers to find other markets for their wares. Cork, it turns out, is very durable and versatile and can be made into attractive and sturdy shoes, wallets, purses and other useful items. I purchased a cork purse for Sandie and several other items to take home as gifts for friends and relatives.

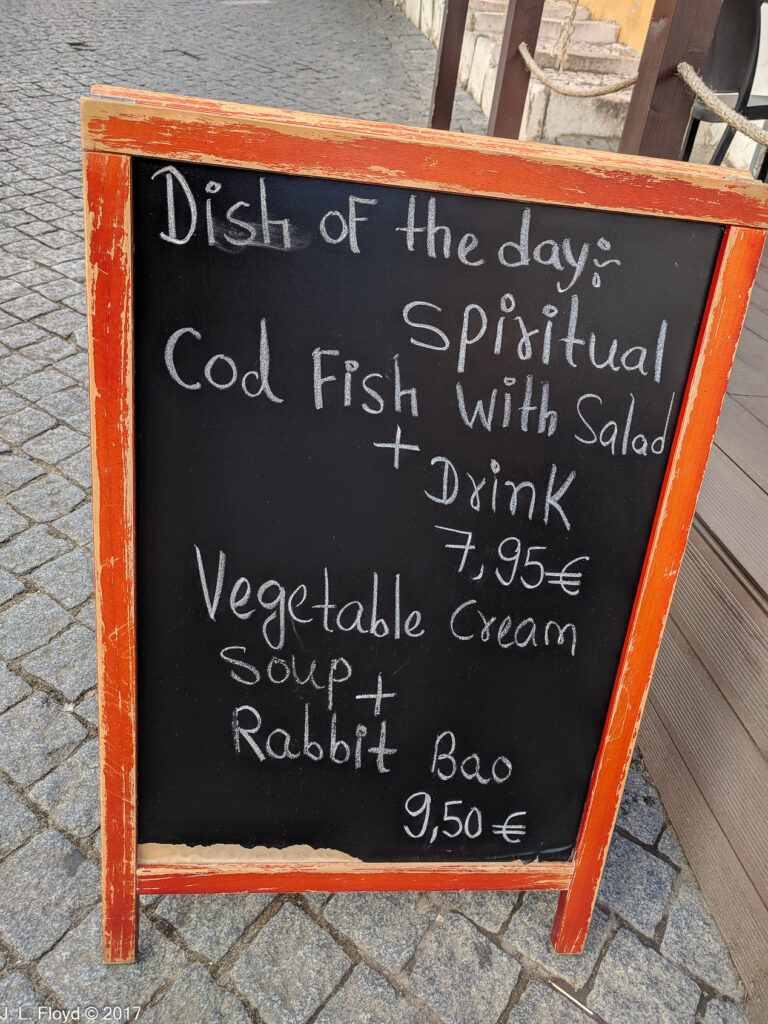

But it wasn’t necessary to spend money to enjoy strolling through the tourist-oriented district of Evora. The streets were paved with locally quarried stones laid out attractively in stripes of alternating colors – granite for black, limestone for white – and sometimes in intricate mosaic patterns as well. One boutique had a sign in the window that said “Don’t grow up – it’s a trap!” I found myself in full agreement with that statement. One of the cafés along the street had set out a menu advertising “Spiritual Codfish” for lunch. I couldn’t imagine what could be spiritual about codfish, and I didn’t have an opportunity to sample it to find out.

We emerged from the semi-pedestrian shopping street onto Praça do Geraldo, the main square of Évora. It is named for Geraldo Sem Pavor, Geraldo the Fearless, who retook Évora from the Moors in 1165. It is surrounded by several churches, palaces and various public buildings. The square was used, and is still used, as a venue for festivals, fairs, and other public celebrations. In days of yore it was also used for public executions and autos-da-fé.

Upon reaching the square, we gathered in front of the local branch of the Bank of Portugal, where our local guide related information about the history and layout of the square. Then we were free to wander around and savor the myriad attractions of the town center.

I noticed a sign prominently placed in the middle of the square featuring the hammer and sickle of the PCP – the Communist Party of Portugal. It seemed to indicate that the Party was in favor of Salaries, Employment, Production, and Sovereignty, and called for a Minimum National Salary of 600 Euros. This didn’t seem to be a very radical agenda in the tradition of Lenin and Stalin. Nevertheless, recalling that during medieval and early modern times Geraldo Square had been a place where public executions of criminals and heretics had been held, I proposed to our local guide that an auto-da-fé be staged to have all the Commies burned at the stake. However, it turned out that the Inquisition had been disbanded in 1821, and no Inquisitors were available nowadays to round up the usual suspects.

In any case we were too busy savoring the many attractions of Geraldo Square and its environs. We checked out Évora Cathedral, one of the Gothic masterpieces of Portugal, built between 1280 and 1340. We found an ice-cream shop which appeared to practice a novel way of snaring customers: the management had barricaded the narrow street with tables and chairs, blocking it so that pedestrians had to pass through an obstacle course calculated to exhaust them and make them stop for refreshment. And we found the ruins of the city’s ancient Roman temple, sometimes mistakenly called the Temple of Diana. Built in the first century CE, it was actually probably dedicated to Augustus, the first Roman Emperor. Unfortunately, we didn’t get to see much of it because it was covered with scaffolding while repairs were in progress. But you can see nice pictures of it here.

Next to the temple is another landmark of Évora, Lóios Convent and Church. That is, it was built in the 15th century to be a convent and church. The church is Gothic, but in the 18th century the interior was covered with azulejos – ceramic tiles. In 1965 it was converted into a pousada (luxury hotel).

Alas, we had too little time to explore Évora as fully as it deserved, and soon the call came to reboard our tour bus and embark on the next leg of the journey, which would take us to the Spanish border. On the way back to the bus, we took final snapshots of the medieval walls of Évora, which still partially encircle the city. Sandie also captured a shot of the Prata Aqueduct, an imposing structure built in the 16th century. It was designed by military architect Francisco de Arruda, who also designed the Tower of Belem in Lisbon. We didn’t find out why it bears the name Prata, which means “silver” in Portuguese (cf. Spanish plata – Portuguese tends to use “r” sounds where Spanish uses “l”). I have a theory that it was named after a friend of mine who teaches engineering at USC and maybe traveled to Portugal at one time to make some crucial repairs to the aqueduct. I’ll have to ask him about that.

There was still enough daylight left in the short November day to enjoy the ride through the cork-oak country of southeastern Portugal. I’ve already touched on the fact that cork is one of Portugal’s most important products, and nowadays its uses extend far beyond plugging wine bottles (although the cork producers still make extravagant profits from selling corks at exorbitant prices to the French champagne vintners). In addition to fashion accessories such as handbags and shoes, it is made into mats of all kinds, cell phone and tablet covers, musical instruments and baseball cores, and many other unlikely-seeming products such as furniture. It’s an excellent material for insulation and sound-proofing, and so is finding increasing application in such industries as construction and aerospace. It’s also a sustainable, earth-friendly substance: cork is made by stripping the bark from the trunk of a certain type of oak tree, which is then wrapped with cloth to protect it from insects and weather while the bark grows back. This is done only every nine years during the lifetime of the tree, typically 270-300 years. The cork production industry is tightly regulated by Portuguese law, and it is illegal to cut down a cork oak without a special permit, not easy to obtain. You can find out more about cork production here.

By the time we crossed the Spanish border, night had fallen, and we stopped for a bite to eat at a tapas restaurant near the crossing before resuming our journey into Spain. Our objective was the fabled city of Seville, once mistress of a commercial and financial network spanning the world, from the Americas to the Philippines, and now again a vibrant and thriving metropolis.