As a historian, an American and a citizen of the world, I felt an obligation to visit Hiroshima. I wanted to deepen my understanding of what had happened on the terrible day of August 6, 1945, and to pay homage to the thousands who died there as well as the survivors who continued to suffer from the effects of nuclear radiation and social discrimination. And I wanted to see how the city had recovered from the ghastly catastrophe inflicted on it.

I arrived in Hiroshima on the Shinkansen on a sunny April day and immediately found my ryokan, which was a short walk away. It was a very plain, unremarkable room, tucked away in a high-rise building, sort of a cross between a hotel and a traditional ryokan – the only traditional aspect I remember was that the floor was covered with tatami rather than rugs. I have no need for luxurious hotels in any case and I found it quite comfortable for the two nights I was there.

I had a memorable dinner in a tiny hole-in-the-wall restaurant near the hotel. It was a bar-and-grill type of place where you sit at on stools at the bar and the food is cooked right in front of you. The specialty of the house was oekenomiyaki, a type of pancake featuring all sorts of ingredients cooked together in a delicious melange. The oekenomiyaki were exceptionally tasty as well as inexpensive, and I downed them with beers, none of which I paid for; as soon as the other patrons noticed a gaijin in the bar they started buying me beers and continued to do so for the rest of the evening. I felt honored beyond measure and I’ll always be grateful for the hospitality and good feelings accorded to me in Hiroshima.

Next morning I began my explorations at the Genbaku (Atomic Bomb) Dome, aka the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. Prior to August 6, 1945 it was known as the Hiroshima-ken Sangyo Shoreikan, the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, built in 1914. Since then it has been preserved in a state as close as possible to its condition immediately after the bombing: a ruined skeleton. The intent was to preserve it as an overwhelmingly powerful symbol of the destructive power of which humans are capable, but also as an expression of hope for peace and the ultimate elimination of nuclear weapons (and, I would add, of all weapons of war) from the world.

The Industrial Promotional Hall was neither the intended target nor the actual ground zero of the atomic bomb. The intended target was the Aioi Bridge over the Ota/Motoyasu River, a few hundred feet away. The actual hypocenter was the Shima Surgical Clinic 800 feet to the east of the bridge and 490 feet east of the Industrial Promotional Hall. The bomb did not actually hit anything because it exploded 1,900 feet in the air over the hypocenter, but the blast leveled almost 70 percent of the buildings in Hiroshima and killed about 80,000 people, 30% of the city’s population. The Little Boy fission bomb dropped on Hiroshima was a primitive weapon by today’s standards, since only 1.7% of the fissionable material aetually ignited, a fact which would have been of little consolation to its victims. I mention this only to underline the apocalyptic nature of nuclear warfare and to reinforce the case for not engaging in it.

Whenever I saw happy schoolchildren like those in the following pictures I could not help thinking about other schoolchildren who perished on August 6 in Hiroshima and on August 9 in Nagasaki. I’d rather it didn’t happen again.

But the nuclear attacks weren’t really much different in their effect from the holocaust that occurred in the firebombing of other Japanese cities – such as Tokyo, where on March 9-10, 1945, the single most destructive air raid in human history resulted in the deaths of over 100,000 civilians. Such horrors might be considered just retribution for the Japanese invasion of China, during which millions of Chinese civilians and soldiers perished. But that leads into a long chain of cause and effect which involves the impact of 19th-century Western imperialism in East Asia and elsewhere, and I’m not going there. The point here, the lesson of Hiroshima, is that this madness has to stop. Nations have to learn to cooperate rather than destroy one another. Otherwise there is no future for humanity on this planet. Are you listening, Vladimir Putin?

The Hiroshima Peace Park, located on an island across the river from the Genbaku Dome, reinforces this message. It contains a museum and a number of monuments. Near the entrance of the museum is a clock with the hands frozen at 8:15, the time the atomic bomb went off. The exhibits and information include coverage of events leading to the war, Hiroshima’s role in the war, and of course the bombing and its effects.

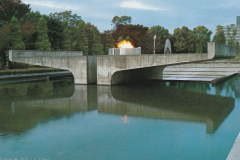

In the center of the park is a cenotaph – an empty tomb commemorating people whose remains are buried elsewhere – honoring the victims of the bomb, whose names are recorded there. A concrete arch, representing a shelter for the souls of the victims, covers the cenotaph. There is a second cenotaph in the park for Korean victims of the bomb; there were some thousands of Koreans working as co-opted laborers in Hiroshima at the time of the bombing.

In front of the cenotaph there is also a Flame of Peace, ignited in 1964; it is supposed to continue burning until all nuclear weapons have been eliminated from the world.

There is also a Peace Bell, located in a gazebo in the park. Although it was donated by the Greek embassy, it is a Japanese-style bell cast in Japan. On it are inscriptions in Greek, Japanese and Sanskrit. Visitors are encouraged to ring it, which they do often.

The most poignant monument in the park is the Genbaku no Ko no Zō, the Children’s Peace Monument, built in 1958 with funds donated by Japanese school children. It commemorates all the children who perished from the atomic bomb, but especially Sadako Sasaki, a girl who was two years old when the bomb struck, and later died of leukemia contracted as a result of radiation exposure. Before she died in 1955, she undertook a project of folding a thousand origami paper cranes (senbazuru). In Japanese legend, the crane is a magical bird, living for a thousand years, and a person who folds one thousand origami cranes in a year will be granted a wish by the gods (in some versions of the legend, long life or eternal bliss). There is some uncertainty about whether Sadako completed the project before she died—family members say she did—but in any case she passed away at the age of 12, and the Children’s Peace Monument honors her memory. A statue of Sadako stands on top of the monument, holding a wire crane above her head. From the ceiling of the gazebo-like monument structure hang sheafs of paper cranes on strings, contributed by children from all over Japan and from around the world, and continually replenished as they succumb to the weather, and thousands more are stored in glass boxes around the monument.

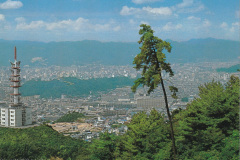

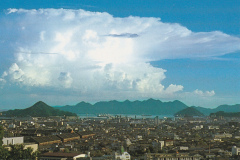

While the Genbaku dome and Peace Park in themselves provide sufficient reasons for going to Hiroshima, there are other incentives also. Not the least important is the island of Miya Jima, across the bay from Hiroshima, but I am giving it a page of its own, so I’ll end this page with a few scenes from around the city. Some of these, representing views I was not able to see or photograph in person, are taken from photos I did not take personally but acquired by other means. Unfortunately I’m unable to give proper credit to the sources as I no longer have the originals from which the pictures were digitized.

I should note in passing that Hiroshima is also the site of the headquarters of Mazda Motor Corporation, though I was unaware of it at the time, so I don’t have any pictures to show for it.