Miya Jima is a small island across the bay from Hiroshima. It is the site of Itsukushima Shrine, one of the most famous in Japan, and a place of spectacular beauty.

One reaches Miya Jima by taking a ferry from Hiroshima harbor. The trip takes less than half an hour and is worth going on in itself.

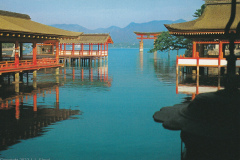

Itsukushima Shrine is most famous for its “floating torii,” the red-orange gate built a few feet off the shore which at high tide appears to be floating in the water. At low tide, one can see the base anchored in the mud of the sea bottom. The buildings of the shrine itself extend over the water, constructed on piles driven into the sea bottom. I would guess that in a few years their interiors will be flooded by rising sea levels. The torii and the shrine proper present a striking appearance as one approaches the shore and are equally stunning as seen from the shore itself.

At the water’s edge near the shrine, I encountered sika deer being fed by local women. As in Nara, the deer are considered sacred – indeed, so is the entire island, and everything on it. For example, trees are sacred and may not be cut down.

The island is also part of Setonaikai National Park, the largest national park in Japan, a huge area which encompasses 3,000 islands and the waters around them.

After touring the shrine, I wandered about the paths of the lower island for a while before taking the sacred cable car to the top of the sacred mountain, Mt. Mizen. Early on I encountered a colorful statue out of a comic book, looking somewhat like a pirate, who appeared to be directing traffic or, more likely, telling cars to turn around and go home. I never found out who this figure was supposed to represent, but he was a welcome relief from the general solemnity of the shrines.

Shortly afterward I came across Toyokuni Shrine with its striking red five-story pagoda, built in 1407, which I had glimpsed earlier from the ferry. It stands near the Senjokaku Pavilion, the largest building on Miyajima; its name means “Thousand-tatami pavilion.” Its construction was initiated by Hideyoshi Toyotomi (the “Taiko” Nakamura of Clavell’s novel Shogun) in 1598 as a place for chanting Buddhist sutras for Japanese warriors killed in battle in his many campaigns. Hideyoshi was the second great unifier of Japan at the end of the chaotic Sengoku Jidai period of the 16th century; he was a talented general of peasant origin who quickly put down the rebellion of Akechi Mitsuhide, assassin of Oda Nobunaga, and in short order repeated Nobunaga’s achievement in bringing the powerful warlords, the daimyo, to heel. Then, in 1592, to keep the daimyo occupied and glorify himself, he undertook an invasion of Korea, conceived as a first step toward the conquest of Ming China and then of all East Asia, if not the world. After spectacular initial successes, the invasion was frustrated first by the decrepit but still functioning Ming government, which dispatched a relief army to the aid of the Koreans; and finally by the Korean navy, under Admiral Yi Sun-sin, which eventually destroyed the Japanese fleet, leaving the Japanese army stranded and unable to resupply itself. When Hideyoshi died in 1598, the regents who first took over from him ended the Korean adventure and discontinued work on the Senjokaku Pavilion, which was also left unfinished by the succeeding Tokugawa Shogunate. In 1872, following the Meiji Restoration, the Senjokaku was converted to a Shinto shrine and rededicated to the memory of Hideyoshi.

Near the 5-story pagoda and the Senjokaku Pavilion stands a small but elegant Shinto shrine, the name of which I never found out.

While wandering amidst peaceful rustic lanes teeming with cherry blossoms, I stumbled into beautiful Momojidani Park, famed for its more than 200 maple trees of several different species. In autumn, when the maple leaves turn red, yellow and orange, the park presents a riot of color. It is a mecca for picnickers and also has one of the loveliest bridges in Japan.

From Momojidani Park it was a hop, skip and a jump to the cable car terminus at the base of Mt. Mizen. (They call the cable car a “ropeway,” but the ropes are of course steel cables.) It has two stops, one halfway up the mountain and another near the top. I got off at the first terminal and took a stroll along the paths there, before continuing on to the upper terminal.

The observation deck at the top of Mt. Mizen affords breathtaking views of Hiroshima Bay and the Inland Sea.

I wandered around the paths near the summit of Mt. Mizen for a while. This was the area that the sacred monkeys – Japanese macaques – were said to frequent, and indeed there were signs posted cautioning visitors to be wary of them, not to feed them, not to approach them, and even to avoid looking them in they eye – apparently they tended to regard that as a challenge. I had no problems; the few monkeys I saw were not interested in me or much concerned about my presence, and went about their business as if I were not there. However, Dave Winter said it was much different when he was there; wherever he went, the monkeys were lurking and they always looked him in the eye – he couldn’t avoid it. Maybe it had something to do with the season or phase of the moon. I have since read, however, that in 2010 the authorities decided to round up and deport the monkeys from Mt. Mizen, Stalinist-style, without asking them their preference, and transplant them to the Japan Monkey Center in Aichi Prefecture, near Nagoya. Actually, there was some justification for this, because it has since been determined that the monkeys had been watching Planet of the Apes and had thereby been inspired to plot the overthrow and subjugation of humans. Unfortunately, evicting the macaques from Mt. Mizen did not succeed in foiling their schemes; more recently, in Yamaguchi, a city down the coast from Hiroshima, a serious of ominous attacks on humans by macaques has taken place. Should anyone be unduly perplexed by this, I would like to point out that monkeys are primates, closely akin to humans, and share many of the vices and foibles of that species, including a penchant for violence. Also, one may speculate that the radiation released by the atomic bomb in 1945 quite likely could be responsible for many mutations among the fauna of southern Honshu, including the macaques, who may have had their evolution thus accelerated to develop more advanced intelligence, and used it to conclude that maybe they should get rid of humans before humans exterminate all other primates as well as themselves.

I returned to Tokyo the next day aboard the super-fast Nozomi Shinkansen. While waiting at Hiroshima Station to depart, I shot a few pictures of the train in the terminal before boarding the train. To my surprise, there was someone asleep in the seat that my ticket assigned to me. I felt reluctant to wake him up and ask him to move, but fortunately just at that moment someone came up and asked me, “Can I help you?” This was a frequent occurrence in train and metro stations in Japan – people were extremely helpful and liked to practice their English – and I explained the problem, showing him my ticket with its seat assignment. He looked at it and said, “Oh, this is the Hikari. You want the Nozomi!” He thereby saved me from an embarrassing mistake – otherwise I might have found myself several hundred miles up the line on the wrong train, going to the wrong place.

The Nozomi sped me back to Tokyo at 180 miles per hour, covering the 821 km/513 miles in about five hours (stopping in Kyoto). I was able to shoot a few pictures from the train windows – mostly rather boring scenes of Honshu farmland, but at least I was able to verify that there are open spaces in Japan. Unfortunately I fell asleep and missed a great shot of Mt. Fuji, waking just in time to see it go by but too late to grab my camera and set it up for the picture before it disappeared from view.

I am quite disappointed that high-speed trains of the Shinkansen type have not caught on in the USA. Long-distance travel in the United States is far too dependent on airlines, which seem to be getting more crowded, expensive and unpleasant with each passing year. The high-speed trains I have taken in Japan and Europe are far more pleasant and comfortable to ride than any airplanes I’ve been on. It’s obvious that the vast distances of the North American continent limit the applicability of train travel to the longest trips, such as coast-to-coast. Yet for short and medium distances, such as LA to Las Vegas or San Francisco, trains would seem to be a far better choice than airplanes. Yet the California high-speed rail project, which was projected to enable travel from LA to San Francisco in 3 hours, has so far taken 14 years and $5 billion to lay tracks to…nowhere. Originally projected for completion in 2020, it’s now estimated to be on-line by 2030, but only from Merced to Bakersfield. More ambitious plans for a nationwide high-speed train network during the Obama administration foundered on a combination of inexperience, mismanagement and political opposition. Critics never tire of pointing out that the countries where high-speed rail has been successful generally have more centralized or authoritarian governments than the US, where the competing jurisdictions of federal, state and local governments, in addition to the cost of purchasing land from private owners, drives the cost of building high-speed railways to astronomical levels and dictates that rail travel will always be uneconomical compared with automobile and air. I don’t buy this. Autos and airplanes are currently dependent on fossil fuels, which are obsolescent and must be eliminated as a major energy source if humans are to survive on this planet. Even if electric cars and trucks replace gasoline and diesel-fueled vehicles, and hydrogen becomes a viable fuel for airplanes, trains make more sense in lots of ways.