Sandie and I flew into Lisbon on the morning of November 4 and were met by a jovial native of Madrid named Manuel Sueiras, who would be our tour leader. He dropped us off at our hotel, the Novotel Lisboa, and encouraged us to start seeing Lisbon on our own, while he rounded up the remaining members of the tour group, who trickled in as the day wore on.

We hopped into a taxi and went to lunch in central Lisbon, somewhere on the Avenida da Liberdade, but we were too tired from the long flight to follow Manuel’s suggestion any farther, so we returned to our hotel and acquainted ourselves with its amenities, primarily the bed.

We took it easy until later in the day, when everyone assembled in the hotel lobby for our introductory meeting, followed by an inaugural banquet at a nearby restaurant, the Pano de Boca. The name translates literally to “cloth of mouth,” in other words “napkin,” or its more elegant French equivalent, “serviette.”

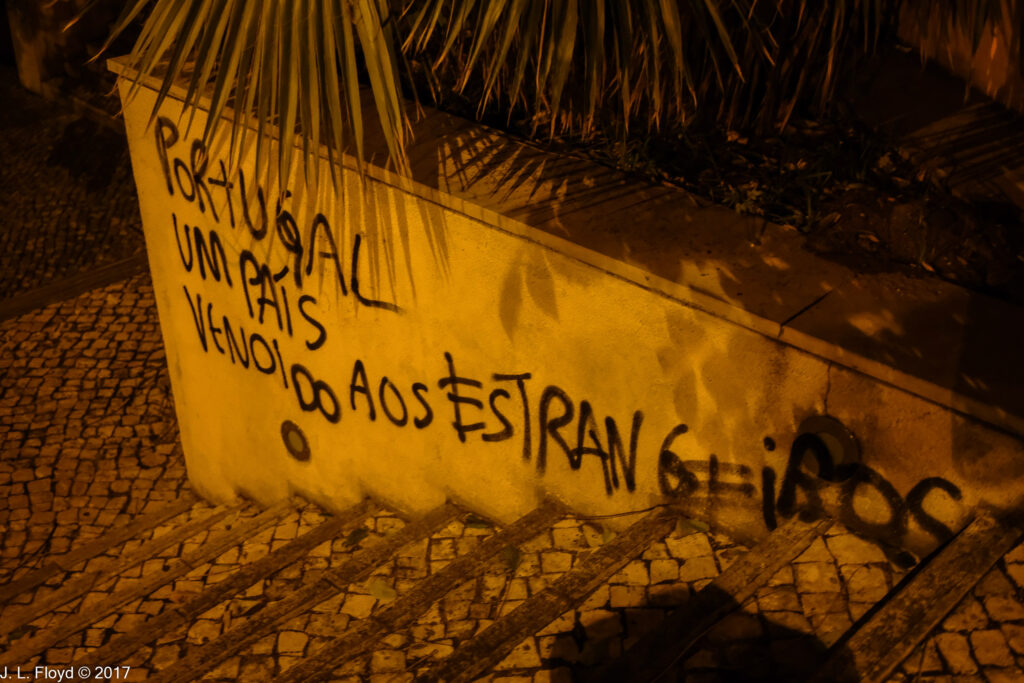

It was already dark when we walked to the restaurant. On the way we passed several interesting landmarks, most notably the Lisbon Central Mosque. This is a very distinctive ultra-modern structure, inaugurated in 1985, and is Europe’s third-largest mosque outside Turkey. It features a highly unusual spiral-shaped minaret. We also encountered a sinister figure, known as The Masked Malefactor, who stalks Lisbon at night; some say that he is the Portuguese equivalent of El Zorro, California’s version of Robin Hood. His photograph is included in the gallery following. But he did NOT write the graffito in the next photo, which reads “Portugal – um país venoido aos estrangeiros.” I’m not sure what the author of this oeuvre was trying to say – my best guess is “Portugal – a country sold to foreigners”. If so the fourth word should be “vendido”. But the graffitist wasn’t necessarily fully literate. Neither am I in Portuguese, but I wouldn’t make that mistake.

At the Pano de Boca the libations flowed freely and we were introduced, among other delicacies, to the Portuguese national dish, bacalhau, which is a preparation of dried, salted cod. It can be prepared in many different ways; some say there are over a thousand recipes for bacalhau. (It should be noted that Portugal is credited with the highest consumption of fish per capita in the European Union.) I enjoyed my fill of it at the Pano de Boca. I’m usually happy as long as the wine flows freely, as it did on this occasion, but it was a special treat to experience my first taste of real Portuguese cuisine.

Next day, refreshed from a night’s rest, we embarked upon our tour of Lisbon. I should mention that in each place we visited, in addition to Manuel, we had a local guide who was intimately acquainted with the attractions and expounded upon them in exquisite detail. In Lisbon our local guide was an attractive blonde woman whose name I unfortunately cannot remember, but I haven’t forgotten her vivacity and eloquence.

One of the first things to know about Lisbon, which most people aren’t aware of — though I myself am well acquainted with it from reading Voltaire’s Candide — is that on 1 November 1755, All Saints Day, Lisbon was struck, and essentially destroyed by, one of the greatest earthquakes in recorded history, a magnitude 9 temblor. The earthquake and the resulting tsunami and fires caused up to 50,000 deaths. As Voltaire noted in Candide, the earthquake struck in conjunction with an auto da fé conducted by the Portuguese Inquisition, which might have been taken to signify divine displeasure with the persecution of heretics; but that didn’t happen, any more than the destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588 persuaded Philip II that it wasn’t part of God’s plan to suppress heresy in England and Holland. However, at least the Marquis of Pombal, who presided over the restoration of Lisbon after the earthquake, did abolish autos-da-fé in 1773, though the Portuguese Inquisition itself was not terminated until 1821.

Quite significantly, King Joseph I and his chief minister, the aforesaid Marquis de Pombal, saw the destruction as an opportunity to build a new city free of the constraints of its medieval inheritance; they adopted a design which envisioned expansive public squares linked by broad avenues, lined with structures built to be earthquake-resistant. The results were enduring, and the present appearance of Lisbon can in large part be traced back to the Pombaline rebuilding of the 18th century.

We first visited a relatively low-key, indeed almost tranquil, location – the Parque Eduardo VII, or King Edward VII Park. The eponymous king was not Portuguese but English, and the park was named for him because of a visit he made to Lisbon in 1903 to reinforce Anglo-Portuguese relations and reaffirm a long alliance between the two countries — Britain having been Portugal’s staunch ally against France during the Napoleonic Wars a century earlier. The park constitutes a long north-south rectangle, at the north end of which is an observation deck with an expansive vista southward down to the Tagus River. There also is a monument, Ao 25 de Abril (“To the 25th of April”), which commemorates the Carnation Revolution of 1974, when the authoritarian Estado Novo regime was overthrown. Over it flies the largest Portuguese flag in the world.

At the south end of the park stands a monument to Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, the Marquis of Pombal. He was a scion of the country gentry who rose from obscurity to become head of the diplomatic service, and eventually the chief minister of King Joseph I (r. 1750 – 1777). He secured his pre-eminence primarily by his management of Lisbon’s recovery from the earthquake of 1755. He was for the most part a proponent of the 18th-century Enlightenment, and implemented significant reforms, over the opposition of reactionary aristocrats. He also gave his name to the style of architecture associated with the reconstruction of Lisbon. We encountered numerous examples of Pombaline architecture during our excursions around the city.

Present-day Lisbon has a population of half a million (545,000) within the city limits, but the greater Lisbon area is home to over three million. It is patently one of the great cities of the world, one of the oldest European capitals, and was the hub of a great colonial and commercial empire from the sixteenth century down to the mid-twentieth. For my part, I found it to be a beautiful, prosperous and richly endowed metropolis. Before moving on to focus on the specific major attractions, I’m presenting a panoply of random landmarks and scenes Sandie and I captured on camera – mostly from the windows of our tour bus – as we wended our way around the city.

I’ll make just a couple of notes on these random shots. The Ponte 25 de Avril, or 25 April Bridge, spanning the Tagus River, was built in 1966 and originally named for Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, who ruled as dictator of Portugal from 1932 to 1968. Salazar died in 1968 and his Novo Estado regime was eventually overthrown in the Carnation Revolution of April 25, 1974, so called because people drove out Salazar’s successors by throwing carnations at them, just like Pepperland citizens got rid of the Blue Meanies in the Beatles movie “Yellow Submarine.” The Salazar bridge was then renamed the 25 April Bridge. Later another bridge was built across the Tagus, a much longer one, upstream of the 25 April Bridge; it is named after Vasco Da Gama.

We frequently encountered election posters sporting the hammer and sickle of the Communist Party of Portugal. I remarked to our guide that I thought we had pulled all the Commies’ arms and legs off at the end of the Cold War, but she informed me that Portugal still has a vibrant and vital Communist Party. (I don’t recall seeing any such posters in Spain, though.)

From King Edward VII Park, we moved on to the Belém district, the site of some of Lisbon’s most famous and historic monuments. The most iconic, one that is always pictured in travelogues (including this one), is the Torre de Belém, officially the Torre de São Vicente. It was built by order of King Manuel I (1469-1521), as a fortification to reinforce the defenses of Lisbon at the mouth of the Tagus River, and completed in 1519. It proved its worth, or lack thereof, in the succession crisis of 1580. Two years prior, in 1578, Sebastian I, the childless King of Portugal, had foolishly undertaken a crusade in Morocco and was killed in battle. His uncle, who succeeded him as king, was a cardinal of the Roman Catholic church, and died two years later, also leaving no heirs. King Philip II of Spain, whose mother was a Portuguese princess, then claimed the throne and sent the Duke of Alva with an army to enforce his claim. The garrison of the Torre de Belém surrendered after only a few hours of resistance, causing Philip II to refer to it as “useless” and order plans drawn up to replace it with something more substantial (which never materialized). From that time the Torre was used as a prison until 1830. In the later 19th century it fell into decrepitude, but was extensively restored in the 20th.

The Belém Tower was originally built on a small island in the Tagus, just off the riverbank, but in the centuries since then development has moved the shoreline toward the island, so that it now appears to be a mere peninsula, or rather peninsulette (if that’s a word). Along with the Jeronimos Monastery and a few other sites (most of the rest having been leveled by the 1755 earthquake), the tower is considered one of the principal examples of Manueline architecture (King Manuel I having been its chief sponsor), a sumptuous style characterized by complex ornamentation in portals, windows, columns and arcades. Starting with Portuguese Late Gothic, it incorporates elements of various other styles, and initiates a transition to Renaissance architecture.

The line to get into the Tower was rather long, and one woman apparently tried to circumvent it by using her cloak as a parasail. It didn’t work.

The Torre de Belém is on the north bank of the Tagus; from there we had a wonderful view of the river and is south bank. It was easy to imagine Vasco da Gama departing in his caravel on the voyage that would take him to India, initiate a global colonial empire, and establish Lisbon as one of the great commercial centers of the world.

A short walk from the Torre de Belém one encounters what looks like an old biplane equipped with floats to land in the water. This is a British-made Fairey III-D Mark II seaplane named the Lusitania (“Lusitania” is the Latin name for Portugal). It serves as a monument to Gago Coutinho and Sacadura Cabral, two Portuguese aviators who completed the first aerial crossing of the South Atlantic Ocean in 1922. They set out from a naval air station near Belém Tower and island-hopped over the Canaries and other Atlantic islands toward Brazil. Upon reaching the first islands in Brazilian waters, they tried to land in rough seas, but the plane sank. Fortunately, the aviators were saved by a Portuguese cruiser which had been sent to support the mission. Another Fairey III, named the Pátria, was sent from Portugal, and they were able to resume the journey. Unfortunately, engine failure brought them down again in the middle of the ocean, and the Pátria was lost; this time they were rescued by a British cargo ship. This time the Portuguese government dispatched a third Fairey III, the Santa Cruz , aboard another Portuguese cruiser. After it arrived they resumed their journey, and the third time proved to be the charm. They made landfall at Recife, Brazil, and flew on to Rio de Janeiro, arriving on 17 June 1922, arriving two and a half months after their departure on March 30. The Santa Cruz, the only one of the three planes to survive the journey, is now housed in Lisbon’s Maritime Museum, which we did not visit; a very realistic replica of the original Lusitania was made to put on display near Belém Tower.

I can’t help but marvel that less than half a century after the first aerial crossing of the South Atlantic, jet airplanes were making nonstop flights across entire oceans and continents, whereas four centuries separated the first circumnavigation of the globe and the invention of the airplane, and thousands of years lapsed between the invention of the sail and the voyages of Columbus and Magellan. Technological progress has accelerated at an astounding pace. Will it continue to do so, and if so, what will the future be like?

A propos of voyages, no less significant than those of Columbus and Magellan were those of the Portuguese, who began the Age of Discovery and were the first actually to reach the East Indies. Their exploits are commemorated with the Padrão dos Descobrimentos, or Monument to the Discoveries, which stands a little way down the shoreline to the east of the Tower of Belém. Unlike the Tower, it is a modern creation, originating in 1939, when a temporary version was created for an exhibition celebrating the 800th anniversary of the founding of Portugal and the 300th anniversary of the restoration of its independence from Spain. That version was demolished after the exhibition closed, but a larger version was completed in 1960 in connection with the commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the death of Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460), who sponsored the early Portuguese voyages of discovery.

Both the original and the current versions of the monument are the work of the Novo Estado regime of Antonio Salazar, and as such are an idealized version of the Age of Discovery, glossing over the myriad hardships suffered by the explorers during their voyages, not to mention the torments they inflicted on the peoples they encountered. The monument is a huge concrete slab, 52 meters (171 feet) high; it takes the stylized form of a caravel, the type of ship used in the early explorations. The base represents the hull of the ship, with a statue of Prince Henry standing in front, and the top of the monument depicts the sails. Lining the sides of the “hull” are statues of various significant figures connected with the voyages of discovery, including Bartolomeu Dias, discoverer of the Cape of Good Hope, Vasco da Gama, discoverer of the sea route to India, Luis Vaz de Camões (Portugal’s greatest poet, who celebrated da Gama’s voyages in his epic poem Os Lusiades), Ferdinand Magellan (who was Portuguese, though he sailed under the flag of Spain), and Pedro Cabral, discoverer of Brazil. There are 33 figures in all; in addition to the major explorers, they include members of the Portuguese royal family, scientists, artists, cartographers, and missionaries. Some of the people represented are only remotely connected with the discoveries, such as Philippa of Lancaster, an English princess who in 1387 married King John I of Portugal, thereby becoming Queen of Portugal. The marriage cemented what was to become an enduring alliance between England and Portugal. Queen Philippa was also the mother of Prince Henry the Navigator.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but the monument is hollow and contains a 101-seat auditorium, a theater and several exhibit halls, as well as a staircase affording access to the top of the monument. We didn’t know that because for some reason the interior was closed the day that we were there; otherwise I would have attempted to climb to the top and photograph the great views that are available there.

We did however enjoy the open square on the north side of the monument, which features a Rosa-dos-Ventos (compass rose) 50 meters (160 feet) in diameter, with a 14-meter (45 feet) wide mappa mundi depicting the routes of the voyages of discovery. The cost of constructing the square was donated by the government of the Union of South Africa. Different types and colors of limestone, including a rare variety found only in Sintra – a town north of Lisbon, which we visited in the afternoon – were used to pave the square and constitute the compass rose. The result, to me, is a work of stunning elegance, which I was unable to capture with my camera in its full glory because I had no tear gas grenades handy to clear away all the people on the square who churlishly thronged on it, blocking the view.

Looking west down the north bank of the Tagus from the Padrão dos Descobrimentos, we caught sight of the Museo de Arte Popular (on the right in the picture below) and the tall Farol de Belém (Belem Lighthouse), with the Torre de Belém between them.

Across the Tagus River, just to the right of the southern terminus of the 25 April Bridge, we caught sight of a tall structure with what looked like a cross on top. The cross turned out actually to be a statue depicting Christ with arms stretched wide, as if to embrace the city of Lisbon. The statue is 28 meters/92 feet tall and stands on a pedestal 82 meters/160 feet high. It is part of a complex known as the Santuário de Cristo Rei (Sanctuary of Christ the King), which itself stands on a hilltop 133 meters/436 feet above the Tagus. It was built in the 1950s as an expression of gratitude by the Portuguese for having been spared the horrors of World War II. The monument has been compared to the statue of Christ the Redeemer atop Corcovado Mountain in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which was its inspiration.

Our next stop, after the Padrão, was the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos (Jerónimos Monastery), another landmark associated with the Voyages of Discovery. Since this post is already overly long and cumbersome, I’ll start a new one to accommodate the proliferation of photos we took there.