One cold day toward the end of winter, I went with my girlfriend Vera and our Norwegian friend Sidsel Larsen for a stroll in the area of Chistye Prudy (“Clean Ponds”), in the Basmanny district of Moscow. Despite the name, there is only one pond visible; the others are now all underground, as is the small Rachka river that feeds them. In the seventeenth century they had a different name – Griaznye Prudy, “Dirty Ponds,” because Muscovites used them as a garbage dump. In 1703 Prince Alexander Menshikov, Peter the Great’s crony, bought them, cleaned them up and gave them their present name. Chistye Prudy reminds me of another Moscow pond, Patriarch’s Ponds, which I’ve seen only in pictures (I was once told that it no longer exists, but that turns out not to be true), but which serves as the opening scene of my favorite Russian novel, Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita.

Our main objective on this excursion was a historic structure known as the “Palace of the Boyar Volkov” because it had supposedly been built in the 17th-century by a boyar (magnate of pre-Petrine Russia) named Volkov. In 1973 it was not open to the public. You could only snoop around the outside. Since then, it has opened as a museum, which has its own web page, in Russian. There is even information online in English about the place, although it is a bit sketchy and of poor quality. Without doing exhaustive research, I’ve been able to piece together some of the history of the palace. Legend has it that in the 16th century, a hunting lodge belonging to the tsar had occupied the site, from which Ivan the Terrible issued forth in disguise to spy on his subjects; but there doesn’t seem to be any documentary evidence to support this. Still, I suspect that it existed in some form prior to the usual date given for its construction, in 1698, during the reign of Peter the Great. Peter conferred it first on his vice-chancellor, the diplomat Peter Shafirov, and later on the head of his secret service, Count Peter Tolstoy.

When Peter the Great died in 1725, his widow came to the throne as Catherine I, but Prince Alexander Menshikov, who had been Peter’s right-hand man, ran the show for her; he gave the palace to one of his minions, Alexei Volkov, the Chief Secretary to the Military Board. This was how the palace got the name “Palace of Boyar Volkov,” though Volkov was not a boyar (the appellation had fallen out of use by then) and owned it only about a year. Catherine I died in 1727, and for a little while Menshikov dominated her successor, Peter the Great’s grandson Peter II, who was only twelve years old. But Peter II detested Menshikov and soon got rid of him, exiling him to Siberia. After the fall of Menshikov Peter II apparently purged Volkov too, and gave his palace to Prince Grigori Dmitrievich Yusupov. Thereafter the palace remained in the hands of the Yusupov family until the Revolution of 1917.

The Yusupovs were the descendants of Tatar princes of the Nogai horde who had converted to Orthodox Christianity in the 17th century. They were quickly absorbed into the Russian aristocracy and were one of the richest families in Imperial Russia. By the end of the eighteenth century they owned 675,000 acres of land and 40,000 serfs. However, the male line ended in 1891 with the death of Nikolai Borisovich Yusupov, leaving his only daughter, the famous beauty Zinaida Nikolaevna (1861-1939), as heiress. She had married Count Felix Felixovich Sumarokov-Elston (1856-1928) in 1882. Count Felix became commander of the Imperial Guards Cavalry under Nicholas II, and later served as Governor-General of Moscow in 1914-15. After his father-in-law’s death, Tsar Alexander III granted Count Felix the title of Prince Yusupov and the right to pass it on to the couple’s heirs. Their older son, Nikolai, was killed in a duel in 1908; the younger, Felix Felixovich, married a niece of Tsar Nicholas II. He lived primarily in St. Petersburg, where in December 1916 his house became the scene of the murder of Rasputin – in which he participated. For this he was exiled to one of his estates. But after the Tsar’s abdication in February 1917, the Yusupovs went to the Crimea, then emigrated to the West. They lived in Paris, where Felix died in 1967.

In the early nineteenth century (1801-1803), Sergei Lvovich Pushkin, the father of the poet Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin (1799-1837) rented an apartment in the Volkov-Yusupov Palace, and Alexander himself lived there for a while.

In the 1890s Princess Zinaida Nikolaevna Yusupova undertook extensive restoration, including renewal of the stoves with genuine antique tiles.

After the Revolution, the Palace housed a series of Soviet institutions, of which the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL) had the longest tenure. But finally, in 2010, after a period of reconstruction, the Palace was reopened as one of the newest museums in Moscow, in one of its oldest buildings; thus its lavishly furnished interior chambers, restored to their former opulence, are now open to the public.

The Volkov-Yusupov Palace, according to its website, is one of the best-preserved residential buildings surviving from Muscovite Russia (15th-17th century). Most such structures, of which there are several dozen, survive only in fragments or else have been reconstructed and remodeled so often that they are now unrecognizable. By contrast, the Volkov-Yusupov Palace is preserved in its original form, with its vaulted ceilings and tiled stoves. There are a few later additions, such as chimneys, but these do not detract from the overall impression of a 17th-century Muscovite dwelling.

We continued to explore in the Chistye Prudy area for a little while before heading back to Moscow University. The surrounding neighborhood is said to be venerable and prestigious, and appeared to be relatively well-kept.

We encountered a few interesting items in our wanderings. For example, the building in the following photo was clearly of pre-revolutionary construction and quite likely had an impressive pedigree, but there was nothing on it in the way of identification.

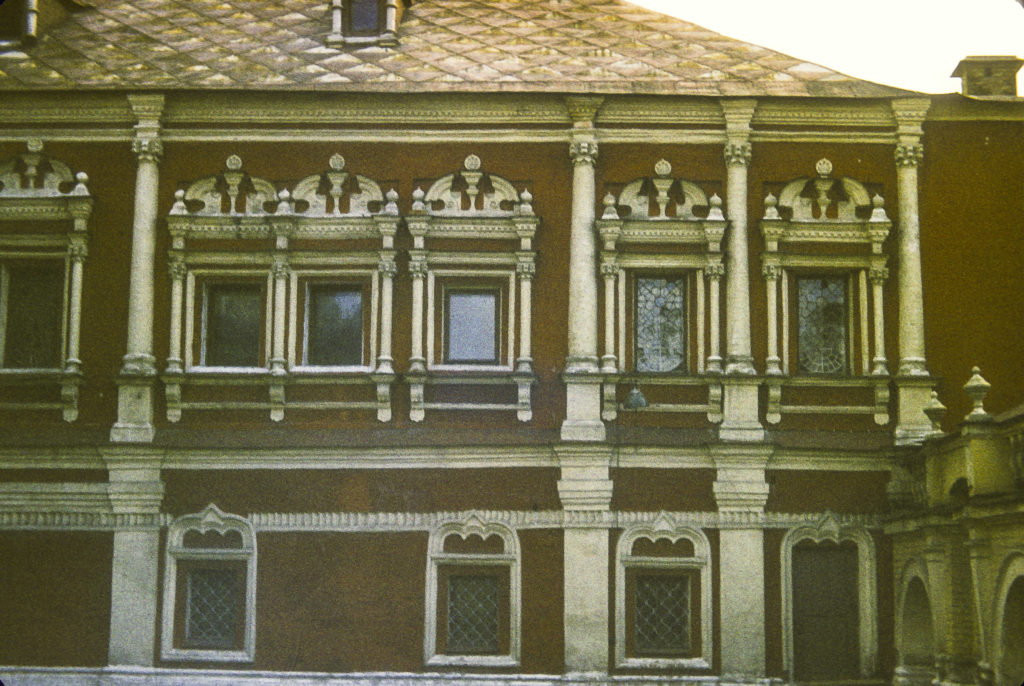

The same was true of the structure in the following few pictures. It appeared to be an apartment building with legal offices on the ground floow. Its salient feature was the elaborate and striking decoration around the second and third stories.

It would have been nice to find out who built this structure and especially who was responsible for the artistry, but there was nothing to provide any clues about it.

I imagine that the people who lived and worked here led comfortable lives by Soviet standards. I haven’t given up trying to find out more about it, and if nothing else, someday I hope to go back to Moscow and find out more about this and some of the other sights that remained “incognito” in 1973.