At Dave Winter’s recommendation, I booked a trip to the resort town of Nikko, about a 6-hour train trip north from Tokyo. It’s a slow local train, not the Shinkansen; the ride is leisurely and fun.

Nikko is a popular tourist destination and I can certainly understand why. It is a beautiful place, set in a forest in the mountains, with rivers, waterfalls and hot springs aplenty. It is also the site of the mausoleum of Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Tokugawa shogunate and one of the most significant figures in Japanese history.

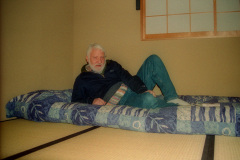

I arrived in Nikko in the late afternoon of a sunny April day and was immediately whisked off in a Toyota Camry to my lodging, a traditional Japanese inn (ryokan), driven by the hostess of the establishment. Everything in Japan is expensive these days, and has been since the 1970s, but the ryokan’s rates were very reasonable, the room was plain but comfortable, and the meals were fabulous. At dinnertime I met a German tourist who was hiking through Japan on a six-week vacation from his business – he owned a printing company in Cologne. Like most educated Germans, he spoke excellent English (sadly I’ve forgotten most of my German) and we had a fun evening drinking sake and swapping lies.

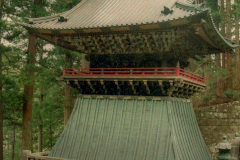

Next morning I began my explorations of the Nikko antiquities. There are three main shrines at Nikko – the Toshogu, the Rinnoji Temple and the Futarasan. The most elaborate, and the one I devoted most attention to, is the Toshogu, the mausoleum of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The Toshogu shrine was initially established in 1617, shortly after Ieyasu’s death, under his son and successor Hidetada. In the 1630s Ieyasu’s grandson Iemitsu greatly enlarged and elaborated it. One approaches the shrine via a stone Shinto ceremonial gate or torii, known as the Ishi-torii, at the end of a long flight of stone steps. Next to the Ishi-torii is a tall red pagoda, the Gojunoto, whose five stories each represent one of the five elements – earth, water, fire, wind and ether, in ascending order.

The main shrine area lies beyond the Omoteimon, a gate where one pays an entrance fee. Proceeding further, one encounters a series of ostentatious storage sheds and a stable for sacred horses; these feature elaborate woodcarvings by famous artists, which are among the most cherished treasures of Japan. Continuing up the hill, one passes under a copper torii to reach the famous Yomeimon gate, an incredibly ornate structure which is considered to be so beautiful that one can stare at it all day until sundown without ever getting tired of looking. Continuing on a somewhat circuitous route, one next comes to the Karamon, or Third Gate, also known as the Chinese Gate, leading to the main shrine building, which contains the praying hall (haiden) and main hall (honden). In the honden is an effigy of Tokugawa Ieyasu, somewhat idealized; in later life he was a very fat man, and by the time Will Adams met him in 1600 he was already far from the trim and robust horseman depicted by Clavell in Shogun – he already had difficulty mounting a horse by the time of Sekigahara – though he did enjoy falconry until the end of his life.

But this isn’t the end of the Toshugu odyssey. Next, one passes through the Sakashitamon Gate, which features a renowned carving of a sleeping cat, and continues on a tortuous flight of stone steps up the hill to still another torii leading to the Inner Shrine. Finally, after passing through the Inukimon Gate, one arrives at the mausoleum proper, containing Ieyasu’s tomb, a relatively simple but dignified funerary urn. Off to one side of the compound stands the Wish-Granting Tree, an ancient cedar which predates the mausoleum; generations of pilgrims have believed that if one prays facing the hollow of the tree, their wishes will be granted.

The second major establishment at Nikko, the Rinno-ji is a temple of the Buddhist Tendai sect, founded in 766 by a monk named Shodo Shonin. But it also administers the Taiyu-in Reibyo, which is a Shinto shrine and the mausoleum of the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu. This is indicative of the fusion between Buddhism and Shinto during the many centuries after Buddhism became established in Japan around 538 AD. In the main Rinnoji temple stand three statues of Buddhist “deities” (technically, Buddhism does not recognize any gods) who also represent the kami (spirits) of the three mountains of Nikko, who are also Shinto manifestations.

Rather than the temple itself, I focused on the mausoleum. Iemitsu, the third Tokugawa Shogun, Ieyasu’s grandson, became shogun in 1623, when his father Hidetada retired, but only became the de facto ruler in 1632, when Hidetada died. Iemitsu’s reign is noted for the suppression of Christianity and the “closing” of Japan to foreign contacts and influences. As early as the 1590s Japan’s rulers had issued edicts outlawing Christianity, but the these had only been sporadically and half-heartedly enforced; Iemitsu’s regime began a systematic effort not only to suppress Christianity but to exclude Westerners and Western influences in general. This culminated in the Sakoku Edicts of 1635, which forbade Japanese from travelling abroad or Westerners from settling in Japan, under penalty of death; prohibited the Christian religion; and limited trade contacts to one Dutch ship per year, restricted to the island of Deshima at Nagasaki. Thenceforth known or suspected Christians were required to demonstrate their renunciation of the faith by stamping on pictures of Jesus or Mary. Thousands who refused to do so were executed, often by crucifixion. These policies continued to be enforced until 1858, when the Americans compelled the by-then tottering shogunate, under threat of force, to open up the country to trade with Western powers.

The Nikko shrine complex is quite large, and, well, complex, and I had only a day to see it all; after traversing Toshogu I had only a limited time to explore Rinnoji and Futarasan. The latter, especially, is somewhat dispersed and vaguely defined as to extent, and I wasn’t able to reach all of its outlying sites. Here I have included in the gallery, in addition to the known Futarasan sites I visited, items that were probably not associated with Futarasan but which I could not classify with either Toshogu or Rinnoji.

Futarasan was founded in 767 by the same Buddhist monk who founded the Rinnoji Temple. The main shrine is located to the west of Toshogu, but for lack of time I bypassed that in favor of the Taiyu-in Reibyo, Iemitsu’s mausoleum, which is located nearby. I did, however, manage to see and photograph some of the most spectacular outlying Futarasan sights, notably the Kegon Falls and the Sacred Bridge.