Once we managed to get past the uncongenial guardian of the Triton Gate, Pena Palace revealed a myriad of new wonders. We were able to get close-up to the towers, turrets and terraces we had glimpsed from the park, and to view from above some of the marvels we had seen on the way up.

Pena Palace has a lot of towers, the tallest and most imposing of which is the Clock Tower, dating from 1843. It rises above the Queen’s Terrace, which can be reached by a steep climb up a flight of stairs, and provides some of the best views of the surrounding area. Among the other towers, my favorite was one which I don’t know the name of, but which I call “Rapunzel’s Tower” because it reminded me of the Brothers Grimm fairy tale about the girl who is imprisoned by a witch in a tall tower and rescued by a handsome prince for whom she lets down her long hair so he can climb up to her window. The girl atop this tower didn’t have long hair, and the prince had to climb the stairs to rescue her, and she was a brunette whereas Rapunzel was a blonde, but I had fun with it anyway.

And here are some of the expansive views of the Lisbon area and the palace park that I captured with my 70-200mm telephoto lens from the ramparts of the castle.

The Queen’s Terrace also provided an excellent vantage point for viewing and photographing parts of the New Palace. One of its features is a large turret tower where Ferdinand II planned to construct bedrooms for himself and Queen Maria. However, the New Palace was not completed before Maria died in 1853 after giving birth to her eleventh child, a stillborn son, and Ferdinand remained in his old quarters in the former cloister.

A modern addition to the New Palace is a cafe occupying a section of the roof, with a superb view of the park and the countryside.

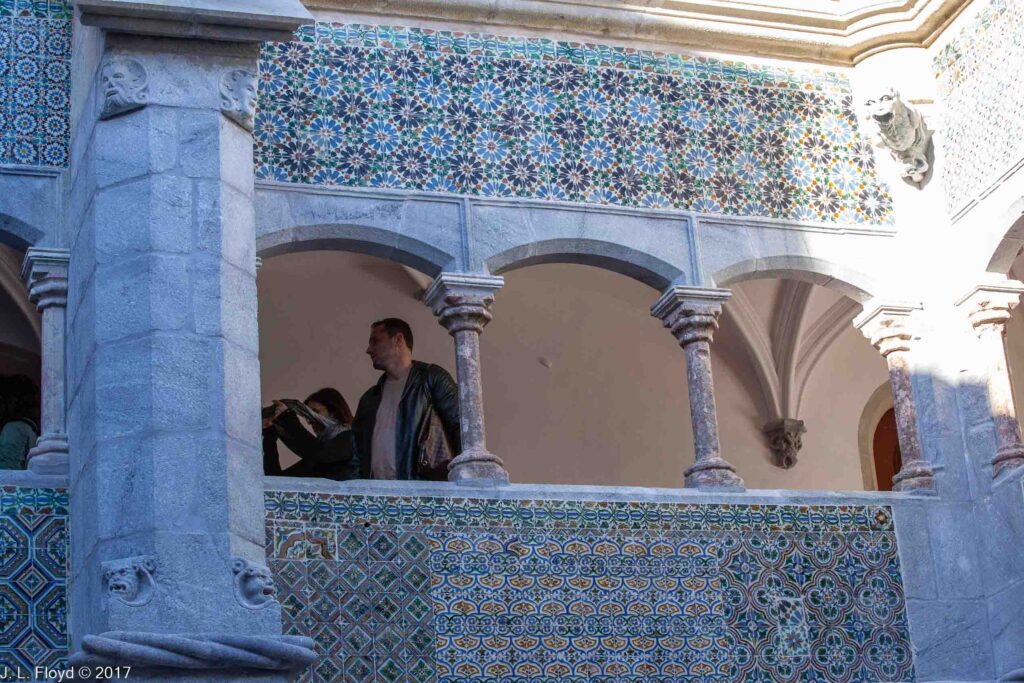

The cloister was the heart of the old monastery and is relatively small compared to, for example, that of the Jeronimos Monastery in Belem, since it was intended for occupation by only 18 monks. The monks’ cells became the quarters of the royal family after the conversion of the monastery into a palace.

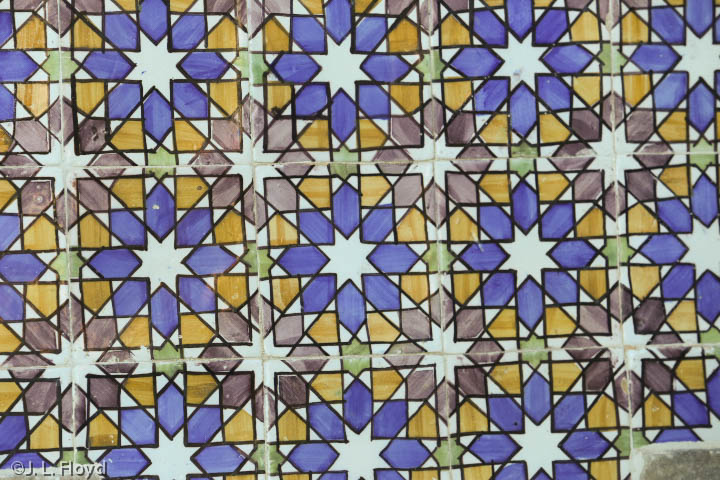

The galleries of the two-story cloister open up onto a central square patio through arches on both floors. The patio has an oyster shell like the one where the Triton is seated outside, but the Triton is missing here. The walls of the cloister are finished in gorgeous Hispano-Mudéjar tiles with geometric designs. Yes, I’m a sucker for ceramic tiles but these are incredible.

Ferdinand II was no longer King after the death of Queen Maria, but he was regent to his young son, the 16-year-old King Pedro V, until 1855. Pedro himself died of typhoid fever in 1861 and was succeeded by his brother Luis, who then ruled as Luis I until 1889. As King-Father, Ferdinand continued to carry some clout, and he occupied Pena Palace until his own death. In his later years, in defiance of the conventions of the Victorian era, he shared his chambers with his mistress, the Swiss-American actress Elisa Hensler, whom he eventually married (1869). To make the union seem more respectable, Ferdinand’s cousin, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg, bestowed upon Elisa the title of Countess of Edla. When Ferdinand died in 1885, he left Pena Palace and its grounds to her. She sold it to King Luis, and the royal family made extensive use of it, especially after Luis’ son Carlos became King on his father’s death in 1889.

Whereas Ferdinand II had occupied the upper floor of the cloister, Carlos I moved into the relatively modest quarters on the ground floor and left his wife Amelia, a French princess, to occupy the more regal apartments above. But he made one significant innovation: in accordance with the improving standards of hygiene in the late 19th century, he turned one of the rooms adjoining his bedroom into a bathroom. He also decorated his office with racy paintings of nymphs and fauns. There is a painting of an ethereally beautiful nude woman in the royal quarters, but I was unable to obtain any information on its provenance, who painted it and for whom, or whom it was supposed to represent; I doubt whether it was a painting of the Countess of Edla.

Queen Amelia’s quarters included, in addition to the bedroom, an office and a tea room, where she would sip her tea in the morning and receive her personal visitors. The furniture in these rooms, some of it remaining from the days of the Countess of Edla, is quite opulent.

What had been the monks’ refectory was converted into the royal dining room. It retains the elegant 16th century Manueline-style vaulted ceiling with ribbing, but the tiles on the walls and the elegant oak furniture are 19th-century in origin. The table was set for twelve and a sumptuous meal was in prospect; unfortunately we couldn’t stay for dinner since we had other plans.

The kitchen, surprisingly, is huge, the largest room in the palace except for the Noble Hall. It was evidently intended to provide sumptuous meals not only for the royal dining room but also for formal banquets in the reception rooms. All the pots and pans are imprinted with the monogram of Ferdinand II, a tactic for deterring theft.

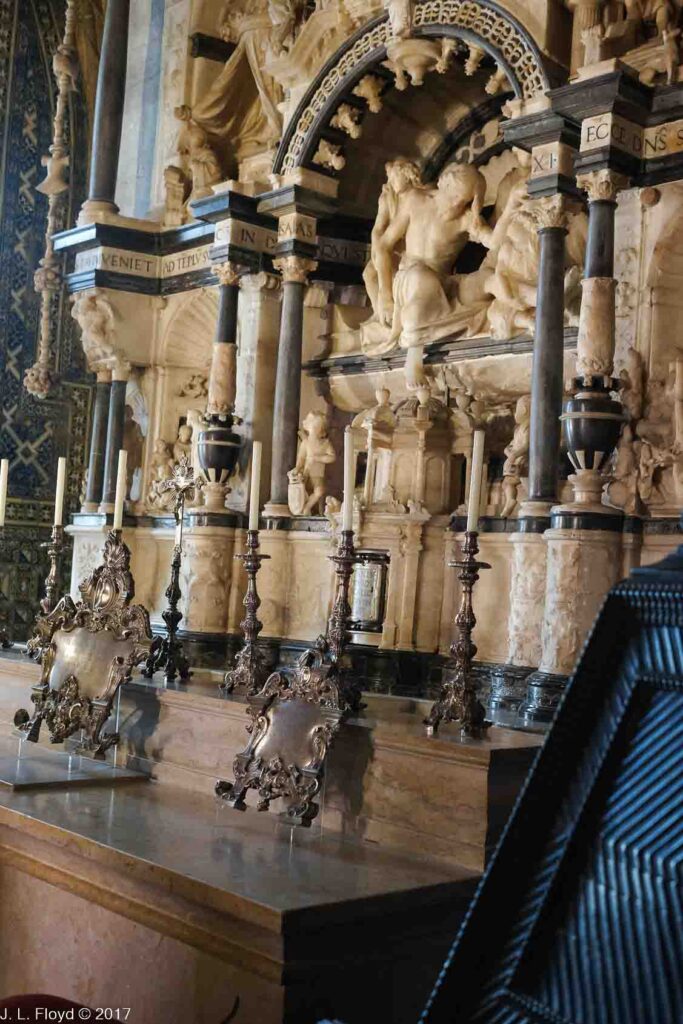

The Palace Chapel, next to the Dining Room, had been the Monastery Church of Our Lady of Pena prior to 1834, and Ferdinand II wisely left it mostly unchanged. It has the same type of ribbed vaulted ceiling as the Dining Room. It dates from the reign of King João (John) III (successor of Manuel I), who in 1528 commissioned Nicolas de Chanterenne, or Chantereine, a French sculptor and architect, to create the main altar retable. A retable (I had to look this up, since I’m not familiar with the terminology of ecclesiastical architecture) is a structure placed on or immediately behind and above the altar or communion table of a church – another word for it is “altarpiece.” Retables can be simple or complex. The one in the Pena Palace Chapel is an elaborate, exquisitely carved work in alabaster and limestone quarried from Sintra. By 1528 Chanterenne had already done extensive and masterful work in Spain and Portugal, including some of the finest sculpture of the Jerónimos Monastery in Belém; in 1519 King Manuel I had appointed him as his personal sculptor, and King João III continued to heap honors upon him. De Chanterenne worked on the monastery altarpiece from 1829 to 1832, and it is widely considered his greatest masterpiece. After completing it, he migrated with the King’s court to Évora, where he continued to live and work until his death in 1551.

As far as I can tell, the only significant change made Ferdinand II made to the chapel was to add a new stained glass window in 1841. Commissioned from a German firm, Kellner of Nuremberg, it depicts Vasco da Gama kneeling before King Manuel I after returning from the Indies. Manuel is said to have spotted da Gama’s ship sailing back into Lisbon Harbor from the monastery mountaintop in Sintra.

In the New Palace, Ferdinand II planned to inaugurate a great reception hall for ambassadors and other dignitaries, but the end of his kingship in 1853 put paid to that idea, and the chamber was set up as a billiard room instead. However, it is now known as the Noble Hall, or Great Hall, and has an appearance more in keeping with its original purpose. An elaborate 72-candle neo-rococo chandelier hangs from the ceiling, sumptuous sofas and tables line the walls, vases and china from Ferdinand’s porcelain collection are found throughout, and light enters the room through his more of his prized German stained-glass windows. The overall design is meant to be Arabesque, and four statues of Turkish janissaries stand in the room, one in each corner.

Adjacent to the Noble Hall in the New Palace is the Stag Room. This, of course, is where Ferdinand intended to screen his stag films. Again, though, things did not turn out as planned. For one thing, film had not been invented yet. So, being a devotee of King Arthur romances, he planned to have a Round Table placed around a central pillar, with suits of medieval knightly armor against the walls; swords and spears, crossbows, stuffed heads of stags and boars would be hung on the walls, in which his favorite heraldic stained glass windows would be installed; and sumptuous banquets for the King and his associates, supplied from the palace’s great kitchen, would be held there. But even this didn’t work out. According to some sources, the Round Table was duly provided, but when we were there, we saw only the central pillar and a few stag heads, but no table, round or otherwise. (You can see what it was supposed to look like here.)