Looking back, I can hardly believe we managed to see and do so much in one day – to see Lisbon’s King Edward VII Park, Belem, Jeronimos Monastery and Rossio Square in the morning, then Sintra and Pena Palace in the afternoon. Surely it must have taken two days to see all these sights! But no, the date-time stamps on the photos don’t lie; we did them all on November 5, 2017.

Sintra was an optional excursion on our Go-Ahead tour, but it was not optional for us; we had to see it. The previous year, on a visit to Bend, Chuck and Elouise Mattox had taken us to the Cafe Sintra in Bend, and introduced us to the owners, who were in fact from Sintra; and having learned something about the place, there was no way Sandie and I could not take advantage of an opportunity to go there.

Because Sintra is one of the most magical places on Earth. It is located in the mountains up above Lisbon, and commands marvelous views of the countryside all round. The town of Sintra is itself quite charming, but the major draw for tourists like us – 3.2 million of whom visited the area in 2017 – is the area’s castles and palaces. The major ones are the medieval Castle of the Moors (Castelo dos Mouros), the Portuguese Renaissance Sintra National Palace, and Pena National Palace. We visited only the last of these. I wish we could have seen the others, and I want to go back again and do so; but we would have needed more than one afternoon, or one day, to do that; I am grateful for having been allotted one afternoon of my life to see Pena.

Pena Palace (Palácio da Pena) is a bit reminiscent of Sleeping Beauty’s Castle in Disneyland, but that is only a pale shadow of Pena. The closest analogue I can think of is Neuschwanstein, the fairy-tale residence of the mad king Ludwig II of Bavaria. I’ve never been to Neuschwanstein (it’s on my bucket list), but Pena predates Neuschwanstein by several decades.

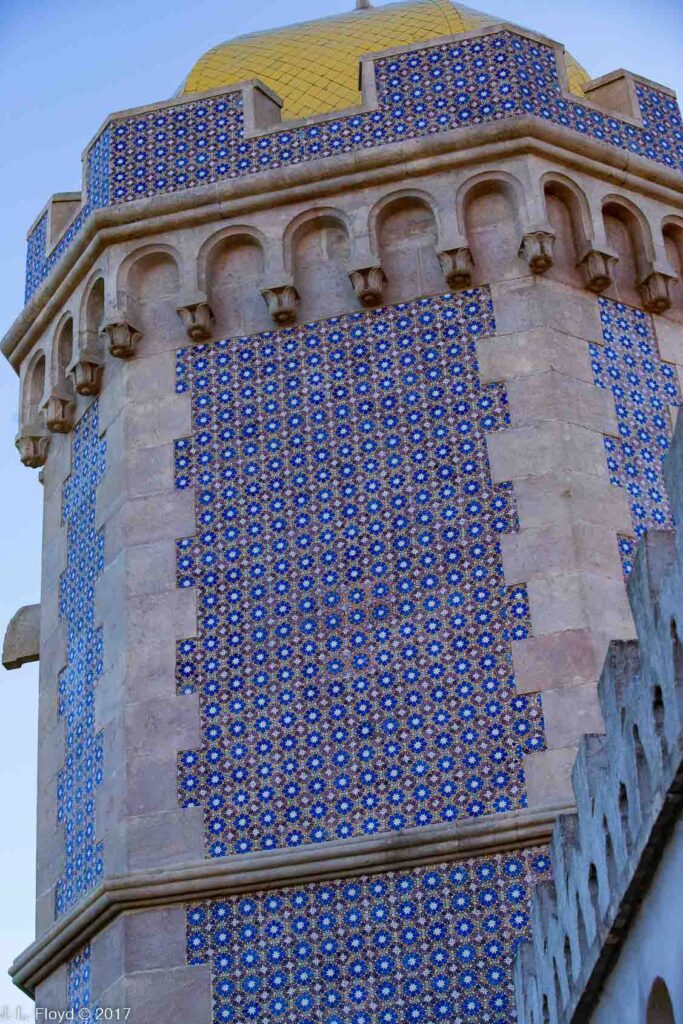

In 1836 the reigning Queen of Portugal, Maria II, married a German prince, Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg. According to Portuguese law, a reigning queen’s consort could only become King after the birth of an heir, which occurred in 1837. In 1838 Ferdinand, now King Ferdinand II, acquired an old monastery, originally built by Manuel I in 1511, on the hill above the town of Sintra. It had belonged to the Hieronymites, the same order that Manuel had selected to manage the monastery in Belem, but it had been deserted since 1834, when the government had dissolved the religious orders in Portugal. Ferdinand was enchanted with the place and set about refurbishing it as a summer residence for the royal family, but soon he turned it into a project for a whole new palace, conceived in the spirit of 19th-century Romanticism. He hired a German architect, Wilhelm Ludwig von Eschwege, an aficionado of Rhine castles, to do the design, but himself took an active part in the work, introducing medieval, Islamic and Renaissance features and borrowing heavily from Manueline motifs.

The designers preserved as much of the original monastery as possible, including the cloisters, the dining room, the sacristy, and the chapel. To this they added the Queen’s Terrace on the southern end of the east wing, and a new clock tower. But then they added another entire wing, called the New Palace, yellow in color, contrasting with the Old Palace, which is mostly red. They also created a vast park surrounding the palace. You cannot go directly to the palace entrance; you have to debark from your bus at the entrance to the park and walk or take a shuttle tram the rest of the way to the palace itself. We took the tram.

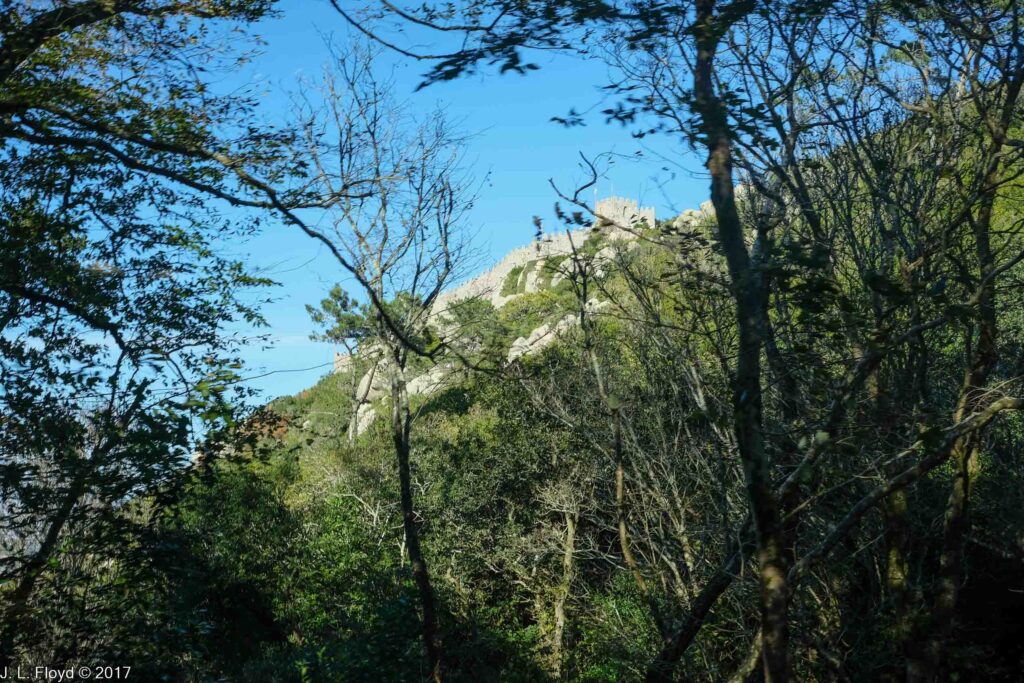

Even the tram does not take you all the way to the palace, but stops in a glade a little way off, providing the unexpected advantage of being able to obtain great views of the palace while walking the short distance to the gates.

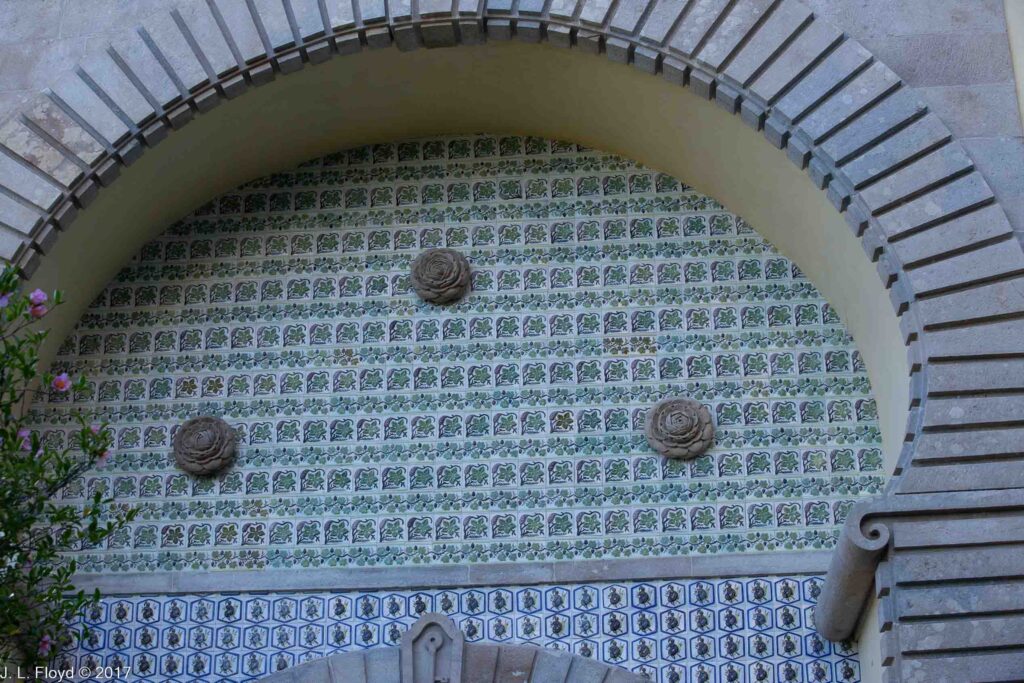

The first gateway opening into the palace complex is called the Door of Alhambra, or Alhambra Gate, so called because its design is said to have been inspired by the Gate of Justice in the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. Like the Gate of Justice, it features a double horseshoe-shaped Arabesque arch, Moorish tiles and Islamic symbols, in addition to elegant ceramic tiles. On the keystone of the arch is a carving of a human hand, the symbolism of which I’m still trying to ascertain. I particularly enjoyed the gargoyles in the shape of crocodiles which protrude from the corners of the arch. I call them “crocagoyles.” On top of the gate is a terrace with a walkway; tourists stroll casually along the terrace, oblivious to the threatening crocagoyles below.

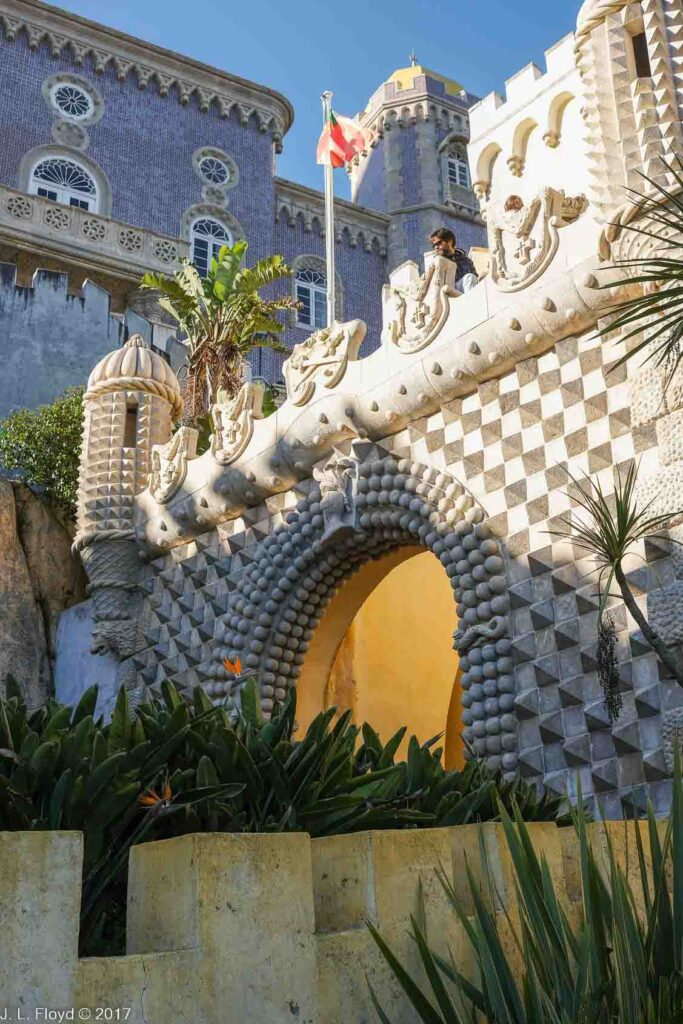

After passing through the Alhambra Gate, we found ourselves in the Coach House Terrace, where visitors to the Palace would have alighted from their horse-drawn coaches in days of yore. There we made a 180 degree turn and proceeded up a ramp to the Monumental Gate, which was apparently designed to emulate a Renaissance castle gatehouse. It has been disparaged as “a somewhat ridiculous looking fortified portal” executed in a “mishmash of styles,” but I thought it perfectly suited the fantasy-castle setting. Diamond spikes front the archway, and two cylindrical turrets called “bartizans,” ostensibly designed to function as sentry boxes, are perched on the top corners, with five coats of arms between them. Going under the rounded archway, we crossed a fake drawbridge leading into the entrance tunnel and the residential wings of the Palace.

At this point we emerged onto a terrace fronting the central section of the palace, which consists of the restored monastery with its neo-Manueline facade.

Here we encountered what I consider the single most striking feature of Pena Palace, an absolutely bizarre, idiosyncratic, and delightful creation, the Triton Arch or Triton Gate. Looking at the many pictures Sandie and I shot of it from various angles, I cannot cease to be amazed that anyone could conceive such an outlandish chef-d’oeuvre.

In Greek mythology, the Triton was a minor sea god, a son of Poseidon and Amphitrite, usually depicted as having the upper parts of a man with a fish’s tail, and holding a trumpet made from a conch shell. The Triton at Pena Palace does not hold a trumpet. He is seated on an oyster shell on the wall beneath a bay window. A tree or vine appears to be growing out of his head, with a profusion of branches and leaves extending up to enfold the window above. Instead of a trumpet he holds two branches of the tree on either side. He does not look happy, but then I wouldn’t be happy either, if I had to sit on an oyster shell holding up a tree growing out of my head FOREVER. He looks down upon the terrace with a snarling, menacing, utterly hostile gaze, as if warning visitors away. But he did not deter us from entering the palace under the arch below.

In the course of researching the myriad features of Pena Palace, I’ve come across a few disparaging descriptions. One critic in particular characterized it as “a heavy handed mish mash of different architectural styles….looks like several castles smooshed together…a schizophrenic whirlwind of onion domes, turrets, crenellation, and fanciful sneering gargoyles.” Regarding the interior, the same reviewer, among others, advised skipping it: “Don’t let anyone tell you it’s a “must do.” It’s not….Like the outside, none of it really matches or is in a cohesive style. It’s rather amazing that someone wanted it all under the same roof.”

There’s some truth in this; the palace is indeed a manic hodge-podge of disparate and sometimes incompatible styles; but to me that’s part of its charm. I don’t demand coherence when it comes to architecture. Palaces built over the centuries, like the Alhambra in Spain (as we’ll see when we get there), often acquire various and sometimes clashing constructions. King Ferdinand II, who had Pena built over the course of a decade or two, could have striven for unity and coherence, but the result would have been less remarkable and exciting, and most likely pedestrian and boring. There are plenty of other nineteenth-century European palaces where one can find consistency, conformity and adherence to sometimes sterile conventions of design. I like Pena Palace as it is – a wild romp of the imagination, a free exercise of creative energy. It’s a nineteenth-century precursor of Disneyland, where someone’s wildest dreams became reality, and in my view it beats its descendant hands-down.

And we didn’t skip the interior, which we found just as fascinating as the exterior. In the next post, I’ll deal with that.