The Monarch Queen was unable to make it to Regensburg because the water in the Danube was too low for navigation; instead she had to dock at Vilshofen an der Donau, about 100 kilometers downstream, not far west of Passau. A bus came to pick us up and take us to Regensburg.

The bus took us through a lot of pretty Bavarian countryside. We saw lots and lots of verdant fields and prosperous-looking farmhouses, several charming little towns whose names I forget, with their picturesque churches. We also saw a few things which had not been there during my previous visit to Bavaria in 1964: solar panels and electricity-generating windmills.

As we neared Regensburg, we caught a glimpse of a neo-classical building sitting on a hill on the north bank of the Danube. This turned out to be the Walhalla, a memorial named after Valhalla, the headquarters of the Norse pagan pantheon. It was conceived in 1807 by then Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria as a means of fostering German unification by reminding Germans of the great figures of German history and their achievements. Unlike the mythological Norse Valhalla, which was reserved for warriors slain in battle, Ludwig intended his Walhalla to honor persons of high achievement in various fields – artists, musicians, scientists, clerics, poets, philosophers, etc. Women as well as men were to be included. After Ludwig succeeded to the Bavarian throne in 1825, he commissioned the building of Walhalla modelled on the Parthenon in Athens. It was opened in 1842.

The monument was little visited until 1889, when a private narrow-gauge railway called the Walhallabahn was opened to carry passengers the 8.9 kilometers between Regensburg and Donaustauf, where Walhalla is located. (The railroad was extended in 1903 to the larger town of Wörth an der Donau, 14.5 kilometers farther.) The Walhallabahn continued to carry passengers between Regensburg and Walhalla until 1960, when service was discontinued.

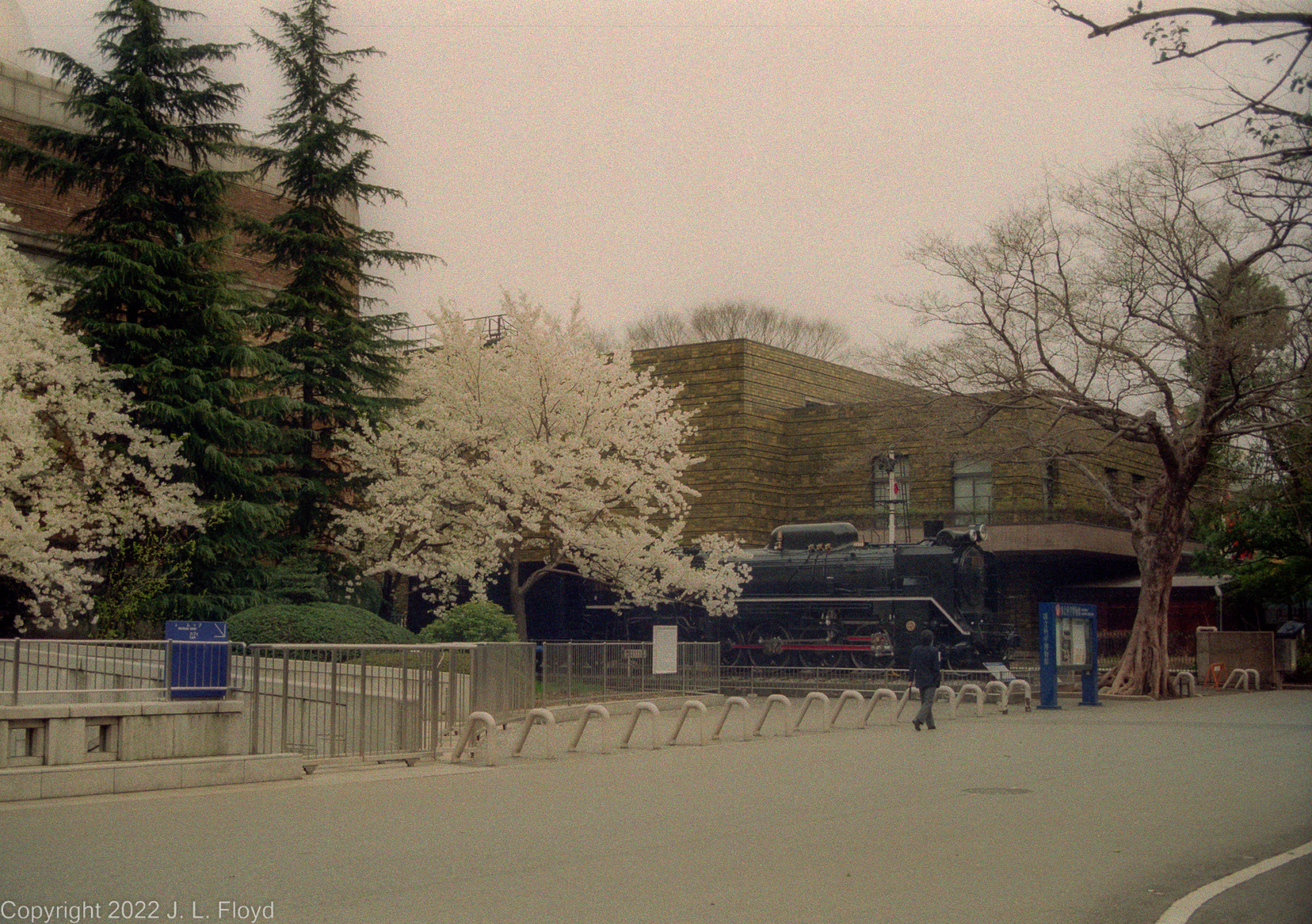

When we arrived in Regensburg, our tour bus deposited us at the edge of Stadtamhof, a district which was incorporated in Regensburg only in 1924. The bus terminal also turned out to be the open-air Museum of the Walhallabahn, featuring Locomotive #99-253, built in 1908 and retired in 1960, as the primary exhibit. Here we met our local guide, who turned out to have the improbable name of Paco Garcia. He informed us that he was from Sacramento, California, but had been living in Regensburg for about 20 years.

As it reaches Regensburg, flowing from west to east, just before its confluence with the Regen River, which flows in from the north, the Danube splits into three channels. The Stadtamhof district is actually an island bounded by branches of the Danube to the north and south. The north branch of the river is part of the Rhine-Main-Danube canal, a navigable waterway. The middle branch separates Stadtamhof from another island, Wöhrde, and the south branch divides Wöhrde from the Inner City (or Old City) of Regensburg.

Stadtamhof is crossed from north to south (and vice versa) by a wide boulevard, in contrast with the Inner City of Regensburg to the south, where the streets are all quite narrow. It takes only a few minutes to walk to the south side; just before reaching it we passed an institution whose spiffy appearance belies its age. This was St. Katherinenspital, founded in 1213 as a hospital for the poor. It became one of the earliest community hospitals in the Holy Roman Empire.

In medieval times, if you were rich and became ill, the doctor would come to your home to treat you. If you were poor, your only recourse would be to go to a hospital; most of these were maintained by monasteries and other religious foundations. St. Katherine’s was founded by the Bishop of Regensburg, Conrad IV, in a joint venture with the citizens of Regensburg, who were expected to provide financing for the establishment. But this was at a time when the city of Regensburg was undergoing a transition from a dominion of the Duke of Bavaria to a Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire, and the political situation was highly unstable. Eventually the citizens of Regensburg successfully asserted their independence from Bavaria, except for Stadtamhof, which remained under Bavarian rule. The status of St. Katherine’s remained unclear, however, and in dispute. I suspect this was because the Bavarians would not have been overjoyed about footing the bill for the hospital, which existed mainly for the benefit of the citizens of Regensburg; and for their part, the Regensburgers were wary about footing the bills for a property over which they had no supervision. Thus the admininstration and funding of the hospital underwent many ad hoc changes until the 19th century, when both the Kingdom of Bavaria and the city of Regensburg were incorporated into a unified Germany. Even then not all matters were settled, and St. Katherine’s continued to undergo not only administrative but also functional changes: today it is no longer a full-service hospital but a retirement and nursing home for the elderly.

Passing by St. Katherinenspital, we embarked on the Steinerne Brücke, the Old Stone Bridge that connects Stadhamhof with the main part of Regensburg. Built in the mid-12th century, it is considered a masterpiece of medieval engineering. For 800 years it was the only bridge across the Danube at Regensburg. It remains one of the two major emblems of the city, along with the cathedral. The bridge consists of 16 stone arches and is supported by piers on the islands and in the river itself. Stone abutments were constructed to protect the piers from being undermined by the river currents. The Regensburg Stone Bridge became a model for a number of other medieval bridges, including London Bridge (the one which is now in Arizona, not the Tower Bridge which remains in London).

The Stone Bridge has long been an impediment to navigation on the river, because of the narrow passages between the abutments, the low clearances of the arches, and the strong currents it causes downstream. Formerly vessels going upstream had to be towed past the bridge. Nowadays, only small recreational and excursion boats use this stretch of the Danube; larger vessels bypass it by diverting to the canal north of Stadtamhof, which we had seen upon our arrival there. I don’t know where the Monarch Queen would have docked if it had been able to come all the way to Regensburg, but it would certainly not have passed under the Stone Bridge.

No trolls popped up from under the stone bridge to challenge our crossing, but about halfway we encountered something similar: a stone figure of a man, seated on top of the pointed roof of a miniature toll house, facing south, and shielding his eyes with his right hand. This was the famous Bruckmandl, or Bridge Man, about whom a number of legends circulate. My favorite is that he is the builder of the bridge, who supposedly made a wager with the builder of the cathedral as to who would finish first, and is looking toward the cathedral site to the south in apprehension that the cathedral builder was making alarmingly swift progress. To ensure that he won, the bridge builder then made a pact with the Devil. The payment for Satan’s help would be the souls of the persons associated with the first eight feet that crossed the bridge. The builder cheated Satan by sending a rooster, a hen and a dog across the bridge first. Satan, in his rage at being fooled, attempted to destroy the bridge but failed, only succeeding in bending it (the bridge does have a bend in the middle). In fact, the legend has no substance because the cathedral was built a century later than the bridge, but it’s a fun story.

At the south end of the Stone Bridge is the Bridge Tower (Bruckturm), built around 1300. It has a clock, added in 1648, and an arch through which one enters the Old City. It is in the middle of a cluster of buildings which includes the Salzstadel (salt warehouse) on its left (east) and the former toll house (originally a chapel) on its right.

To the east of the Salzstadel is the Historische Wurstküche, Historic Sausage Kitchen, about which more later, and a little further down the riverbank is the Anlegestelle Donauschifffahrt, or Danube Shipping Wharf, which appears to be the most likely place where river cruise ships such as the Monarch Queen tie up when water levels are high enough for them to come to Regensburg. (They would then turn around and go back rather than continuing west under the Stone Bridge.) There was in fact a river cruise boat tied up at the wharf, but it was smaller than the Monarch Queen. While we were crossing the bridge I saw (and photographed) a very odd-looking craft, long and narrow and looking a bit like a Venetian gondola, with two very long poles or oars (they had flat blades on the ends) hanging on the stern. The boat pushed off the wharf, then shot under the bridge and off to the west. My guess is that it was an excursion boat of some sort, and the long poles or oars were there to provide a way of pushing off sand banks or away from navigational hazards, perhaps even to paddle the boat if the motor should fail. Later I found out that there are day cruises to the Walhalla memorial in Donaustauf which leave from the same wharf.

Passing under the Bridge Tower arch, we entered the Old City on Brückstrasse, Bridge Street, where the first house on the right had a prominent round tower on the corner. I had of course seen such towers on residential buildings in Germany and Austria before, but they seemed ubiquitous in Regensburg; I saw at least one of them on almost every street corner we passed in the Old City.

Regensburg is a very old city and was important even in Roman times. In 179 AD Emperor Marcus Aurelius had a major new camp called Castra Regina built at what is today the Old City of Regensburg. All that remains of that camp today are the ruins of the Porta Praetoria, which was the main gate of the fortified camp: a pile of stone blocks that have been cleverly integrated into what used to be the Bishop of Regensburg’s palace. Some of the stone blocks constitute part of the lower section of a corner tower, and others have been used to form an archway for a portal nearby.

From the Porta Praetoria, our guide led us west toward the city center. On the way we passed the Goliath House, a “city castle” built in 1260 for a patrician family. It is noteworthy chiefly for a huge mural of the battle between David and Goliath on the street side of the building. The painting, created in 1573 by Melchior Bocksberger, must have been refreshed, renewed and repainted several times over the centuries since it looks like it was done yesterday. Our guide informed us that Oscar Schindler, of Schindler’s List fame, had lived in the Goliath House for a while after World War II before emigrating to Argentina.

As we continued west along Goliathstrasse, I caught sight of a high tower with Gothic windows on a side street and paused to take a picture. This turned out to be the Baumburger Turm, a 7-story tower constructed during the 13th century. During that era there was competition among the patrician merchant families of the city as to who could build the highest and most grandiose family residence. The Baumburger Turm, at 28 meters (92 feet) high, is only the second highest — the Goldener Turm (Golden Tower) on Wahlenstrasse, which we would see later, tops it at 50 meters or 164 feet — but it is considered to be the most beautiful of the 20 surviving towers. It was built in 1270 by the Ingolstetters, one of the great patrician families of the time, but in the 14th century it was acquired by the Baumburgers, and their name stuck.

Emerging from Goliath Street, we found ourselves in the Kohlmarkt, a square which in days of yore had been the place where charcoal, a very important commodity for blacksmiths and everyone else, was sold. As far as I could tell, charcoal is no longer being sold there; instead it is a pleasant area to relax and enjoy an ice cream or coffee at Crema Gelato or lunch at one of the several cafés located there. It is also the site of a fountain called the Lebensbrunnen, or Fountain of Life. This is not part of the historical ambience of the square but a modern implant, in the form of a granite cup with melting sides, such that it gives the appearance of a grotto. Water spouts below the cup fill a basin which in turn spills into four smaller basins around the base. The fountain is the work of sculptor Günter Mauermann and was installed in 1985 as part of a city beautification project.

Kohlenmarkt leads right into the Rathausplatz, the seat of city government in medieval and early modern times. There is located the Altes Rathaus, the Old City Hall, which consists of several separate structures, built at different times in different styles. The oldest is the 55-meter (184 feet) tall Council Tower, built in the middle of the 13th century in the style of the patrician family towers such as the Baumburger Turm. Next came the Reichsaale building, constructed around 1320, to the west of the Council Tower. It was originally intended as a free-standing building for hosting municipal assembly and festival hall, but it soon found another use. The second story was originally accessed only via an outside staircase, but this was remedied in the 15th century by the construction of the Portal building, which provided inside access to the second floor and in 1564 was extended to connect to the Council Tower as well. Also in 1564 a new Baroque wing was added to the complex on the east side of the Council Tower.

But this was not the end of the story. In the second half of the 16th century Regensburg became the preferred meeting place of the Reichstag (legislature) of the Holy Roman Empire. The city fathers felt an obligation to give the Rathaus complex an appearance commensurate with its importance. One way of doing so was by painting the buildings, and in 1575 the town council gave Melchior Bocksberger, the same artist who painted the mural on the Goliath House, a commission to do something similar for the Rathaus. Unlike the Goliath House murals, however, his paintings on the Rathaus buildings have long since vanished.

To the east of the Rathausplatz, on Kohlmarkt, another structure, called the Market Tower, had been standing for centuries. In 1706 it burned down, and a few years later, in 1721, a new southern extension of the Baroque wing of the Rathaus was built on its foundations. As well as municipal offices, this edifice now houses a restaurant called the Ratskeller.

The Imperial Diet, the Reichstag, met in the Reichsaale, which has an elaborate bay window on its western façade, where the Emperor appeared on occasion to make proclamations and receive the homage of the people. After 1594 the Reichstag met exclusively in Regensburg, which in effect became the co-capital of the Holy Roman Empire with Vienna, and after 1663 it became known as the Perpetual Reichstag because it was in permanent session, never dissolved. It was also never a real representative legislature, but in effect only a convocation of the Imperial Estates, i.e. the territorial and ecclesiastical princes and Imperial free cities, which meant in practice — at least in its later years — an assembly of the ambassadors of the constituent states of the Holy Roman Empire.

Directly across Rathausplatz from the Ratskeller we found the Café Prinzess, which claims to be the oldest coffeehouse in Germany, operating continuously since 1686. A bit skeptical of the claim, I did a little online research later on and found that the earliest coffeehouses in Germany were opened in Bremen and Hamburg in the 1670s — which would seem reasonable, since these cities are closer to the Atlantic and therefore would be more likely to be exposed to imports from the New World before inland locations such as Regensburg. Another coffeehouse was opened in Nuremberg in 1686, the same year as the Café Prinzess. So the Prinzess’ claim is perhaps legitimate, as long as one qualifies the area as South Germany rather than Germany in toto.

From the Altes Rathaus our guide led us south on Wahlenstrasse – “Election Street” – toward Neupfarrplatz (New Parish Square). The main attraction on Wahlenstrasse is the Goldener Turm (Golden Tower), the highest of the medieval family towers – not only in Regensburg, but the highest north of the Alps. Its construction was begun in 1250 by the Waller (or Woller, nobody seems to know for certain) family, but the upper stories were completed later, in the 14th century, and the pyramid roof around 1600. The name “Goldener Turm” has nothing to do with any material used in the construction of the tower, but rather with an inn by that name which existed there in the 17th century.

As I’ve already mentioned, the Market Tower on Kohlmarkt burned down in 1706. It had been serving as the city’s watchtower, and with its demise, the Golden Tower was pressed into service as its replacement. Various modifications were made to make it more accessible and comfortable for the guards manning the tower.

In 1985 the Golden Tower was renovated and given over to the local student union to serve as a student housing facility for the University of Regensburg. It has 43 apartments, most of them in shared-living arrangements where the occupants share a common kitchen and bathroom.

Our guide, Paco Garcia, showed us into the attractive courtyard of the Golden Tower, which is surrounded by Renaissance arcades on three sides and has a dogwood tree in one corner. Parking is available for bicycles in the courtyard, but cars are not allowed.

Resuming our progress on Wahlenstrasse, we continued south to Neupfarrplatz. It came as a surprise to me – not being an expert on German history – that Regensburg was a major center of the Protestant Reformation in Germany. I hadn’t known that by 1542 the town council was entirely Lutheran, and in that year the city officially adopted the reformed faith. Catholics were in the minority and were deprived of civic rights, though they were not driven out (that only happened to the Jews, in 1519). The Bishop of Regensburg maintained his seat, and the Catholic cathedral continued to operate, along with several abbeys. The Imperial Diet continued to meet in Regensburg. Emperor Charles V, a devout Catholic who was determined to roll back Protestantism in the Holy Roman Empire, continued to show up in Regensburg in the course of his official activities and sometimes stayed for extended periods.

Back in 1519, as I already noted, the good people of Regensburg had, in their immeasurable kindness and mercy, decided to drive out the Jews living there. Actually this sentiment had been accumulating for some time, and both the bishop and the town council had repeatedly applied to the Emperor to be allowed to expel the Jews, but Maximilian I, the Holy Roman Emperor at the time, had refused permission. In January 1519 Maximilian died, and a month later the Regensburg city council, taking advantage of the interregnum, took matters into its own hands. The Jews were given two weeks to leave the city. Their houses and their synagogue were razed to the ground. Meanwhile, plans had been drawn up to build a new church on the site of the synagogue, and construction began immediately, using rubble from the demolished Jewish buildings. At that time Regensburg was still Catholic, and the new church was to be named St. Mary’s. Then, in 1528, funds for the construction ran out and work had to be halted, leaving the church only partly complete. When Regensburg converted to Lutheranism in 1542, the city council decided to make the incomplete St. Mary’s the first Protestant church in town and renamed it the Neupfarrkirche, or New Parish Church. But it was not finally completed until 1860.

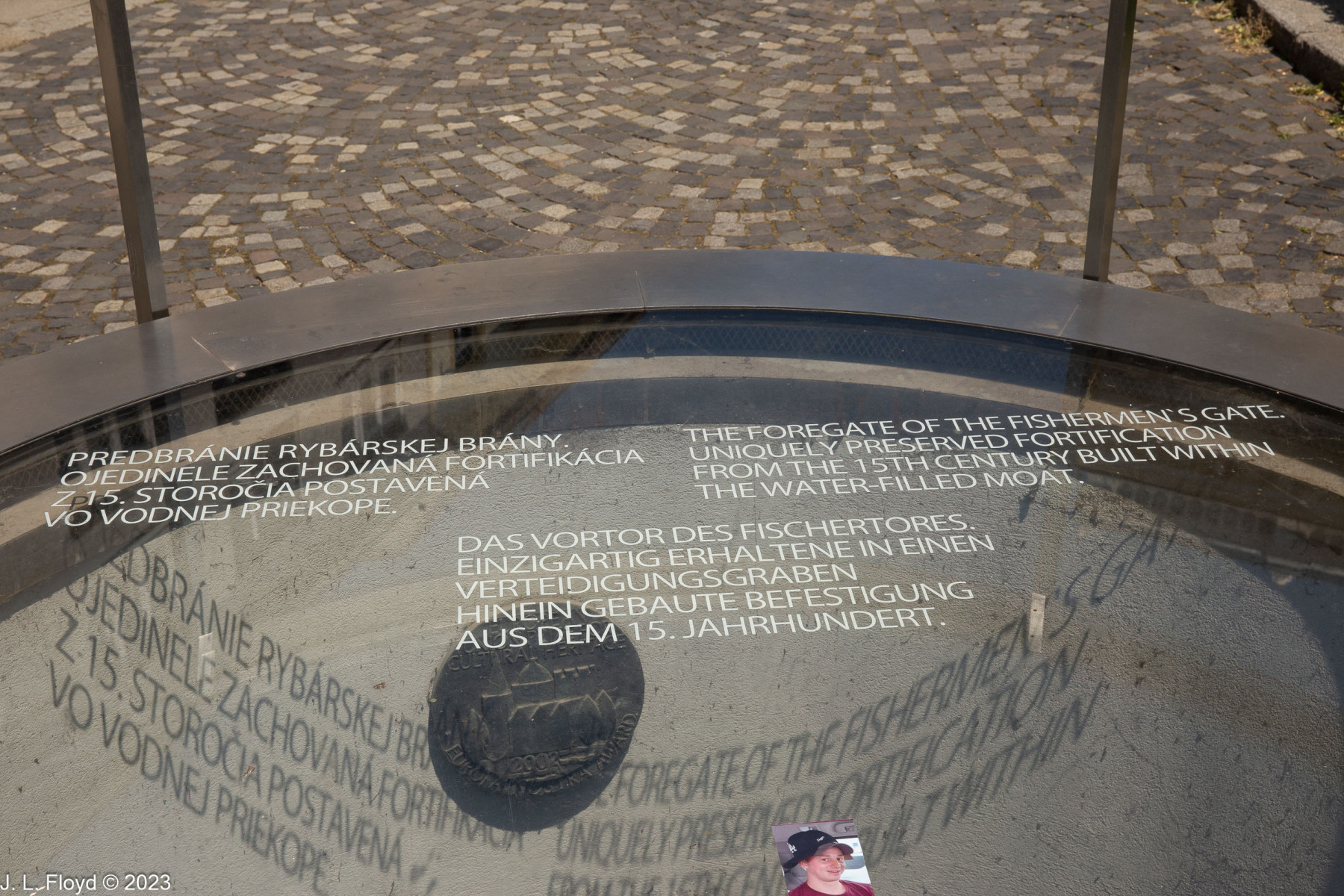

The Neupfarrplatz, which surrounds the Neupfarrkirche, is thus the old Jewish quarter of Regensburg. At its west end, where we came in from Wahlenstrasse, stands the elegant Baroque Reichsstadtbrunnen, or “Imperial City Fountain”, which dates from 1721. Between the fountain and the New Parish Church is the Synagogengrundriss, also known as the Misrach monument. In 1995-97 excavations were conducted which unearthed the remains of the old Jewish synagogue on Neupfarrplatz; a decade later, an Israeli artist named Dani Karavan created on that site a replica of the floor plan and foundation of the synagogue using white granite blocks.

In 1611, on the east side of Neupfarrplatz, a wooden structure called the Hauptwache (Main Guard Station) was built to house the town militia. This body was made up of citizen soldiers, although after 1663 the city hired mercenaries to fulfill their duties instead. These duties included maintaining order in the city, performing guard duty at the gates, and providing military contingents for Imperial forces in times of crisis as required, for example during the siege of Vienna by the Turks in 1683.

In 1820 the wooden Hauptwache was replaced by a stone building with a Tuscan portico, supported by eight columns made of green sandstone. In 1875 a second story was added to the house. After World War II, the building — by this time known as the Alte Wache (Old Guard House) — was used to house the city library, but in 1973 it was demolished to make way for a new indoor shopping mall, the Galeria Regensburg Neupfarrplatz. However, the façade was retained and incorporated into the new mall, and thus still may be seen today.

From Neupfarrplatz it was just a short walk northeast to Domplatz —Cathedral Square. The Gothic cathedral of Regensburg was begun in 1280, after the previous one burned down, at a time when the economic fortunes of the city were at their height. The design was grandiose – a French architect was hired for the purpose, so the cathedral was built in the French Gothic style. It is the only Gothic cathedral in Bavaria. Construction continued for over two centuries, but then Regensburg fell upon evil days; economic downturn, religious upheaval and civil unrest led to the cessation of work on the cathedral in 1520. Although a few additions and modifications were made during the next three centuries, it remained unfinished, and in particular the towers with their spires remained mere stumps, about half as high as planned. It was not until the 19th century that any further progress was made. Following the Napoleonic Wars, Regensburg was incorporated into the Kingdom of Bavaria, and its King, Ludwig I, started taking an interest in the cathedral. Ludwig commissioned a neo-Gothic renewal in the 1830s, and in the 1860s the cathedral was finally completed with the addition of the towers and spires. In honor of his patronage, an equestrian statue of King Ludwig erected in 1903 stands on the south side of the cathedral.

We did not see the inside of the cathedral because it was now time for lunch, and our luncheon spot was right next door to the Cathedral. It was the old bishop’s palace, now a 4-star hotel, the Bischofshof am Dom. It has an open-air restaurant, the Bischofshof Biergarten, in its courtyard, and there we enjoyed an excellent lunch of beer and sausages.

After lunch we were turned loose to wander about as we pleased, with the proviso that we wander back to the Walhallabahn Museum to reboard our bus by the appointed time. I chose to wander west on Goliathstrasse toward Keplerstrasse, a street named after a famous astronomer who had once lived there. Keplerstrasse is a block or two north of Goliathstrasse and to get there, I took a right turn at Zieroldsplatz, which runs along the east side of the Altes Rathaus. On Zieroldsplatz there is a statue of Don Juan of Austria, which I had seen from Goliathstrasse earlier, but now I had a chance to stop and get a better photo of it, which I did.

I would not have expected to see a monument to Don Juan of Austria in Regensburg or anywhere in Bavaria, because his career was associated almost entirely with Spain and not at all with Germany — except for his birthplace, which was Regensburg. It turns out that Emperor Charles V made his last visit to Regensburg in 1546, during the Schmalkaldic War, when he was attempting to subdue a league of unruly Protestant princes. He stayed at the Goldenes Kreuz (Gold Cross) Inn on Haidplatz, a favorite hostel for princely visitors, and while there had an affair with a woman named Barbara Blomberg. His wife, Isabella of Portugal, had died in 1539 and he had not remarried. Barbara, as the daughter of an artisan, was a commoner and would not have been considered eligible to marry royalty. The birth of Don Juan, which occurred on January 24, 1547, was kept a closely guarded secret. Charles V shortly left Regensburg and won an overwhelming victory over the Protestants at the Battle of Mühlberg in April 1547. Don Juan was taken to Valladolid, Spain, in 1554 to be raised by a Spanish noble family. He did not meet his father until just before Charles’ death in 1558. In his last will, Charles expressed an intention to have the boy take holy orders and pursue an ecclesiastical career.

Don Juan, it turned out, had other inclinations, which were toward a military vocation. He earned his spurs fighting pirates in the Mediterranean and then by suppressing the rebellion of the Moriscos in Spain in 1568-71. In 1571, he was made commander-in-chief of the armada of the Holy League, an alliance between King Philip II of Spain (Don Juan’s half-brother), the Pope and other Christian powers against the Turks. On October 7, 1571, the Christian forces met and annihilated a much larger Turkish fleet in the Battle of Lepanto, and Don Juan was hailed as a hero. A statue of him was sculpted and installed in Messina, Sicily, where the Christian fleet had sailed from. The statue in Regensburg was erected in 1978 and is an exact copy of the one in Messina.

Don Juan was less successful in his next major assignment. In 1576 Philip II sent him to quell the revolt of the Netherlands, which the king’s uncompromising religious policies had provoked. He was initially successful, winning a great victory over the Protestants in the Battle of Gembloux. But six months later he suffered a defeat at Rijmenam, and two months after that he contracted a fever (probably typhus) and died on October 1, 1578, at the age of 31. He is buried in the Escorial, Philip II’s monastery-palace near Madrid.

From Zieroldsplatz I continued north to Fischmarkt, which if one turns west becomes Keplerstrasse. At Keplerstrasse 5 I found the Keplergedächtnishaus, or Kepler Memorial House. I was a bit disappointed to learn that Kepler lived there for only a month in 1630. He lived most of his life, and did all his significant work, in Graz, Linz and Prague.

Kepler was born in 1571 in another Free Imperial City, Weil, in the German state of Württemburg, and attended the University of Tübingen, also in Württemburg. He wanted to become a minister (Protestant), but poverty, along with his skills at mathematics and astronomy, led to his taking a position as astronomer with a Lutheran school in Graz, the capital of the province of Styria in southern Austria, in 1594.

It was Kepler’s misfortune to live during the height of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, when the Habsburgs were undertaking a concerted effort to roll back the Protestant tide in Germany. Leading the charge was the Archduke Ferdinand, who became ruler of Inner Austria (Styria, Carinthia and Carniola) in 1597 and the next year expelled Protestant teachers and preachers from his domains. (He would eventually become Holy Roman Emperor in 1519.) By that time Kepler had made a name for himself and was able to land a job with the Imperial Court Astronomer, Tycho Brahe, in Prague. When Brahe died suddenly in 1601, Emperor Rudolf II immediately appointed Kepler to step into Brahe’s shoes. Rudolf was mostly interested in astrology – in those days astronomy and astrology were not distinct disciplines – and Kepler was required to cast horoscopes for the monarch. Nevertheless during his time in Prague he published some of his most significant works, including Astronomia Nova (1609), in which he set forth his laws of planetary motion, which asserted that planets orbited the sun in ellipses rather than circles.

Although Rudolph’s successor Matthias confirmed Kepler’s position as court astronomer after his predecessor’s death in 1612, the imperial treasury was empty and Kepler’s salary was not being paid. In the same year Kepler accepted a position in Linz as mathematician to the states of Upper Austria, without resigning as court astronomer. Kepler’s residence in Linz was not devoid of travail. Although he steadfastly refused to convert to Catholicism, his independent views on religion earned him the enmity of the Lutherans, who made what trouble they could for him. This included an accusation of witchcraft against Kepler’s mother, still living in Württemburg, and he had to take several months off work to defend her, in which he was successful. The Thirty Years’ War, which broke out in 1618, at times threatened to engulf Linz, which was besieged in 1626-28. Amidst all the chaos, Kepler’s patrons had other priorities than astronomy and failed to come up with the sums they had committed to pay. In 1830, Kepler decided to seek restitution from the Imperial Diet, and on October 8, 1830, he set out for Regensburg, where it was meeting. Worn out by the rigors of a long ride on horseback, he soon fell sick and died a month later, on November 15, at the age of 59, in the house he had rented, on the street that many years later was named after him.

I continued down Keplerstrasse a little way, then turned around and went back to Fischmarkt, taking photos as I went. There was much to see: elegant Baroque buildings with rounded corner towers and bay windows; upscale restaurants, cafés and pubs; a ceramics shop with exquisite wares; and two pretty fountains, the Fortitudobrunnen on Fischmarkt and the Wiedfangbrunnen at the corner of Goldene-Baren-Strasse and Am Wiedfang alley. The Fortitudo Fountain is supposedly part of a trio representing the cardinal civic virtues of Fortitude, Justice and Peacefulness. (I did not see either of the other two, assuming they still exist.) Fortitude is depicted as a figure of a youth standing on a dolphin, holding a fish in his left hand. The Wiedfangbrunnen is actually an old well, built in 1610 and renovated many times over the years, so that it looks almost like new. It is no longer used as a well, of course, and is blocked by a grating.

At Am Wiedfang I took a left and went north to the riverbank, with the aim of shooting some photos of the Stone Bridge from the side. I noticed that the closer I drew to the river, the more graffiti I saw, and when I reached the riverfront, the graffiti were ubiquitous. So I photographed the graffiti, too. I gather that graffiti are a common sight in European cities these days; I had seen them in Spain and Portugal in 2017, and in Vienna a few days earlier. Disregarding the graffiti, though, the south bank of the Danube in Regensburg has a nice long promenade, with stone benches where people can take a break.

By now it was time to return to the bus and say farewell to the marvellous medieval city of Regensburg. Before I crossed back over the Stone Bridge, I stopped by the Wurstküche. I didn’t have time or appetite to sample any of its famous sausages, but I did take a couple of pictures.

The Historic Sausage Kitchen of Regensburg began as the construction office for the Stone Bridge in 1136. When the bridge was finished in 1146 the little building was turned into a restaurant which served boiled meat. The customers were dockers, sailors, cathedral workers and other local people. Around 1800 the menu was changed to feature charcoal-grilled sausages. Currently it serves around 6,000 sausages per day. You can get them with sauerkraut and mustard; other dishes are available as well. The tiny restaurant only seats 35 people, but there is an outside dining area which can be used in fair weather.

The Regensburg Sausage Kitchen has been in business continuously for over 800 years, and claims to be “the oldest continuously open public restaurant in the world.” But the day before, I had been assured that St. Peter’s Stiftkulinarium in Salzburg was the oldest restaurant in the world, having been opened around 800. Which claim should I believe? Perhaps it depends on the wording. Maybe St. Peter’s was not continuously open during the entire period of its existence, or perhaps it was not public for part of its existence. Regardless, the Wurstküche has been around for a long time.

Crossing back over the Stone Bridge, I observed some sunbathers relaxing in the grassy area on the Stadtamhof side, as well as people taking a dip in the river there. This locale turned out to be a park with the formidable name of Naherholungsgebiet Steinerne Brücke, “Local Recreation Area Stone Bridge.” Lacking a sandy beach, the city of Regensburg instead provided this pleasant grassy area for sunbathers and picnickers, pleasantly shielded by wooded Wöhrde Island from the traffic on the main branch of the Danube.

By this time I was quite worn out and ready to board the bus back to Vilshoven – I think I slept most of the way. Back on the Monarch Queen, we had some festivities to celebrate our last night on the ship, but I stole some time to take a few last pictures of the river as well as some telephoto shots of the town of Vilshofen from the top deck of the ship. As I was thus engaged, a pair of lovely white swans swam up near the riverbank next to the Monarch Queen. It was a delightful conclusion to a memorable day and a fairytale cruise on the Danube.