The Mezquita of Córdoba contains a traditional cruciform cathedral inside a Muslim mosque. How that came to be is a story worth telling.

By 1523 Carlos I was both King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor as Charles V. The Bishop of Córdoba (and later Inquisitor General as well as Cardinal), Alonso Manrique de Lara, wanted to build a new cathedral in Renaissance style. The Córdoba city council vehemently opposed this idea. The bishop appealed to Charles V, who, being a devout Catholic, gave him the go-ahead. Later, upon seeing the (unfinished) result in 1526, Charles V is supposed to have said something like “You have built what you or anyone else might have built anywhere; to do so you have destroyed something that was unique in the world.” I very much doubt whether Charles V said anything of the sort; he was responsible for demolishing a Moorish palace in the Alhambra in order to build a Renaissance residence for himself, so it seems unlikely that the Córdoba project vexed his esthetic sensibilities. But somebody said something like it, and I agree: the cathedral, occupying the central section of the mosque, is a worthy endeavor, considered one of the best in Spain, but one can see similar achievements in Seville or Burgos, and I would rather have seen the Mezquita in its pre-1523 state. In any case Charles V did not see the final result, since it was not completed in his lifetime.

On the other hand, it has been observed that had the cathedral not been built inside the mosque, as opposed to another location in the city, the mosque might not have survived at all; making it a Christian holy place ensured its sanctity.

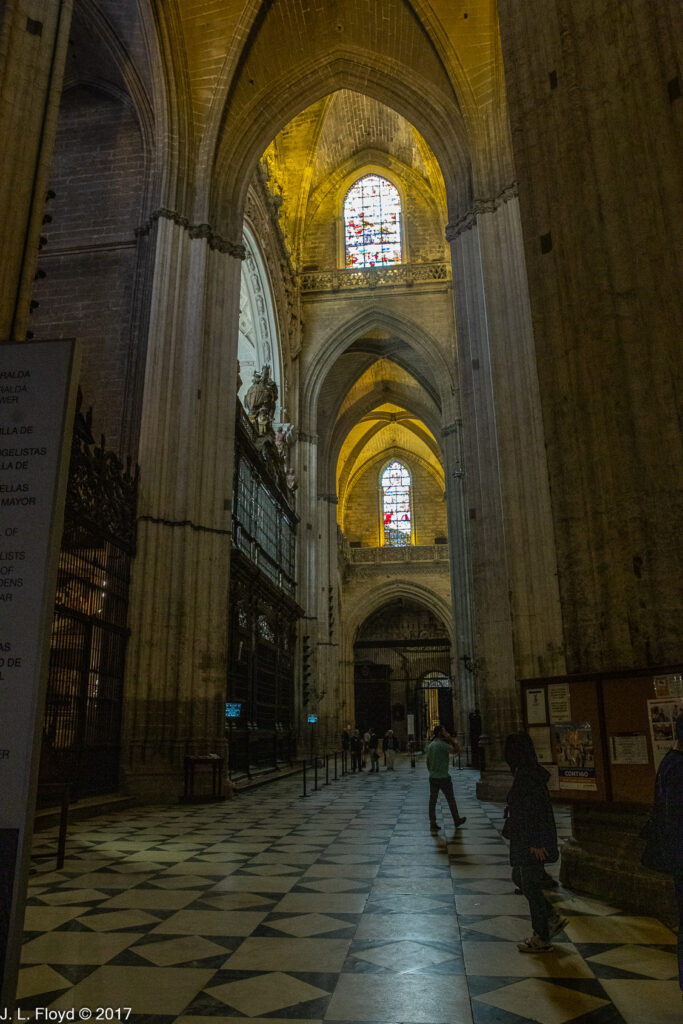

In any case, the architect chosen to design the cathedral, Hernán Ruiz, fortunately had a high regard for Moorish architecture and displayed considerable sensitivity in preserving as much of the mosque as possible while fulfilling the prescriptions of the sponsors. He started the construction of the nave, but died in 1547, leaving his son, also named Hernán Ruiz, to continue his work. Hernán Ruiz II built the walls of the transept, but he died in 1569, leaving the project still unfinished, and it was then entrusted to Juan de Ochoa, who completed the ceilings of the nave and transept in 1607. But even this was not the end result; the Capilla Mayor still needed an altarpiece, which was begun in 1618, and finished in 1653. During this prolonged period of construction, artistic fashions evolved considerably, so that the cathedral incorporated several different architectural styles – Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque.

As a consequence of all these changes, the number of columns in the Mezquita was reduced from 1250 to a mere 856.

The cruciform cathedral has four main sections: the Capilla Mayor, which contains the High Altar; the Choir; the Transept, which forms the arms of the cross and contains the Crucero, or Crossing, separating the Capilla Mayor from the Choir; and the Trascoro, or retro-choir, a space at the back of the choir for the clergy and altar-ministrants to assemble.

We first encountered the cathedral by way of the Trascoro. The wall separating it from the choir is decorated with a set of columns framing two doors presumably connecting to the choir, presided over by a relief nestled in an upper alcove depicting St. Peter seated in a chair at the heavenly gates.

The orientation of Ruiz father and son was primarily Gothic, and this is reflected in the high vaults and walls of the cathedral. But it was Ochoa who completed the choir ceiling and the dome over the transept, and he was a Mannerist. I won’t attempt to explain Mannerism here, but in short, it was an outgrowth of Renaissance styles characterized by elongated proportions, highly stylized poses, and lack of clear perspective. To me, Ochoa’s ceilings appear simply as Renaissance art.

Yet the final appearance of the choir section is neither Gothic nor Renaissance, because it was only finished in the 1750s, when the Baroque sculptor Pedro Duque Cornejo installed 53 intricately decorated choir stalls which he had carved in mahogany wood. The west end of the choir is dominated by an episcopal throne, also by Duque Cornejo, dated 1752, and designed like an altarpiece, with three aisles and a depiction of the Ascension of Christ into heaven on the upper vault, topped off by a statue of the archangel Rafael.

The altarpiece of the Capilla Mayor, begun in 1618, was not finished until 1653, and even then changes were made later. A Jesuit, Alonso de Matias, designed it in the Mannerist style, structuring it in three aisles separated by dual composite capital columns, and two levels above the base. Occupying the central bay of the altarpiece is a towering splendid Tabernacle, which displays the consecrated Host. Directly above the tabernacle is a painting of the Assumption of Mary, while the side bays are filled with canvases featuring martyrs of the Church, all by Antonio Palomino, a court painter from Madrid. Palomino received his commission for these paintings in 1713, when Europe was already well into the Baroque era, and they replaced originals which were also Baroque in style.

Just outside the Capilla Mayor, on either side of the transept, are two imposing Baroque pulpits carved in black marble, mahogany and bronze by a French sculptor, Michel Verdiguier, who completed them in 1779. They are dedicated to the writers of the Gospels: the one on the right, to Matthew and Mark, the one on the left to Luke and John.

Every proper cathedral has to have a sacristy or treasury, and the one in the Mezquita is located on its south side, in the Capilla de Santa Theresa, where we headed after viewing the Capilla Mayor. The Chapel of Saint Teresa was a late addition, having been founded in 1697 by the Bishop of Córdoba at the time, Cardinal Pedro de Salazar. He was a devotee of St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), the great Spanish mystic and religious reformer, and patron saint of those who suffer from headaches. Salazar intended it to be a funerary chapel for himself and his family, as well as a sacristy, and he is indeed buried there. He located the chapel, appropriately, in the same place where the treasury of the mosque had been centuries before.

The most striking of the many sacred objects displayed in the Treasury is the Processional Custody of Corpus Christi. This is a gold and silver monstrance, a container where the consecrated Host is displayed for veneration during ceremonial processions. It was the creation of two artists, one of whom, Enrique de Arfe (1475-1545), was of German origin (birth name Heinrich von Harff), but apparently worked all his professional life in Castile. He is credited with introducing Renaissance innovations in precious metalworking to Spain. In the seventeenth century the Spanish silversmith Bernabé García de los Reyes augmented Arfe’s work with a new base and other additions, completing the monstrance in its present form.

A number of other historically significant and precious gold and silver sacred objects were on display – processional crosses, reliquaries, scepters, etc. No less imposing were the paintings and sculptures in the Treasury. Almost all of them are products of the Baroque era, late 17th and early 18th century. There are eight statues of saints and church fathers by the celebrated sculptor José de Mora Exposito of Granada, placed between the arches of the chapel. And of course there had to be a sculpture of Saint Teresa of Avila, also by de Mora, which presides over the altarpiece of the chapel. I don’t have a photo of it, but a better one than I could have obtained may be seen here. She is depicted holding a book with a dove on her shoulder.

Two famous but anonymous paintings, located over the chapel doors, represent The Immaculate Conception and The Assumption of Mary. But I was more drawn to three canvases by Antonio Palomino illustrating scenes from the history of the city of Córdoba: The Martyrdom of Saint Acisclus and Saint Victoria, The appearance of Saint Raphael before Father Roelas, and The conquest of Cordoba by Fernando III the Saint. The last of these is the only one associated with a verifiable historical episode: it depicts the triumphant entrance of King Ferdinand (Fernando) III into Córdoba in 1536. We did not photograph it, but you may see it here. The other two deal with episodes which I would describe as legendary, but which Córdobans certainly believed to be true. The Appearance of St. Raphael to Father Roelas is the last of several occurrences in which the guardian angel of Córdoba is supposed to have revealed himself to local clerics to announce his divine appointment as custodian of the city. The Martyrdom canvas depicts an episode from 304 CE, during the persecutions of Diocletian, in which the Roman prefect of Córdoba had the youth Acisclus and his sister Victoria tortured and killed for refusing to abjure their Christian faith. They were later made patron saints of the city.

Before leaving the Treasury, I want to show a few items we observed there which were of less exalted character than the sacred objects pictured above, but which we found intriguing for one reason or another. I have not been able to find out much about these more mundane pieces, but they are worth presenting nonetheless.

The Treasury is situated next to the Mihrab, which I’ll deal with in the next post, where I conclude our visit to the Mezquita.